Middlemarch – George Eliot – 1871

The following is a compilation of discussions and reviews from the previous version of our website. We hope you enjoy these older deliberations. Just beware, there may be spoilers in here. To add your own review or remarks, please scroll down to the comment box. — ReadLit Team

J.B. Handelsman – The New Yorker, 1994

Posted by Lale on 25/4/2006, 11:28:11

I am reading George Eliot’s Middlemarch. I am at page 200. The second one-hundred pages were rough terrain. Middlemarch is just as encyclopedic as Romola, another George Eliot book of 800 pages.

Anyone else read this book?

Steven how are you doing on Middlemarch? Are you as angry as I am with Dorothea?

Lale

~

Posted by Steven on 25/4/2006, 13:44:43

: Steven how are you doing on Middlemarch? Are you as

: angry as I am with Dorothea?

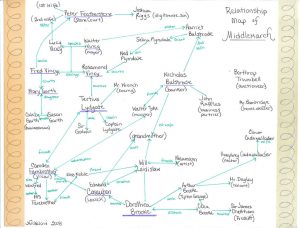

I’m at about page 330 (out of 800+). Parts of it are rather tough going because of cultural references from the 1820s, but the footnotes in the Penguin edition I’m reading are a help. There are a lot of characters to keep track of too, and the number keeps growing. But the book is well worth the effort.

Yes, Dorothea is self-righteous and puritanical. She marries Casaubon for the same reason she wears plain dresses and abstains from jewellery and curls – not because it’s what she loves, but to set herself above and apart from everyone else. I’m much fonder of Rosamond.

The passage at the beginning of Chapter XXIX that analyses Mr. Casaubon’s motives and feelings is very meaningful to me. Sometimes we take on the outward trappings of a thing, assuming that it will improve our outlook, only to find that we become more entrenched in the characteristics that we were trying to get away from. Casaubon marries Dorothea, assuming this will bring him help in his labours and domestic bliss. But he is, and remains, a sour, solitary old man. Marrying a beautiful young woman did not change the limitations of his personality; it only emphasized them, making him react by becoming even more bitter and withdrawn.

Steven

~

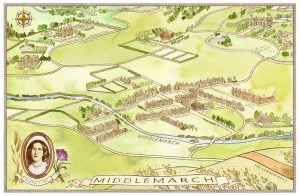

Caitlin Kuhwald – http://www.caitlinkuhwald.com/crown-publishing/

~

Posted by Lale on 26/4/2006, 9:56:46

Steven, I thought Dorothea’s story and the rest of the book seemed disconnected and almost like two different books. This suspicion was confirmed to be true when I read a George Eliot timeline. Look:

1869 – Begins writing ‘Middlemarch’ (the Featherstone – Vincy part) in August.

1870 – Puts aside ‘Middlemarch’ in despair, and in November begins a new story ‘Miss Brooke’ which develops rapidly.

1871 – Combines the two narratives early in the year to create the first section of Middlemarch, to be published in eight parts.

~

Posted by Steven on 26/4/2006, 11:11:05

: I thought Dorothea’s story and the rest of the

: book seemed disconnected and almost like two different

: books. This suspicion was confirmed to be true when I

: read a George Eliot timeline.

Fascinating! It makes you wonder how many other large novels were originally conceived as separate stories that the author decided at some point to merge into one. It would be easy to imagine War and Peace or Anna Karenina having begun this way. I can only stand in awe of someone who can conceptualize and execute a quality novel on the scale of these works, however they go about it.

Combining the two stories of Middlemarch really works in the historical sense because you have the parallel lives of the landed gentry and the urban mercantile class against the background of the Reform Act debate, which was a major shift of political power from the gentry to the urban classes.

I hadn’t known about the Reform Act before now, but there’s a tie to “A Sentimental Education” which we read last year. The Reform Act of 1832 did for England much of what the Revolution of 1848 did for France by empowering the middle class at the expense of the landed gentry, so the political background of the two novels is very similar.

: I started to make a list/table of all the characters

: and their relationships to one another. Once I finish

: all the characters up until Book III (that’s where I’m

: at) I will post it here and we can finish it together.

Good idea. I’ve often wanted to do this as I read a book of this type, but I do much of my reading while commuting on the bus, so it wouldn’t be practical.

