The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time – Mark Haddon

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time – Mark Haddon – 2003

Posted by Lale on 13/5/2004, 11:03:45

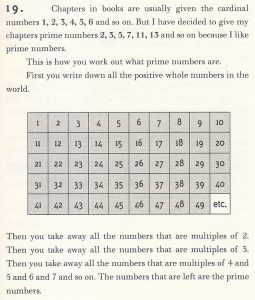

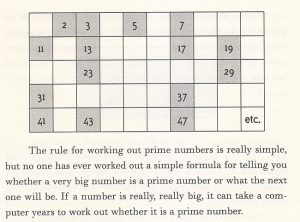

What is wrong with this picture? What happened to 1 (one, uno, eins, unus) ?

Posted by moana on 13/5/2004, 11:56:23

One isn’t a prime number, it’s more of a superprime. The reason most mathematicians don’t include one as a prime is because when you’re defining things in terms of prime factorization, you don’t want to have to deal with multiples of one – a common definition is that there is only one way to do a prime factorization of any number, like

12 = 3 * 2^2

If you let one be a prime, there wouldn’t be a unique factorization, you could have

12 = 3 * 1^n * 2^2 for any n, and it just confuses things.

As for this kid, I don’t know how he knows that it helps things to not consider one a prime. *shrug*

~

Posted by Lale on 13/5/2004, 12:02:15

Nice explanation. But I’ve never heard of it before. We were told: “1 is a prime number.” Period.

By definition (“a number which can only be divided by 1 and by itself”), 1 fits the bill. Also, by the definition given in the book (“a number that is not a multiple of 2, that is not a multiple of 3, that is not a multiple of 4 …”) 1 is still a prime. I felt that the author was defeating his own definition.

Lale

Posted by Lale on 16/5/2004, 9:59:42

Moana,

What do you think of the doors with the goats/car behind them story?

The formula that explains the 2/3rds answer didn’t speak to me, so I happily moved on to the picture/flowchart explaination, but that is not complete and doesn’t prove anything. It doesn’t have all the possibilities.

So, I am still left with my ordinary person’s answer which is 50-50.

By the way, friends, I finished the book and I sense that most of you did as well. Did you? If Len is ready maybe we can start to talk about it?

Lale

Posted by moana on 16/5/2004, 11:38:52

The Monty Hall problem of whether to switch or stay was part of my introduction to programming class last year. We had to code the actual game and let the user switch or stay. The outcome was always a 2/3 percentage of winning if the user switched. So I’m very convinced, even empirically.

Mathematically, the reason the odds are better for switching is because Monty Hall, when opening the first door before you get a chance to stay or switch, ALWAYS OPENS A DOOR WITH A GOAT. If that choice were random, then the odds would be 50/50. However, eliminating one of those goats makes the odds a sight better when you switch.

What are the other possibilities? Monty Hall can’t open a door with a car behind it; then the game wouldn’t be any fun. “Stay or switch? Which way do you want to lose?”

😉

Anyway, it’s a hard one to understand, because it’s so counterintuitive. There are plenty of programs that explain the answer a bit more thoroughly; search google for “monty hall problem” and you’ll get a bunch of better explanations.

Posted by Meg on 13/5/2004, 20:27:28

“Prime numbers are what is left when you have taken all the patterns away. I think prime numbers are like life. They are very logical but you could never work out the rules, even if you spent all your time thinking about them”

Compare to Tom Stoppard’s “Arcadia” (one of my all-time favorite plays…). It’s not a perfect comparison, but somewhat lovely all the same. And it gave me a chance to revisit this lovely play.

