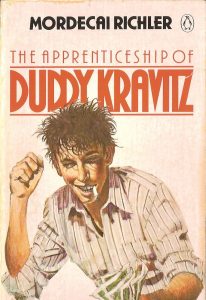

The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz – Mordecai Richler – 1959

The following is a compilation of discussions and reviews from the previous version of our website. We hope you enjoy these older deliberations. Just beware, there are spoilers in here.

ReadLit Team

Posted by Lale on 17/9/2001, 1:16:25

“A man without land is nobody.”

I liked this book enormously. However, I am surprised that some of the critics have used the word “funny” for this book. It is not a funny book. Dark humour is not the same as funny. There were moments of truly hilarious moments, for sure, such as the excerpts from the magazine, The Crusader. But in general it is a sad story.

Nobody got off clean. Nobody was one hundred percent dirty either. There were times when you *had* to sympathize with Duddy. How he longed for love of the members of his family. How he kept on asking about his mother, “did she like me?”. How he cuddled up to Lenny during the night they spent in Toronto. And how he was pushed away.

Anatomy is the big killer, you know.

Posted by Dave on 17/9/2001, 4:22:37

Yes, anatomy is definitely the big killer! We eat bread and it comes out toasted!

I also tended to read this book at breakneck speed… it seemed that once I started it I found it difficult to put aside for too long. I am still fascinated by Duddy’s “apprenticeship”. He is one of the most clearly developed characters I’ve ever read about, and his ruthlessness reminds me of Steerpike in Mervyn Peake’s trilogy entitled Ghormenghast (a totally different genre).

This is a story about ambition run amok! A precocious upstart trying to satiate his obsessive perception of “success”. Duddy’s particular obsession is, as Lale mentioned, this phrase that “a man without land is nobody”. I think Richler created a fascinating (realistic, albeit despicable) character here in Duddy. For me, Duddy was thoroughly despicable in the dictionary sense of “deserving to be despised”… he is the kind of person that, if I met him in real life, I would listen to (because HE would be the one doing the talking) for maybe three or four minutes maximum before my every internal instinct would be saying “run like hell”! A shyster! I agree with you Lale that Duddy at times evoked my sympathy… but then I read the NEXT page… and I wanted to strangle him again. Or… or LAUGH! I agree with you that this is “not a funny book” like Wodehouse or whatever… but seriously there were so many moments when I literally laughed out loud (an extremely rare occurrance for me when reading). For instance, the scene of the first screening of the Cohen movie produced by John Friar… truly hilarious as I picture Duddy literally trying to squirm himself into the upholstery of the chair! And just the average dialogue is funny… the Jewish banter. For instance, how many times do they say “A big deal” out of nowhere, or put the word “but” at the END of the sentence! “Jeez” it’s funny!

I wondered if Richler had a hard time keeping his protagonist so consistently despicable, really I found very few redeeming moments for the character of Duddy. I was especially appalled with his treatment of Yvette and Virgil… the two people who tried the hardest to be a part of his dream and see it fulfilled. His forging of Virgil’s cheque was for me the end of Duddy… it’s like he was already a car rolling downhill with no brakes, but that action of his sent him over the cliff. He has the cold audacity to take them all out for dinner afterwards… paying the bill with his guest’s own stolen money. Duddy the hero!

Richler does NOT leave things there though. In the final pages, we’re still not sure if Duddy has actually been re-united with his conscience, but we do know that it has at least given him a good kick in the rear end. In a very poignant scene, Duddy brings his family out to his ill-gotten LAND, and the very man who represents Duddy’s life-phrase about land, walks away from him in disgust. This is the old man, Duddy’s “zeyda” Simcha… and I think this is the most important moment in the book. Rather than pick out his own plot of land, he quietly hobbles off the hill and back to the car. His silence and subsequent tears convey his profound disappointment with Duddy, more than words ever could. Later, at Lou’s Bagel and Lox Bar, Duddy tries to literally RUN from the shame that Simcha’s rejection represents. He finds Yvette, and she too, utterly rejects him. Everyone has had enough of Duddy. Has he?

He gets back to the Bar and is confronted with the possibility that perhaps the only thing legendary about Duddy Kravitz are the stories that his father Max is already inventing. There can be only one thing more miserable than someone who reaches his goals by trampling on others, and that is to find out that after all the trampling that has gone on… you’re no success story after all! On the last page, Duddy can’t even afford bus fare! He becomes a nobody… with land!

Posted by Anna van Gelderen on 17/9/2001, 14:30:01

I am amazed that I never heard of this book before. It is excellent and deserves a wide public. Like Lale and Dave I enjoyed reading it very much.

Of course it is all about the American Dream gone rotten. Duddy Kravitz is the prototype of the Nobody who wants to be Somebody, thinking the only way to achieve this is by getting rich. In his case he interprets this as becoming a wealthy landowner, spurned on by his Grandfather’s saying that a man without land is nothing – which is an understandable sentiment for a recent immigrant from a part of the world where Jews were not allowed to own land.

Anyway, Duddy is the perfect embodiment of the idea that in America (including obviously Canada) anybody can become rich if only he wants it badly enough and works hard enough. And Duddy certainly works his fingers to the bones. You must give him that. But to succeed he must also be completely ruthless. And that Duddy is, too. From the beginning the author leaves us no doubt that Duddy is a despicable character: the way he torments his teachers leaves no room for sympathy whatsoever. This impression of Duddy as a ruthless egomaniac is later reaffirmed by the way he uses trusting and unselfish people like Yvette and Virgil.