It would also be helpful to list the names of the estates next to the people who owned them (e.g. Tipton Grange – The Brooke Family; Stone Court – Peter Featherstone), since it’s easy to lose track.

~

Posted by Paul L on 30/4/2006, 16:49:26

I read Middlemarch on a trip to Ireland a bit ago. I enjoyed it- the relationships were interesting to me. Of course, Casaubon was the most interesting character to me, for a number of reasons- but mainly because I’m a sucker for both curmudgeons and academics- they amuse me. I sympathize with Dorothea- to me, a lot of what she does that I disagree with I can write off to idealistic naivety.

~

Posted by Guillermo Maynez on 21/5/2006, 11:20:04

How’s “Middlemarch” going? Sounds like one book I’d like to read. I read “The Mill by the Floss” many years ago and I liked it.

~

Posted by Rizwan on 23/5/2006, 18:39:46

As for Eliot, I’m the opposite of you. I read “Middlemarch” a few years ago and enjoyed it very much. One of the most “intellectually accomplished” novels of the 19th century. Never read “The Mill on the Floss,” however, though I’ve wanted to ever since I read that Proust studied (not just read, but studied) her evocation of childhood in that book.

~

Posted by Lale on 25/5/2006, 17:59:56

I finished it!

Then I read the introduction by Felicia Bonaparte (32 pages).

Meanwhile here is something cute from the book:

“Mr. Lydgate had the medical accomplishment of looking perfectly grave whatever nonsense was talked to him.”

~

Posted by Steven on 25/5/2006, 19:14:35

Maybe I was just in a receptive mood, but I found the closing chapters – the encounters between Dorothea and Rosamond and, later, between Dorothea and Will – to be the most emotionally intense passages I have read in a long time. The way she revealed their feelings through body language more than dialogue, always subtle and absolutely believable, was just fantastic.

I hope you also found it to be a great book. The two plot lines of Dorothea and Lydgate come together so well at the end that it’s hard to imagine their working as well as separate novels the way she originally intended.

Posted by Rizwan on 26/5/2006, 11:36:56

I wrote this very broad little blurb in 2003 on my list of books read. Since then, I’ve forgotten a lot about the book, so I’m not exactly sure what it means any more. Don’t think it really goes to the heart of the book, but for what it’s worth:

Dorothea and Rosamond were women ahead of their time. Or were they? Surely they weren’t alone. (see Eliot, George). Great book, very intellectual writer. On a personal level, perhaps I am nothing more than Lydgate. Or maybe I’m a combination of Lydgate and Mr. Casaubon, who is little more than a selfish and self-centered bore.

~

Posted by Lale on 26/5/2006, 14:35:32

: Dorothea and Rosamond were women ahead of their time.

: Or were they? Surely they weren’t alone. (see Eliot, George).

: Great book, very intellectual writer. On a

: personal level, perhaps I am nothing more than

: Lydgate. Or maybe I’m a combination of Lydgate and Mr.

: Casaubon, who is little more than a selfish and

: self-centered bore.

I also thought that I was a little bit like Casaubon. I, too, start huge projects with not well-defined boundaries, and then I am overwhelmed and cannot finish.

George Eliot herself suffered from “too much research” as well. When she was researching for her Romola she risked the failure of the entire project because she simply couldn’t start writing, she was incessantly researching the 15th century Florence and Savonarola. From Andrew Brown’s introduction:

“As things turned out, the more she studied the more convinced she became that she was not yet ready to start writing. Her trepidation at attempting so different a work from her previous novels paralysed her creative faculties and, as if by way of compensation, the relentless acquisition of background details became an end in itself, almost an obsession. Instead of writing a novel, Lewes reflected gloomily, she was compiling an encyclopaedia, and making herself ill with worry in the process. George Eliot suffered attacks of diffidence during the composition of each of her novels, but never more acutely than in the case of Romola. […] Her journal for the period records a depressing succession of headaches, nausea, and nervous debility. For days on end she was too sick to work, and on a number of occasions she considered abandoning the project altogether.”

But she didn’t abandon the project. And, unlike her character Mr. Casaubon, she didn’t die before finishing it either. But she said, later on, “I began it a young woman, – I finished it an old woman.”

