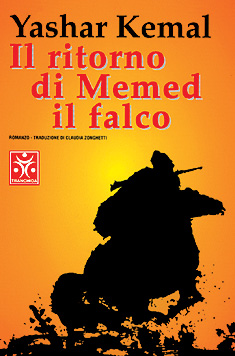

İnce Memed / Memed My Hawk / Mèmed le mince / Memed mein Falke-Yaşar Kemal / Yashar Kemal / Yachar Kemal

İnce Memed / Memed My Hawk / Mèmed le mince / Memed mein Falke –

Yaşar Kemal / Yashar Kemal / Yachar Kemal – 1955

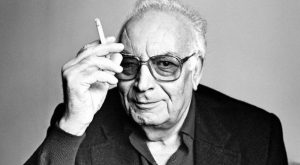

Yaşar Kemal

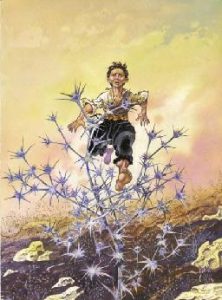

İnce Memed – Drawing by İsmail Gülgeç

~

Posted by Lale on 2/3/2006, 15:14:39

Memed My Hawk: The Turkish title is İnce Memed. “İnce” means thin, skinny, slim, narrow. Memed is a common Turkish name, but the version which is used today is a slightly modernized version: Mehmet. Compared to Mehmet (which is more common in the cities), Memed is considered to be village-like, folksy; also pure, unaltered, authentic.

~

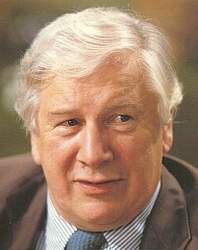

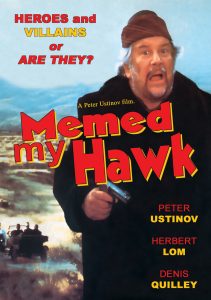

The Movie – Peter Ustinov

In 1984, Peter Ustinov made the movie of Memed My Hawk (also known as The Lion and the Hawk) in which he played Abdi Agha.

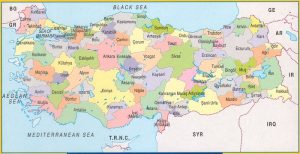

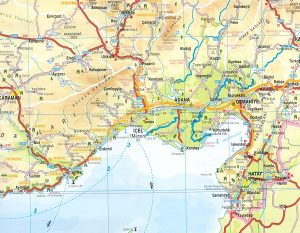

Çukurova – Adana – Taurus Mountains – Posted by Lale on 2/3/2006, 15:19:26

Çukurova (sunken plain) is the name of the delta.

Adana is Turkey’s 4th largest city.

Taurus Mountains – Toros dağları

~

Adana

Situated in the middle of the Çukurova Plain (Cilician Plain), Adana is the fourth largest city of Turkey, nestled in the most fertile agricultural area of the whole country which is fed by the lifegiving waters of River Seyhan.

The city’s name originates in mythology, where it was said to have been founded by Adanus, the son of Kronus (God of Weather).

Due to its being in the heart of that fertile center Adana has been an important city for many civilizations for centuries dating back to the Hittites. The precious River Seyhan is spanned by the ancient Tashköprü (Stone Bridge) which was built by Hadrian and then repaired by Justinian. It is worth noting that to build a 300-yard-long stone bridge in Roman times was a real feat.

Also check out: http://i-cias.com/e.o/adana.htm

Çukurova – Adana – Taurus Mountains – Posted by Lale on 2/3/2006, 15:21:49

Turkey: You can see the Taurus mountain range in this photo (dark green strip along the Mediterranean coast). High resolution true color satellite image of Turkey (Image taken by the MODIS instrument on NASA’s Terra satellite at 08:45 UTC September 21, 2002.)

~

Adana – Posted by Lale on 2/3/2006, 15:26:15

Adana and River Seyhan:

http://encarta.msn.com/map_701516460/Seyhan.html

~

Taurus Mountain range – Posted by Lale on 2/3/2006, 15:28:54

Toros daglari (very dark green over the delta)

~

Toros – Posted by Lale on 2/3/2006, 15:31:18

A view from the Taurus:

~

Çukurova University – Posted by Lale on 2/3/2006, 15:33:42

University of Çukurova

~

Adana Kebab – Posted by Lale on 2/3/2006, 15:39:59

I have never been to Adana but I have eaten a few dishes from its hot and spicy kitchen. Adana Kebab is the most famous. Here is a recipe:

Adana Kebab

Spicy Grilled Ground Veal and Lamb Patties

Adana is a city in southeastern Turkey in the middle of the fertile Cilician (Çukurova) Plain. Its history is ancient; this was the area of the Hittite empire (c. 1800 B.C.). The cuisine of Adana has some influence from nearby Syria, but its most famous contribution to Turkish cuisine is the Adana kebab or köfte, a spicy hot mixture of ground lamb that is grilled. When you come across very spicy Turkish food in western Anatolia, it is a sure sign that it is imported from eastern Anatolia, where they enjoy hotter foods. Adana’s interest in spicy foods might have a medieval origin for in the time of Marco Polo the nearby port of Ayas was an important transhipment place for Asiatic spices and wares; the Venetians, perpetually mesmerized by spices, even had a bailo (consul) there. I’ve changed the basic recipe so one is using ground meat instead of chunks of meat.