Still, I also sometimes felt sorry for Duddy, which is maybe what Lale meant when she said this was a sad story, too. He has such bad examples and such bad advisors. His father is a weak man who has lost his selfrespect because he has taken up pimping to supplement his meagre earnings. He is therefore only too well aware that he is no role model for his younger son, instead of which he incites Duddy to become like the Boy Wonder, the local mobster. Mr Cohen, the successful scrap metal dealer, can hardly be called a wholesome influence either. Just as Duddy, shocked into a something of a consience by Virgil’s accident has tentatively come to realize that “Money isn’t everything” (p. 266) Mr Cohen gives him the following advice: “‘My attitude even to my oldest and dearest customer is this,’ he said, making a throat-cutting gesture. ‘If I thought he’d be good for half a cent more a ton I’d squeeze it out of him’.” (p. 267)

Near the end of the book, just for a minute, when his grandfather turns away from him at the site of his dreams, it still seems possible that Duddy may come to his senses. But then a waiter recognizes him as ‘the Mr Kravitz who just bought all that land’ and by the way Duddy smiles and triumphantly hugs his father we know that a change of heart for the better is now permanently out of the question.

And even then, I still felt sorry for this person who has allowed himself to be utterly corrupted by his relentless urge for recognition and love.

Posted by Lale on 20/9/2001, 11:29:06

One thing that was remarkable about Duddy was that he trusted Yvette. When someone asked him (I forgot who) “How can you hand over so much land to this girl ?”, Duddy didn’t skip a beat, he said “So? You have to trust someone.” Actually that happens to be my philosophy too. You have to trust someone, and then another someone and then another. You should trust a few someones. You can’t live your life suspecting everyone. I hate it when I hear people say “never trust anybody” or “I wouldn’t trust my own blood” What kind of a life that must be?

I am not saying that one should be naive. It is smart to be prudent. But it is also very very good to trust. Some of the people you trust will cheat you, you’ll get burned, that’s life, bad luck. In Ottawa, our house got broken into and every piece of jewellery that was ever given to me since I was born, 30 years worth of memories were stolen. That happened without me trusting the wrong person. You can get burned anywhere anytime.

Duddy, actually, trusted almost everyone, come to think of it. He trusted Yvette and Virgil, the old school friend Hersh and the intellectual types that showed up in his apartment. He didn’t even worry too much about Calder or Cohen. He pretty much trusted everyone. That was an interesting aspect of him.

Too bad he couldn’t live up to the confidence Virgil had in him.

Lale

Posted by Lale on 20/9/2001, 11:57:13

Chris, I was also amazed with how most of the book relied on dialogue. And very terse dialogue too. I found it brilliantly expressive with such economical use of words.

I never knew you could say so much with just “jeez”, “you don’t say” and “sure thing.”

That’s an interesting point, Duddy’s being such a trusting person. I agree that it is a positive character trait. This would grant Duddy at least one redeeming feature, unless you think it is just a manifestation of either supreme self-confidence or a complete lack of imagination. Personally I think that it also reflects a certain amount of naiveté, especially in the episode where he is set up with the roulette wheel. Every reader smells a rat from the start, but Duddy never really seems to suspect a scam. For a short while therefore we feel sorry for him (at least I did). This naiveté and his briefly being the underdog make him almost likeable. This makes him a more rounded character in my opinion.

Both the episode with the roulette wheel and his complete trust in Yvette also show that he is willing to take risks not everybody would have the guts to take. I don’t think I would ever trust another person with all the title deeds to my land (if I had any), but then I am a lawyer: I am being paid to be suspicious. By the way, can anybody tell me what “ver gerharget” means?

Posted by Dave on 23/9/2001, 7:57:18

Tonight I was over at a friend’s place… we made a real overly-dressed custom pizza and then turned on the tele to see what was there. To my utter enjoyment and surprise, a documentary of Mordecai Richler was just beginning! It was great… really old stuff, an interview with him that was done in 1970 for the National Film Board of Canada. He just seemed like such a cool guy, and he had many interesting things to say… at one point the camera panned to a pile of papers on a shelf, and then Mordecai explained that it was the manuscript of St. Urbain’s Horseman in its many stages of re-writing. (Seriously, it was three stacks of paper, each about 2 feet thick). He said that his best work is usually the stuff he doesn’t have to revise or re-write, which confirmed my sense of his writing as being “raw” (my word for it).

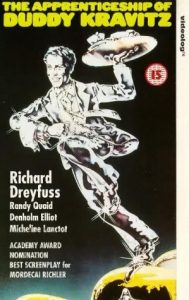

Anyway, the documentary was followed immediately by the movie of “The Apprenticeship Of Duddy Kravitz” starring Richard Dreyfuss as Duddy. It was very well done, and through this movie I got a new appreciation for Duddy… a sympathy even. The roulette scene is especially intense… Duddy is drenched in sweat as Irwin begins to win all the money from him. When he realizes he’s lost everything, Duddy runs outside and we see him actually vomiting, he’s so upset. In the movie we see that Duddy always MEANT well by the things he did. There is a scene where he screams at Yvette “Do you think I enjoyed stealing that money?” referring to his forging of Virgil’s cheque, and for the first time I realized that maybe he did it because he “honestly” felt he could help Virgil (and many others at the future Kravitzville Resort) better than these people could help themselves! Dreyfuss and the guy who played Max were superb, and I highly recommend the movie. It follows the storyline remarkably well. John Friar was a blast!