In case anyone has read Stoppard before — he writes like Shakespeare. Not as in he writes the same way Shakespeare does, but to the same purpose: his texts lived best when spoken aloud. So, maybe have fun reading this little present out loud…

cheers.

meg

***

“Valentine: The unpredictable and the predetermined unfold together to make everything the way it is. It’s how nature creates itself, on every scale, the snowflake and the snowstorm. It makes me so happy. To be at the beginning again, knowing almost nothing. People were talking about the end of physics. Relativity and quantum looked as if they were going to clean out the whole problem between them. A theory of everything. But they only explain the very big and the very small. The universe, the elementary particles. The ordinary-sized stuff which is our lives, the things people write poetry about — clouds — daffodils — waterfalls — and what happens in a cup of coffee when the cream goes it — these things are full of mystery, as mysterious to us as the heavens were to the Greeks. We’re better at predicting events at the edge of the galaxy or inside the nucleus of an atom than whether it’ll rain on auntie’s garden party three Sundays from now. Because the problem turns out to be different. We can’t even predict the next drip from a dripping tap when it gets irregular. Each drip sets up the conditions for the next, the smallest variation blows prediction apart, and the weather is unpredictable the same way, will always be unpredictable. When you push the numbers through the computer you can see it on the screen. The future is disorder. A door like this has cracked open five or six times since we got up on our hind legs. it’s the best possible time to be alive, when almost everything you thought you knew is wrong.”

Posted by Lale on 14/5/2004, 10:29:07

This passage is lovely. I had never thought of it: “But they only explain the very big and the very small.”

Thanks for typing that up for us.

I only know Tom Stoppard from “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead”, which I never saw as a play but watched many many times as a movie.

Lale

Posted by moana on 15/5/2004, 11:08:19

Tom Stoppard is the writer of the screenplay for Shakespeare in Love, which is why it’s such a great movie! 🙂

~

Posted by the bunyip on 25/5/2004, 19:21:20

G’day, People,

If I’m allowed to do this sort of thing, my comments on Curious Incident can be found here:

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/cm/member-reviews/-/AJDYDG7YZY9QL/

cm_aya_av.rev_prev-61/103-4036272-3751036?start-at=61&

This book can’t be too highly praised. Our view of what is “normal” has been conditioned by immense forces – of which “literature” stands tall. It should be standing in the dock.

A generation of studies on mind/brain has been sweeping away many preconceived notions about ourselves. This book offers many insights challenging our established views by exposing the mind of someone most of us would either ignore or avoid. Christopher is one of those “strange children” we’ve all encountered – likely in our early schooling. We were supposed to have made progress in relocating “strange” people from asylums and into “special schools”. According to Haddon, that was a minimal step.

This isn’t a “comforting” book, nor is it meant to be. The contrast with the Fitzgerald couldn’t be more striking. Ask yourself, who would you rather wish to call a friend, Dick Diver or Christopher?

the bunyip

Posted by Lale on 25/5/2004, 22:33:34

: be more striking. Ask yourself, who would you rather

: wish to call a friend, Dick Diver or Christopher?

Good question, Bunyip.

But you know, the answer is not always “Christopher”. I am sure sometimes Christopher’s mother wished that she had a Dick Diver as a child instead of Christopher. At the end, we know that she wouldn’t trade-in Christopher for all the Dick Divers or all the gold in the world but she was darned tempted. She even attempted.

It is not easy.

Lale

Posted by Anna van Gelderen on 26/5/2004

: This isn’t a “comforting” book, nor is it

: meant to be. The contrast with the Fitzgerald couldn’t

: be more striking.

You mean that Tender Is the Night is a cosy, comforting book?! You must have read an entirely version.I found nothing comforting in reading about vapid, lost, mentally disturbed people with empty lives.

: Ask yourself, who would you rather

: wish to call a friend, Dick Diver or Christopher?

What does that have to do with anything? You seem to imply that a book is better if its protagonist is more likeable. You seem to confuse the enjoyability of a novel and the likeability of its characters with literary quality. According to that view Thackeray’s Vanity Fair can’t be much good, for Becky Sharpe is nothing but a scheming, manipulative little bithc and Crime and Punishment is downright trash, for who in his right mind could like Raskolnikov? Danielle Steele’s heroines are probably perfectly loveable (I can’t be sure, because I have never read any of her bestsellers), but that doesn’t make her books great works of art.