The other day I saw a very nice quote in the paper, I forgot who said it and how he said it exactly but it was something like this: Success means (etymologically, literally) following through. That was the gist of it. To succeed you have to finish it, follow it through. You will never achieve success if you leave it incomplete.

Lale

ps: Lewes is George Henry Lewes whom Eliot meets in 1852. Lewes is married but nevertheless they become companions until Lewes’ death in 1878.

~

Posted by Rizwan on 26/5/2006, 15:25:30

Agreed: follow-through is everything! (or most everything). I definitely plead guilty on this one. That must have been what I was referring to when I compared myself to Casaubon.

~

Posted by Steven on 26/5/2006, 17:23:16

: I also thought that I was a little bit like Casaubon,

: in that I also start huge projects whose boundaries

: are not well defined and then I am overwhelmed and

: cannot finish.

Make that three of us. Some of us never grow out of the childhood urge to dig a hole to China in the back yard.

One of the many things I like about Middlemarch is that the characters are realistic and neither perfectly good or entirely bad (with the minor exception of Raffles). Dorothea is almost too good to be true, especially at the end, but she is a bit self-righteous. At the other end of the spectrum, even Bulstrode has his good points.

More importantly, the “goodness” and “badness” of the characters depends on how they interact with one-another, both in how they are changed and how they are perceived. Lydgate thinks he can be an island unto himself, but his life is shaped by Rosamond, Bulstrode and Dorothea’s influences.

Another aspect of the novel that I liked was the sense that it was part of a real place and time. The Reform Law debate, the mention of various religious issues, references to literature that the characters were reading – all these things give Middlemarch a point of reference in the real world and give us a bit of insight into that period of history.

~

Posted by Steven on 26/5/2006, 23:22:52

Another observation on Middlemarch that just came to mind:

Note how Eliot’s style changes during the course of this large novel. In the beginning, she interjects herself into the story, usually in a light-hearted vein. She uses the first person regularly. At one point she even pauses to compare her style to Henry Fielding’s.

All of this is absent by at least the last third of the book, if not earlier. The story takes over. We sense how the characters feel from what they say and do. The author no longer stops to tell us what she thinks about them.

Whether this change was deliberate or not is something I certainly can’t say, but the effect is that the wit and reflection of the first part of the book are gradually replaced by a more serious, intimate and passionate style.

~

Posted by Lale on 27/5/2006, 10:35:35

: Note how Eliot’s style changes during the course of

: this large novel. In the beginning, she interjects

: herself into the story, usually in a light-hearted

: …

: All of this is absent by at least the last third of

: the book, if not earlier.

Not at the very beginning either. The author was not present up until Dorothea got married and left for Rome. She (Eliot) came in for the first time in Rome when she was explaining why Dorothea was crying. Or at least that was the first time when I noticed her intervening, I was surprised, I said to myself “she changed her mind about the style of the novel”.

~

Reform Bill – Posted by Lale on 27/5/2006, 11:54:18

: Another aspect of the novel that I liked was the sense

: that it was part of a real place and time. The Reform

: Law debate

The Reform Bill was confusing to me. On page 763, we are informed that the Lords had just thrown out the reform bill. Then, I was read the introduction which speaks as if the bill had passed.

As it turns out (based on what I understand from the internet), it had first passed and then thrown out (within days).

~

Posted by Lale on 26/5/2006, 13:28:31

I liked the book. But I couldn’t like Dorothea. Her marriage to Casaubon was doomed from the get-go, and we could see it, why couldn’t she? Had she absolutely no notion of “chemistry” between a man and a woman?

Then, I was a little tired of her constant whining such as “I have so much money, I don’t know what to do with it.”

What happened to Celia? She was a smart girl before marrying to Sir James Chettam. After the marriage, she became downright silly.

I liked the fact that all the characters were flawed, and therefore real-like. Unlike in Dickens’ books, nobody is always good, extremely good, or evil, very very evil. No such exaggerated characters in Middlemarch. I also enjoyed the inner thoughts of every character. Eliot gives us their psychology, places everyone within the context of their own emotions, fears, personality traits, likes and dislikes.