This movie was followed by another… Richler’s “Joshua Then and Now”… it was definitely Richler Night In Canada! I saw by the credits that he wrote the actual screenplays, which shows his versatility as an artist. A man of many talents who will be sorely missed. From our comments, I’m sure we will read more of his novels in the future, I know I intend to.

Posted by Lale on 23/9/2001, 12:46:19

Under normal circumstances nobody would sign their land over to someone else but if you were underage… He didn’t feel uneasy about it.

I found “ver derharget,” it means “drop dead.”(http://www.sbjf.org/sbjco/schmaltz/yiddish_phrases.htm)

The movie:

Richard Dreyfuss, Jack Warden, 1974.

Posted by Dave on 24/9/2001, 0:50:28

Dreyfuss is VERY VERY young in the movie. He’s like a kid but!

Richard Dreyfuss, Micheline Lanctot

Posted by Guillermo Maynez on 2/10/2001

I liked the book very much and I think Richler tells us a moral story without being lecturizing. I didn’t really like Duddy as a person – not my kind of a friend. Of course, in a very narrow sense, Duddy is a winner: he’s willing to do anything to fulfill his dreams. But, unfortunately, he’s got the wrong dreams. There’s no doubt Duddy was destined to make it in life, since he got the will and the drive to work hard, and he’s smart as hell. But he misses every chance to be happy and by the end the result is a disaster: yes, he has the land, but not a penny to pay a bus fare, much less develop his property. He’s lost the respect of his grandfather, he’s cheaply sold the antiques and library of his uncle Benjy, he is in heavy debt with no means to pay for it, but, worst of all, he’s lost a wonderful woman and a good friend.

He has stolen from Virgil and deeply hurts his feelings and those of Yvette. Contrary to what someone (I think Anna) said, I think nothing can justify what he did. Too many people -good and bad- fall victims of Duddy’s absolute lack of ethics. And his background serves us to understand, but never justify- his actions.

I am sure that the future has many setbacks coming for Duddy and I’m glad. I hope he is never able to develop his land and he has to start back from nothing and this time he realizes that a good woman like Yvette, a smart and gentle friend like Virgil, and the respect of his grandfather are something much more valuable than a piece of land. Shame on Duddy and greetings to the late Mordecai Richler for a very good novel about the American dream perverted and twisted.

Posted by Lale on 11/10/2001, 12:30:22

: he’s cheaply sold the antiques and library of his uncle Benjy

Oh, I had totally forgotten about that. He sold the library and the antique furniture. And he blamed Uncle Benjy for that. Benjy didn’t leave him any money, so he deserves his furniture to be sold. He had it coming to him. I thought Benjy’s leaving Duddy the house was going to be a turning point in Duddy’s life. Because, in fact, that was the most precious thing that Benjy could leave. It was his home built for his own children. But, no, Duddy needs cash. He can’t morgage the house so, off goes the rare books, rare furniture… Sold for only a fraction of their worth.

Posted by Suat on 11/10/2001, 23:47:37

I read Duddy Kravitz in three consecutive days. After the second day, I was almost ready to give full marks even though I was kind of annoyed with a couple of small nuisances.

Yes, they were cute, but I found the two insets much longer than they should be: the narration of his first video and Virgil’s newsletter. I got the joke after the first couple of pages and afterwards I was annoyed to be taken away from the story. I also found the usage of words “wha?” and “jeez” more numerous than necessary. These words were used even out of character, for example, Yvette, a young French Canadian girl, used “wha?” in a few occasions.

Despite these insignificant annoyances, I was captivated by the story and I was ready to finish the masterpiece (!). Then came the turning point, Duddy’s reading of his uncle’s letter. It raised my expectations to the highest levels, but unfortunately Duddy went downhill from that point taking the book with him. To me, a novel is the depiction of rising of human character. If the hero fails so does the book. For the captivating story, I will give 4 hearts to this book.

The following is an essay I had written in December, 2013, while I was an MA student at University of Ottawa’s World Literatures and Cultures master’s program. It contains a student’s inexperience but sleepless nights. May its flaws be forgiven. To quote from it, please use this citation:

Eskicioglu, Lale. “Mordecai Richler and Accusations of Anti-Semitism.”

ReadLit. readlit.com. 2013. Web. <http://readlit.com/book/the-apprenticeship-of-duddy-kravitz-mordecai-richler/>

Mordecai Richler and Accusations of Anti-Semitism

“The author is condemned because Duddy cashes the cheque.”

Charles Foran[1]

“I don’t bother.”

Mordecai Richler, in response to: “A university term paper asked the students to discuss whether Mordecai Richler was anti-Semitic. How would you answer that question?”[2]

This essay will explore the readers’ perception of anti-Semitism in Mordecai Richler’s novel. The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (henceforth Apprenticeship).

Since its publication in 1959, readers of Mordecai Richler’s Apprenticeship have shown wide-ranging reactions to the book. From “masterpiece” to “disgusting,” the book has received all possible qualifiers between the two ends of the spectrum. Some readers have accused Richler, a Jew, of being an anti-Semite. In this essay, I argue that although it is understandable why some readers would find Richler’s writings offensive and consider them to be anti-Semitic, his depiction of the Jewish community of Montreal in Apprenticeship does not project anti-Semitic ideas, and that Richler himself was very sensitive to racism and bigotry. I hope to demonstrate that while an artist’s observed, perceived or even caricaturized depictions of a community may be hurtful to the members of that group, it does not mean that the artist bears any ill will towards that community or wishes to cause any harm. In my examination of the public reaction Apprenticeship and Mordecai Richler have received, I will attempt to delve into the rationale and intent of the author, as much as these can be divined from his other writings, public statements, and what others have said about him and his work. I will provide examples of ‘character witness accounts’, so to speak. I will also try to understand the minority group and diaspora psychologies in the reception of a piece of popular culture.