A while ago we read Patrick White’s The Vivisector. The main character to me was so repulsive that I could not continue with the book. I hated it. But I would never say that Patrick White is not a good writer, or that his novels are second rate. On the contrary, Patrick White is excellent, and so is The Vivisector – I just got thoroughly depressed reading it and I don’t want to read another of his books. But that’s not because he is a lousy writer.

Posted by the bunyip on 26/5/2004, 18:14:35

You’re quite right, Anna. It’s too easy to judge a book by the people in it. I liked Elizabeth Hay’s Student of Weather, but found none of the characters people i would associate with.

In the case of Tender, those people were beyond redemption, yet represented a looked-up to element of American society. Their future was behind them – they lacked values and purpose. I would rather try to make friends with Christopher than Diver.

Christopher’s story is a bit different. Few of us would be comfortable in his presence. So what do we do about that? At the beginning of the 20th Century, there was a group of writers known as The Muckrakers who urged a change in how society viewed business practices. Curious is related to that movement. Christopher asks “what is ‘special needs’? He recognises he’s been shunted away from the rest of society in his schooling, yet has ambitions that will not permit him to stay segregated. In fact, his abilities are likely to be overlooked if he’s allowed to remain ignored.

This book should be a landmark in how we feel about others.

Fitzgerald, along with most literature, views behaviour from the outside. Haddon has managed to “get inside” the head of a special human being and describe it for us. That’s a significant accomplishment. We need to take the next step in beginning to learn how to deal with such minds. Keeping them sequestered is clearly not the answer.

the bunyip

~

Posted by Anna van Gelderen on 26/5/2004, 1:46:51

I do agree with your assesment there that “Haddon provides a revelation into autistic minds no clinical study can match.”

That’s the power of fiction, something that can hardly be explained to technocrats who dismiss literature as irrelevant and “just” entertainment.

Anna

Posted by the bunyip on 26/5/2004, 18:29:30

Agreed wholeheartedly, [here it comes!] BUT . . . how much “literature” can you truly credit with that accomplishment? I’ve read many things i liked for various reasons, but laid aside without regret, or intend to re-read, such as Tender. I would never reread that book.

Unlike Curious, Tender is a story of time and place. These people are of their age. There may be resemblances in other times and places, but American Nihilism is long extinct. The current situation may create a new version, but it will be for now, not drawn forward from then.

stephen

Posted by len. on 27/5/2004, 14:02:30

What I got out of “The Curious Incident …” was less about insights into Christopher than insights into the rest of us “normal” people. One of the things that Haddon’s remarkable depiction of Christopher’s worldview makes strikingly clear is how arbitrary and ritualistic much social convention is. The ritual performance of these group behavioural ticks often determines our membership in the group, and Christopher is an outsider as much because of his failure to master these ritual gestures as his being “difficult”.

What’s more, that mastery often entails forms of response that make no sense to Christopher, because they actually make no sense other than as ritual stimulus/response. When a stranger or mere acquaintance asks you “How are you”, they expect the ritual “Fine, how are you”, not a truthful answer. Giving a truthful answer, especially at length, will almost certainly become awkward. The truth is, they don’t really care how you are, nor do they really want to know.

Similarly, Christopher’s confusion about many idiomatic expressions bespeaks their absurdity. They make sense to us not because they literally make sense, but because we have learned the more or less arbitrary mapping to their social meaning.

These ritual conventions apparently evolved to help us distinguish group members from (potentially threatening) outsiders, and as such they provide us with some degree of comfort through familiarity. There is a compelling irony in the fact that their true meaninglessness denies Christopher, terrified by the unfamiliar and for whom they are opaque, that comfort and sense of belonging.

len.

~

Posted by the bunyip on 27/5/2004, 19:33:37

Good on yer, Len!

A first-class analysis of Haddon’s effort to educate the comfortable. Haddon has confronted us with a true conundrum – how do we shed our existing mind-sets? Others have tried, but never in this particular realm.