There were definitely some weak points in the book, there were some underdeveloped sub-plots which either didn’t go anywhere or ended in an anti-climax. For instance, the dying old man, the uncle Mr. Featherstone’s will… Much was made about it, there was a long and high build-up and then poof! Neither the presence of multiple wills nor the actual leaving everything to his out-of-wedlock son (whom he had never did anything for while alive) didn’t deliver the surprise or the punch we were set up for. The son sold the place and left never to be heard of again. There wasn’t an earth-shattering difference between the multiple wills anyway.

~

Posted by Rizwan on 26/5/2006, 15:20:32

You’re right, Lale. Dickens’ characters are often merely caricatures, whereas Eliot, at least in Middlemarch, puts a lot more flesh on them, so to speak.

But speaking of Dickens: to answer your other question, he is loaded with instances of characters suffering in debtor’s prison. I think Mr. Pickwick, for instance, and surely others. And then there is an entire novel he devoted to this subject: “Little Dorrit.” I had a conversation with my boss about Dickens a while back, and he told me “Little Dorrit” was by far his favorite Dickens novel.

~

Posted by Lale on 27/5/2006, 12:10:44

Did anyone understand what the “key to all mythologies” was all about?

From the introduction (Felicia Bonaparte):

[Eliot] was one of the first to recognize that the crisis of faith had turned all the creeds into mythologies and that in those collected myths might be gathered the universal and eternal truths of religion free of their theological forms. The gathering itself was important, for it helped to identify, if only by the repetition of perspectives and concerns in the mythologies of the world, what the human mind had always imagined as its possibilities and to distinguish these from ideals merely transient and parochial. Freed, moreover, of their creeds, these myths revealed not only the essence of the moral beliefs of the species but the universal truths of the whole of human existence. Casaubon, thus, is not mistaken, despite the mirth his enterprise has provided the novel’s readers, to undertake his ambitious Key. The key to all the world’s mythologies was what Eliot herself was looking for. His error was to be searching for it in the archives of the Vatican (p. 180). In the modern world mythology has its natural home in art.

~

Posted by Steven on 27/5/2006, 19:13:43

: Did anyone understand what the “key to all

: mythologies” was all about?

My interpretation may be rather simplistic, but it is that Casaubon was attempting to prove that all religions derived from a common source – Darwinian evolution applied to belief systems. And given that he was very closed-minded and self-centered, he no doubt believed that his Christian beliefs represented the root and the purest form of religion, of which all other faiths were just mutated offshoots.

I can’t dispute what Ms. Bonaparte says about George Eliot’s own pursuit of a universal set of values – though I don’t think this comes across just from reading Middlemarch – but it certainly wouldn’t have been Casaubon’s motivation. He wasn’t out to find his place in the world, but to prove that he was at its center.

~

Posted by guillermo maynez on 8/9/2016, 10:34:30

I’m done with Middlemarch. It really is a mangificent novel, a grandiose fresco of provincial society in an age of change (the Industrial Revolution, the Reform Bill of 1832 which expanded the electoral franchise and redesigned electoral districts). The characters are truly complex and three-dimensional, and Eliot’s style is worth comparing with her contemporary, Dickens.

~

Posted by Sterling on 18/9/2016, 8:57:21

Guillermo, I thought that Middlemarch was a deeply impressive novel when I read it quite some time ago. (The edition on my shelf was published in 1985.) As I recall, I thought it actually more carefully structured and possibly even better written than Dickens. It seems to me that I thought it lacked his expansiveness, humor, and vitality. But it’s not “baggy,” the way many of Dickens’ lesser novels are. Middlemarch should, I suppose, be compared to the very best of Dickens, e.g., Bleak House. Dickens still wins by a bit to my taste. I really can’t imagine Eliot killing off a character by spontaneous combustion!

~

Posted by Joffre on 18/9/2016, 11:04:42

Middlemarch is massively impressive. I am very tempted to say it’s far better than anything by Dickens, and yet, I find three or four Dickens novels more enjoyable to read.

~

Posted by Sterling on 18/9/2016, 16:54:00

Middlemarch is a magnificent novel, but somehow it’s not very lovable. Maybe it’s too lacking in humor. (That may be unfair. It’s a long time since I read it.)

~

Your comments are very welcome. Please sign in and use the contribute box below to write a review or to add your comments. You may also enjoy our Talk Literature page for active discussions.