In conclusion, I will argue that, based on the results of the aforementioned explorations, the suggestion that Mordecai Richler, one of Canada’s greatest and most insightful writers, is an anti-Semite or a self-hating Jew, is, at the very least, misplaced. To support this argument, I will try to discover the source of such allegations and attempt to deconstruct them, as well as searching for the causes of public dismay and anger.

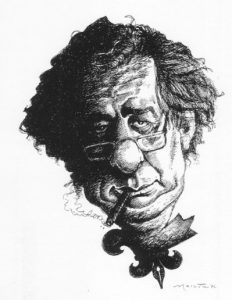

A literary icon:

Mordecai Richler, novelist, playwright, essayist, social critic, journalist and overall a controversial figure, is arguably one of the best-known Jewish Canadians. He was born in Montreal in 1931, and after having given Canada five decades of written culture and much cause for debate, he died in his birth town in 2001. His childhood in Montreal’s tight-knit Jewish community, centered around rue Saint-Urbain, provided much of the material in his fiction.

In 2010, John Barber wrote in The Globe and Mail that judging “by his profile in the media and entertainment industries, no Canadian author alive or dead is as popular today as, the subject of a thick new biography (Mordecai: The Life and Times by Charles Foran), an upcoming documentary (Mordecai Richler: The Last of the Wild Jews), as well as the posthumous inspiration for the soon-to-be-released film adaptation of Barney’s Version.”

Richler’s goal, in his own words, was “to be an honest witness to my time, my place.” He figured, if he was going to be labeled as a self-loathing Jew for a straightforward principle, then so be it: “I don’t bother.” The fact that he did not want to engage his accusers in something he believed to be absurd, did not mean that he was not hurt. He was hurt, that was certain. But he was not going to publicly show his wound. He also anticipated that his community was going to be upset, but he could not predict the kind of reaction he was to receive. About the outrage his 1955 novel Son of a Smaller Hero caused in Canada, he said “I expected people to be hurt, but what I didn’t expect was abuse” (Foran 220).

Jewish self-hatred, Jewish anti-Semite, self-loathing Jew:

What exactly does a self-hating or a self-loathing Jew mean? What is Mordecai Richler really accused of? Antony Lerman, director of the Institute for Jewish Policy Research in London, speaks honestly about this new concept: “The charge of Jewish ‘self-hatred’—another way of calling someone a Jewish anti-Semite—is used ever more frequently, despite mounting evidence that it’s an entirely bogus concept.”

Lerman’s point of departure in his attempt to understand what is meant by ‘Jewish anti-Semite’ is the definition of ‘anti-Semite.’ To put things into perspective, we must note that Richler had known quite a lot of anti-Semitism himself. When Richler was growing up, “Montreal Jewish community was surrounded by anti-Semitism, the endemic result of the Québécois on one side fearing defeat in their fight for sovereignty and the Anglo-Saxons on the other side worrying about Canada losing its WASP majority” (Spergel 8). By the time he was a well-established author, anti-Semitism had been transformed from outright discrimination to a muted social harassment. “The undertones of anti-Semitism worried him a great deal; he pointed out that the Jewish population of Quebec had been reduced by fifteen thousand” (Foran 505). On one hand Richler is worrying about “the undertones of anti-Semitism” and how it drives away the educated and bright Jewish youth from Montreal, on the other hand he is accused of anti-Semitism himself. What exactly is this anti-Semitism which can make one person both the victim and the perpetrator of it?

Lerman explains that 30 years ago there was a common understanding of what anti-Semitism was: “True, historians differed over a precise definition—quite understandably, given that the term was coined only in the 1870s, and was then used to describe varieties of Jew-hatred going back 2,000 years.” However, in the second half of the 20th century, controversy had started to develop “about whether anti-Zionism, or extreme vilification of Israel, was anti-Semitism.” Lerman goes on to assert that the Jews knew who the enemy was:

Since Jews do not cause anti-Semitism, we fought those who peddled theories of the world Jewish conspiracy, Holocaust denial, blood libels. Except at the very margins, we didn’t fight Jews.

How things have changed. Today, bitter arguments rage about what constitutes anti-Semitism. When Jew-hatred is identified, it’s mostly in the form of what many call the “new anti-Semitism” – essentially, anti-Zionism. Others (this writer included) fundamentally dispute that anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism are synonymous […]

The redefinition of anti-Semitism has led to a further radical change in confronting the phenomenon. Many Jews are at the forefront of the growing number of anti-Israel or anti-Zionist groups. So, perceived manifestations of the “new anti-Semitism” increasingly result in Jews attacking other Jews for their alleged anti-Semitic anti-Zionism.

Lerman continues to argue that while in theory there may be Jews who are indeed anti-Semites, he is worried about how and how often such allegations are made. His further remarks apply to Richler and his attackers to the dot:

[I]f you read the growing literature that [exposes an alleged Jewish anti-Semite] – in print, on Web sites and in blogs – you find that it exceeds all reason: The attacks are often vitriolic, ad hominem and indiscriminate. Aspersions are cast on the Jewishness of individuals whom the attacker cannot possibly know.