Thank you for that . . .

the bunyip

~

Posted by Lale on 1/6/2004, 8:41:50

: stimulus/response. When a stranger or mere

: acquaintance asks you “How are you”, they

: expect the ritual “Fine, how are you”, not a

: truthful answer. Giving a truthful answer, especially

: at length, will almost certainly become awkward. The

: truth is, they don’t really care how you are, nor do

: they really want to know.

Is there a solution to this?

Most people are not happy with this habit but nobody can come up with an alternative. I agree that there has to be an acknowledgement, so I am comfortable with good morning/bonjour all around but I think it has to stop after that.

In North America, all sales people are trained to say “How are you doin’ today?” I have a niece in retail and she tells me that there are many random checks on this and if the sales people don’t say that to a customer who walks in (or a company spy disguised as a customer) then they would get a warning. So, if you are walking in a mall and going in and out of stores, you are confronted with “hi, how are you doin’ today” many many times.

It is worse with acquaintances. Granted, some acquaintances are really nosey and gossipy, so they do want to know how you are today, if you are upset for any reason or if anyone in your family is sick or if there are financial or domestic problems. And some people do want to talk about these things. So, when there is a match, that’s good.

But most people don’t want to know and don’t want to tell. So, they stick to useless howareyou/Iamfine routine.

: Similarly, Christopher’s confusion about many idiomatic

: expressions bespeaks their absurdity. They make sense

: to us not because they literally make sense, but

: because we have learned the more or less arbitrary

: mapping to their social meaning.

Language is arbitrary. Verb conjugations are arbitrary. Pronunciation is arbitrary. Everything is arbitrary. Christopher was lucky to be very intelligent. He has to memorize the idiomatic expressions just like he learned irregular verbs.

I am too amazed by the idiomatic expressions, especially when I encounter one I have never heard before. But once you learn them, you can’t talk without them.

My favourite character in the book was Siobhan. Either by education or by disposition (possibly by both), she knew how to explain things to Christopher, and when she couldn’t she was still able to leave him with something, she never added onto to the confusion.

Lale

~

Posted by len. on 1/6/2004, 9:06:29

Lale replies:

>Is there a solution to this?

No. Well, yes — be comfortable with being perceived as rude or “weird”.

>I don’t do these so I am considered “rude”. I don’t understand it. Rude by what standards?

Theirs.

>Phony, fake chatter rudeness?

Exactly my point.

>Language is arbitrary. Verb conjugations are arbitrary. Pronunciation is arbitrary.

Yes, but arbitrary (but for the exceptions) in a systematic way. If these empty gestures were systematic, Christopher would have had little trouble mastering them.

>Everything is arbitrary.

Watch out, you’re treading perilously close to postmodernism (which I first mistyped as postmerdenism — nice Freudian slip).

>My favourite character in the book was Siobhan.

I don’t think it was that she was smart. She had experience dealing with Christopher and children like him, and she learned from that experience. It’s that learning and her thoughtful use of it that distinguished her.

>Either by education or by disposition (possibly by both) she knew how to explain things to Christopher

Knowing how to explain things well, to anyone, is indeed a special skill.

len.

Haddon’s Title : A Forgotten Clue

Posted by Pierre Pigot on 1/6/2004, 9:22:07

Sometimes, parallel readings can lead to wonderful discoveries. The very day I bought my copy of Mark Haddon’s heartmoving book (of which I’ll speak later), I was travelling through my omnibus edition of Sherlock Holmes’ adventures, when suddenly my eyes caught this ring-a-bell dialogue between the detective and his faithful Dr. Watson, in the short story called “Silver Blaze” (the name of a stolen race horse):

“Is there any point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

“To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

“The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

“That was the curious incident”, remarked Sherlock Holmes.”

(cf. The Penguin Complete Sherlock Holmes, p.347)

This dog wasn’t called Wellington, of course ; but I wonder how many so-called serious critics in New York, London or elsewhere, were incited by the young Christopher’s admiration to reread Conan Doyle’s victorian mysteries.

P.P.

~

Posted by the bunyip on 8/6/2004, 13:32:14

There are a couple of interviews with Haddon out there after his Whitbread that noted that point. And none of the pre-Whitbread critics twigged to it.

the bunyip