Many attackers endow their targets with the ability to bring disaster and dissolution to the Jewish people, thereby making it a national and religious duty for Jews to wage a war of words against other Jews.

Lerman concludes that this new, unfair trend does not aid the fight against anti-Semitism and no one benefits. He goes on to say that in this day and age of fear mongering, Jews have “successfully widened the pool of [their] enemies.”

One can easily see the connections between Lerman’s comments and the attacks on Richler. Richler’s tormentors did indeed bestow upon him, or upon his novels, the power of bringing tremendous devastation to the Jewish people. The accusations became so wide-spread that even some of his friends facetiously alleged him of possessing the self-loathing-Jew symptoms. Ted Solotaroff, one of his magazine editors, upon reading one of his pieces, told Richler that he wanted to “go over it carefully and camouflage some of its virulent anti-Semitism. You write like someone who has not yet been told that he is suffering from Jewish self-hatred” (Foran 302).

In 1974, anti-Semitism accusations came again. Richler was asked to write a one-hour long TV drama for CBC’s programme titled The Play’s the Thing. He wrote The Bells of Hell, a story about a Toronto lawyer, who among other troubles has a frustrated sex life. After the play was shot, “[t]he head of CBC television, Thom Benson, citing inappropriate themes and hinting that the film might be offensive to Jews, withdrew it, in part because a Toronto rabbi complained that the script merited comparison to both the ‘ancient anti-Jewish blood libel’ and ‘the more recent doctors’ plot concocted [against Jews] in Moscow in 1953” (Foran 428). After public outrage, the play aired on 24 January 1974.

Apprenticeship: Why does this book upset people?

According to Ann-Marie MacDonald “Richler’s literary legacy is a family of books rich with contradiction, anger, cruelty, generosity, prejudice, merciless insight, and love. Just like a real family” (xiii). Then why are people upset?

What upset people about Apprenticeship was the lack of good characters, lack of great characters, role models. In Apprenticeship, everyone from the Jewish community of rue Saint-Urbain seem to be a failure in one way or another. Most are dishonest by varying degrees. The protagonist Duddy Kravitz is the sleaziest of them all. And yet, he is still the only one who is actually capable of some descent thoughts such as trust and regret. When he feels remorse for directly or indirectly being the cause of Virgil’s accident which leaves him disabled for life, one of his father’s friends tells him not to worry:

A plague on all the goyim, that’s my motto. The more money I make the better care I take of my own, the more I’m able to contribute to our hospital, the building of Israel, and other worthy causes. So a goy is crippled and you think you’re to blame. Given the chance he would have crippled you […] or thrown you into a furnace like six million others. […] They’re all nazis. You scrape down deep enough and you’ll see. (Apprenticeship 304-305)

These are certainly not very flattering images of the Jewish community. One character is a pimp, one of them is a mafia guy, another one is of the opinion that all ‘goyim’ should get the plague, then there is Duddy. But these are images from Richler’s own childhood, they are his own observations. Many of the details in Apprenticeship are taken from his life. His father was a scrap metal dealer, there really was a ‘Wonder Boy,’ many members of the Jewish community summered in Ste-Agatha and the kids waited the tables. Even the episode with the rich man and the bill torn in half had indeed happened (in real life it was a ten dollar bill as opposed to the hundred dollar bill in the book).

While many readers praised the book for being human, colourful, humorous, riveting and painfully honest, others found it insulting and hurtful. Fairly recently, one amazon.com reviewer who writes under the pseudonym mikeg, in a review titled Disgusted with Anti-semitism, has expressed his concerns on the Jewish characters’ offensive portrayals in Apprenticeship:

Every Jewish character is morally corrupt, and obsessed with money, status, and power. The only two redeeming characters are both gentile, who show a deeper meaning in life besides money, who show moral character and friendship beyond self-advancement.

I’m not sure what I’m more disgusted with, the world-war-two-German-type depiction of the deeply moral and faith based Jewish community, or the reviewers who don’t bother to mention the bold and central racist theme.

No, I’m not Jewish, but I shouldn’t have to be ashamed to be Christian.

So, people were upset, or ‘disgusted’ like the reviewer quoted above. Kinder Verlag, his German publisher who had translated his two previous books, The Acrobats and A Choice of Enemies, declined to publish Apprenticeship worrying that it could fuel German anti-semitism (Foran 252). “[T]he ultra-orthodox have identified Richler as a ‘self-hating’ Jew and as having been antagonistic toward Jewish orthodoxy despite his distinguished lineage” (Glass).

Another reviewer on amazon.ca, Bassim Zantout, explores a parallel meaning to the immoral, illegal and reprehensible acts Duddy engaged in to be able to gather the money necessary to buy the land he thought his grandfather meant with his proverbial “a man without land is nobody.” Zantout’s review, titled Does the End Justify Means? offers this alternate interpretation:

The parallel narrative continues to suggest that the founding fathers of the Jewish homeland in Palestine might have perpetrated wrongful, illegal and immoral acts along the way. The most culpable of those is probably the dispossession of the endogenous Palestinian population. Simcha, or Zeyda as he is referred to in the novel, who is Duddy’s grandfather, represents the Jewish conscience. Despite the fact that he passed on to Duddy the notion that a “man without land is nobody”, Zeyda never meant that in the acquisition of this land, one can have recourse to whatever means regardless of their moral or legal standing.

This interpretation may or may not have been on the author’s mind but it is quite likely that some of the anti-Semite accusations came about because of the accusers’ similar readings.

Whenever we hear the news of a fraud or an atrocity, we instinctively fear that the perpetrator of the crime or the objectionable act may be someone from among us, someone from our own community, someone who will bring shame and disgrace upon us, upon our school, work place, neighbourhood, club, village, nation, religious or ethnic community. If we find out that the offender is indeed from among us, we rush to denounce the acts, to clarify that our community is a peace-loving, law-abiding one, that not all of us are the same as the culprit and that there are bad apples in every society. We worry that this one isolated (or repeated) wrongdoing will ruin our reputation and may lead to a reduction in opportunities for our community. In his review of two movies, A Serious Man and Precious, Bernard Beck explains why these worries and sentiments are natural and, for the most part, well-placed:

Minority groups are often justified in being watchful for the difficulties that negative reputations can bring on them. The necessity for discovery and discussion of serious issues within a minority community is real, but the resistance to such a candid approach is founded in their position of vulnerability and the power of old stereotypes. Two recent movies, A Serious Man and Precious, in spite of their enthusiastic reception by movie critics and audiences, are viewed with uneasiness by some commentators in the Jewish and African-American communities. This negative view is predictable and unavoidable. It reminds us that even hyper-sensitive minorities have real enemies. (Beck 152)

Beck’s definition of ‘minority groups’ and his elucidation of ‘representations in popular culture’ perfectly suit our case of Apprenticeship, the book we are scrutinizing in this study and its effects on the Jewish community of Montreal (and indeed on all Jewish communities across Canada):

Groups that maintain unique identities face difficult challenges in a large, noisy society whose other members are not like them. In addition to the practical matters of organization and adequate resources, they must maintain the dignity and admiration of their members and of outsiders. A bad reputation can undermine the support of insiders and the tolerance of strangers. […]

We apply the label “minority” to subgroups that are not only different, but also suspect and vulnerable. They must be especially alert to the dangers of damaged reputation. Many questions about their treatment, their safety, their opportunities, their burdens and their very lives will be answered by the larger society on the basis of their reputations. Are they friendly or hostile, honorable or treacherous, reliable or flaky, weak or strong, smart or dull, admirable or contemptible, attractive or repulsive? All representations in popular culture will carry the freight of these issues, whatever the specific content of the cultural material. All plot lines, all characters, all humor, all melodrama, and all information have possible implications for the general reputation of a group and, consequently, of their social destiny. (Beck 152)

Real or imagined smear campaigns particularly hurt minority groups who “are sensitive to their devalued position in the dominant society,” especially those “with a long history of persecution” (Beck 153). What is humorous social commentary to the safe and secure majority group, is an insult to a minority group.

Going back to A Serious Man and Precious, Beck observes that “[s]ome viewers and commentators have been alarmed, insulted, saddened, or dismayed. These critics have called attention to what they see as a renewal of old, negative stereotypes.” Jews “have been the convenient butts of innumerable jokes and the victims of countless abuses” (155). Similarly, when Apprenticeship brought the stereotypical materialistic Jew depiction to the forefront yet again, of course some readers became “alarmed, insulted, saddened, or dismayed.”

Jewish communities in Montreal and elsewhere are upset not only because Mordecai Richler had cast them in a bad light, they are also upset that he had not depicted them in a good light. They are not simply after ‘neutrality,’ they could use some promotion as well. MacDonald, in her introduction, points out that those were the times when praise for the Canadian Jews were few and far between. Once again, Beck’s account of the importance of a good publicity applies to our case:

They also see the benefits of good publicity. If their starting point is as an alien, suspect force in society, then the chance of acquiring a better image may be an irresistible temptation. The good rep might spare them the hostility and punishment that always seems imminent. Moreover, they cannot worry only about what outsiders think. They must also be concerned with what they think of themselves. To be effective participants in society as individuals and as a group they must maintain and use a powerful culture that reassures, encourages, and guides them. All social creatures use those tools, and minorities cannot do without them either. (Beck 152-153)

Montreal Jewish community and Richler’s very large extended family did not get the “good publicity” and they lost “the chance of acquiring a better image.” Had Richler written about their wonderful hospitality, kind souls, wisdom, parenting skills, all those magnificent qualities, then they were going to embrace their young writer, and they were going to be very proud of him. Richler could have replaced the ‘Boy Wonder’ in their esteem. But Richler was not interested in making up a ‘new’ Jewish community, he wanted to write about the one he knew.

Richler “denounced the tendency to portray the Jew in fiction as someone who is ‘sympathetic, downtrodden, he speaks in parables, and he has a hard time.’” For him, the colourful Jewish character was no more legitimate. He believed that, if he was writing about a corrupt Jewish businessman, pulling punches would have constituted a form of anti-Semitism, not writing about his corruption honestly. He was also aware of the possible damage. He knew that some people would read his portrayals as confirmation of their prejudices. He voiced this concern but he still had to write honestly. Foran quotes him: “If an actual anti-Semite picks up a novel about a corrupt Jew and says ‘This is the way Jews are,’ that is simply ‘one of the dangers you run into’” (220).

Maybe his friend Yanofsky’s words in his book Mordecai & Me, can help us understand why Apprenticeship was not meant to be offensive: “The point missed by people, even communities, who have felt abused by Richler’s fiction, is that his intention was never to make them look bad […] His intention was to make them look interesting” (140). Richler himself, when faced with the self-loathing Jew and anti-Semite charges, stood his ground: “I’m stuck with my original notion, which is to be an honest witness to my time, my place” (Richler qtd in MacDonald xi).

Fuel:

Early on in his career, Richler had already offended the community he grew up in. By mid-to-late fifties he was seen by his fellow Jews “as a renegade exposing his community to the ridicule of anti-Semites” (Barber). He had to live and work for the next forty years with that hostility. Not that he stopped providing the fuel. Charles Foran, novelist and Richler biographer, during his research for his book Mordecai: Life and Times, comes across a particularly incendiary piece of writing among Richler’s archives. This, I believe, is an important and telling evidence in our quest to understand why he was accused of being an anti-Semite Jew:

I discovered Mordecai Richler’s blistering 1973 speech to a Jewish student conference among his papers from the London flat. Curiously, the lecture, typed out in a fury after the reception the night before, was not included in any of the four donations he made over a thirty-year period to the Mordecai Richler archive in the Special Collections, University of Calgary. (705)

At the Jewish student conference, Richer called his audience a company of boors, implied that they were not civilized, he addressed them as moral and intellectual primitives, he went on and on. His speech, or “moral harangue” as Foran calls it, was so incendiary that it is worth quoting it here at some length:

My prepared speech … dealt with present literary confusions, modish philosophies, brutalized sex, and rampaging Canadian nationalism, cultural nationalism, which I consider unfortunate. In a word, it dealt with non-Jewish themes, and I don’t think such matters interest you. You are altogether too narrow. But let it pass. What I’ve really come here to question is the nature of your Jewishness…about which you seem so confident […]

What I’m trying to say is your Jewishness, unlike mine, is distorted, mean-minded, self-pitying, and licensed not by Hillel or Rabbi Akiba, but by urban ignorance. Bigotry born of know-nothingness.

You feel your survival is contingent on the continuing anti-Semitic pressures of the larger community outside, and where they do not exist, you invent them.

Put another way, I heard more anti-Gentile remarks here last night than I have anti-Semitic remarks in years passed in Gentile company. Something else. I have, in years of speaking in public, in Canada, England, and United States, never stumbled among such yahoos before […]

You, my dears, are not only in need of a Jewish education, but a general education. There is hardly one of you, and I include your leaders, who can speak English coherently, let alone grammatically, you are prolix and inchoate. You are unable to postulate intellectual ideas. You confuse name-calling with invective and mistake abuse for wit. Given your mean intellectual equipment, your grasp of real moral dilemmas, I should have thought you would…of necessity…be overcome with modesty. Instead you are aggressive, ignorance your shield, arrogance your armour. You are also sadly mistaken if you think you represent what is best in our long Jewish tradition. (Foran x-xii)

What is important here, is not that Richler is rude or insensitive. What is important is that he despised small-minded ghetto mentality; he valued education and open-mindedness; what he valued most in the Jewish tradition, was not the same as what the majority in his childhood community valued; and, even if he did not know how to address teenagers at a youth conference, he had other sensibilities, he did not want to hear racial slurs against the gentiles, just like he did not want his community to hear anti-Semitic words from the gentiles. After a speech like the one above—harsh, extreme, insulting—it is easy to confuse his ideas and attitudes with anti-Semitism. But he was not an anti-Semite, he was just a different kind of Jew.

On the first anniversary of his death, Richler was remembered fondly, albeit with some of the ‘trickster’ stories: “A year after his death, as in life, memories of Mordecai Richler conjure up conflicting emotions. There is, on the one hand, the delight his humour evoked, along with head-shaking at his irreverence. Michael A. Levine, the high-powered Toronto-based entertainment lawyer and long-time friend, recalls the time he asked Richler to give a reading at his daughter’s private, stodgy and overwhelmingly non-Jewish high school. Richler agreed—on condition, among other things, that he receive a kosher lunch. It wasn’t that Richler was a particularly observant Jew—in fact, the reverse was true. But as he gleefully told Levine: ‘When that kosher delivery truck pulls up to the kitchen door, I want to see the administrators’ faces’” (Wilson-Smith).

Polemicist, mutinous, irreverent, scornful, curmudgeon, standoffish, provocateur, satirist… Just some of the things people have called him. We can all agree that, yes, he was an agitator, a provocateur, a dissenter. Most people who knew Richler agree that he could be accurately described with at least a couple of the names he was called, as listed above. But almost everyone who got to know him also said that he was kind and candid, that he had a soft, sweet and tender side, that he was a loving and caring father, and above all he had impeccable moral values.

We can find some consolation in the fact that Richler was not accused of just anti-Semitism, he was also accused of being anti-Canada, anti-Quebec and anti-French (Foran 570). “His Oh Canada! Oh Quebec! was being called ‘hate propaganda’ in Parliament, a week ahead of its publication” (580). He was not against anyone or any group. He simply spoke his mind on what he thought was wrong or needed improvement. He offended everyone.

Character witnesses have the last word:

One of the many biographies written about Richler is titled The Last Honest Man, and the author, Michael Posner, clearly did not mean it as a slight. This honesty, while difficult or hurtful to take at times, may have been the reason for his ultimate place among highly respected Canadians. His good friend Joel Yanofsky calls him, simply, a nice guy:

It’s commonplace nowadays to discover that a celebrated writer is secretly a pervert or a fraud or a bad tipper; with Richler the opposite is happening. Canadian literature’s most famous curmudgeon is being outed as a nice guy – or at least nicer than everyone suspected. In a recent profile, Richler’s private persona is described by a friend of 50 years as “gentle and warm and generous.” In a review of Barney’s Version by another old friend, former Saturday Night editor John Fraser, Richler is portrayed as a loveable prankster. One reviewer, who made it clear how little he cared for Richler and his politics in the beginning of his review, even conceded that the new novel reveals another, softer, side of its author. During a CBC radio panel discussion, Richler was practically canonized, certainly praised as a national treasure, a kind of disheveled, cigarillo-smoking Anne Murray.

Richler, when needed, was a true fighter for his people. When he went to the Canadian air base in Germany on behalf of the Maclean’s magazine, he wrote The Social Side of the Cold War, “frank, unmediated, driven by a strong personal perspective—it offered a powerful denunciation of amnesia and complacency. […] reporting on the military men and women who sang the praises of their hosts for being ‘so modern, so clean,’ and for having ‘the answer to living’” (Foran 303). He also did not mind exposing the anti-Semitism of one of Canada’s Governor General’s, John Buchan, Lord Tweedsmuir, someone he had been brought up to revere. In a 1968 article on James Bond, while attacking Ian Fleming’s bigotry towards Jews, he made references to Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps, a 1915 espionage novel in which, the future governor general, attributes plots against England to Jewish conspiracies as described in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

“Richler laid out clearly the direct line from Buchan to Ian Fleming, with the enemies of the no-longer ‘Great’ Britain—nasties needing to be taken care of by the ‘licensed to kill’ secret agent—forever resembling those conniving Jews” (Foran 357). This was Mordecai Richler fighting anti-Semitism, even hidden or long forgotten.Foran argues that “[p]eople rarely ‘read’ public figures wrong for long” (xvi). If there is a mask, it is bound to fall down at some point. According to Foran, Richler was not acting, was not pretending to be someone else, and he was not hiding behind a mask. Canadians affectionately called him by his first name, Mordecai, and by doing so, they were “showing their recognition of that truth. The national outpouring on his death in 2001, closer to the responses to the passing of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau or hockey icon Maurice Richard than of even the most admired literary figures from his generation, demonstrated the same unmistakable affection and respect. The highest of praise, surely” (Foran xvi).

Before any of his books were published, or even written, Richler’s alienation from his family and community began when he decided that Judaism had other, more significant connotations for him and that he could no longer accept the ritualistic dogma of orthodoxy. He was still interested in Judaism but not as an orthodox follower. From Ibiza, he wrote to his father that for a book he was planning to write, he had ordered translations of many books on Judaism. He was hoping to soften the blow of his decision to become a secular Jew. His father was not happy and called him selfish and insincere. Richler’s reply to his father also answers many of our questions about him and his character. He wrote:

God, daddy, if I was selfish, I could have remained in Canada, taken a degree, amassed money, and lived a comfortable life. But I believe in what I am doing […] I have faith in the general good and want to create and add to life, truth, beauty, and so to the general good. Is it unfair then that I should ask for help, encouragement, and support from my father? (Foran 125)

He was only twenty when he wrote this letter. He had made the decision to contribute to the general good. And to life, truth and beauty. I choose to take Richler’s word for it. It would be hard for someone who is concerned with the general good, life, truth and beauty to fester and disseminate racial hatred.

Works Cited

Barber, John. “Why Mordecai Richler Isn’t Being Studied in Canadian Universities.” The Globe and Mail. 23-Aug-2012 Web. 16-Dec-2013.

Beck, Bernard. “The Awful Truth: Unflattering Portraits in A Serious Man, and Precious.” Multicultural Perspectives 12.3 (2010). Web. 1-Dec-2013.

Glass, Joseph B. “Mordecai Richler’s Reception in Israel.” Canadian Literature. 207 (Winter 2010):191. Web. 16-Dec-2013.

Foran, Charles. Mordecai: The Life & Times. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2011. Print.

Lerman, Antony. “Jews Attacking Jews.” Haaretz. 12-Sep-2008. Web. 16-Dec-2013.

Posner, Michael. The Last Honest Man: Mordecai Richler, An Oral Biography. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2004. Print.

Richler, Mordecai. The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2001. Print.

MacDonald, Ann-Marie. “Introduction” The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. Mordecai Richler. Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2005. Print.

mikeg. “Customer Reviews – The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz – Disgusted with Anti-semitism” amazon.com. 28-Sep-2011. Web. 15-Dec-2013.

Yanofsky, Joel. Mordecai & Me: An Appreciation of a Kind. Calgary: Red Deer Press, c2003. Print.

—. “Mordecai’s Version: This Year’s Giller Winner Shows Why He’s the Canadian Master of the Satirical Novel.” Quill & Quire 63.12 (1997): 1. Web. 16-Dec-2013.

Wilson-Smith, Anthony. “Mordecai Richler Then and Now.” Maclean’s. 115.25 (2002). Web. 15-Dec-2013.

Zantout, Bassim. “Customer Reviews – The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz – Does End Justify Means?” amazon.ca. 3-Nov-2011. Web. 15-Dec-2013.

[1] The quotation is from John Barber.

[2] The quotation is from Michael Posner’s excerpts from a question-and-answer session with Mordecai Richler, in 1969 at the Saidye Bronfman Centre in Montreal.

[3] One of the primary weapons that the Third Reich used for [an international war of propaganda to convince the rest of the world of the evils of Judaism] was a forgery known as “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” It is claimed that the Protocols are the minutes of a meeting of Jewish leaders at the first Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897, in which Jews plotted to take over the world. The Protocols are a complete forgery most of which was copied from an obscure satire on Napoleon III by Maurice Joly called “Dialogue aux Enfers entre Montesquieu et Machiavel” (The Holocaust History Project).