3/4 pound ground lamb

3/4 pound ground veal

2 teaspoons cayenne pepper, or more to taste

2 teaspoons freshly ground coriander seeds

2 teaspoons freshly ground cumin seeds

2 teaspoons freshly ground black pepper

Salt to taste

2 tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into tiny pieces

2 pide bread (see Note below)

Extra virgin olive oil, melted unsalted butter, or vegetable oil for brushing

2 medium onions, peeled and sliced

1 tablespoon sumac (a spice found in Middle Eastern markets)

Finely chopped fresh parsley leaves for garnish

1. In a large bowl, knead the lamb, veal, cayenne, coriander, cumin, pepper, salt, and butter together well, keeping your hands wet so the meat doesn’t stick to them. Cover and let the mixture rest in the refrigerator for 1 hour.

2. Prepare a charcoal fire or preheat a gas grill on medium-low for 15 minutes. Form the meat into patties about six inches long and two inches wide. Grill until the köfte are springy to the touch, about 20 minutes, turning often.

3. Meanwhile, brush the pide bread with olive oil, melted butter, or vegetable oil and grill or griddle for a few minutes until hot but not brittle.

4. Arrange the köfte on a serving platter or individual plates and serve with the pide bread, sliced onions, a sprinkle of sumac, and chopped parsley as a garnish.

Note: Turkish (and Greek) style pide bread is not the pocket bread we know as Arabic bread or pita bread. It is a flatbread, though, that needs to be warmed before using, usually to wrap foods in. It can be replaced with pita bread, of course, or even Indian nan bread that you might find in an Indian market. Pide bread can be found in Greek and Middle Eastern markets (often in the frozen food section).

Makes 4 servings

~

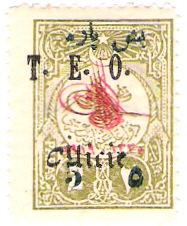

Stamp from Cilicia – Posted by Steven on 7/3/2006, 19:58:18

The postage stamp pictured below was printed for use in Adana and the surrounding area. It tells a bit about the history of the region during the early part of the 20th Century.

This stamp was never used in the mail, but it was repeatedly modified as governments changed, and the existing stock of postage stamps were “overprinted” to reflect new purposes.

The original stamp (only the green part) was a design issued by the Ottoman Empire in 1909. This was the year that Mehmed V became Sultan as part of the revolt of the Young Turks. The green design in the center, mostly obscured by the red overprint, is the “tughra” of Mehmed V, his calligraphic signature.

In July 1918, near the end of World War I, Mehmed V died and was succeeded as sultan by his brother who was crowned Mehmed VI. The following year, after the Empire had been defeated, the existing stocks of postage stamps were overprinted to celebrate the first anniverary of Mehmed VI’s accession. The red design is his tughra, printed on top of that of his brother. The red text is the date “1919” and “1335” in Arabic, the date in the Islamic calendar.

At about the same time, Ottoman postal authorities decided to change the value and purpose of the stamp, and printed over it once more. Typically this is done when inflation makes existing stamps useless, but it’s more economical to overprint them than to print entirely new ones. The blue numbers at the bottom and the text at the top change it from a regular postage stamp worth 2 paras, to a stamp specifically for mailing newspapers, worth 5 paras.

Now come the French. Though the southern parts of the Ottoman Empire had been conquered by the combined forces of the British and Arabs (remember the movie Lawrence of Arabia), a portion was turned over to French administration in 1919. This portion included the modern states of Syria, Lebanon, and a slice of southern Turkey: Cilicia.

The French seized existing stocks of postage stamps and overprinted them to show that they were now valid under the new regime. The innitials T. E. O. stand for “Territories Ennemis Occupes.”

Lastly the stamp was overprinted “Cilicie” to show that it was for use in Cilicia – the setting for our novel.

By the treaty signed by Mehmed VI, Cilicia was to have become part of French Syria rather than Turkey. However, a nationalist revolt by Mustafa Kemal (later surnamed Atatürk), deposed Mehmed VI and repudiated the treaty. In 1923 (the year Yasar Kemal was born) a new treaty was signed, and Cilicia was freed from French occupation, becoming a part of Turkey. Never having been used, our stamp was now invalid for postage and became just a collector’s curiosity.

~

Posted by Lale on 7/3/2006, 20:50:27

Very cool. Thank you Steven. Do you own this stamp?

: Lastly the stamp was overprinted “Cilicie” to show that it

: was for use in Cilicia – the setting for our novel.

Kilikya in Turkish, a name given by the Romans.

Cilician Gates = Gülek (or Külek) pass, through the Tauruses.

http://www.livius.org/a/turkey/cil_gates/gates.html

~

Posted by Steven on 8/3/2006, 8:20:54

: Very cool. Thank you Steven. Do you own this stamp?

Yes, and it’s worth all of fifty cents (US). Even though it has a very complex history, there were evidently hundreds of thousands of copies just like it. The instability at that place and time probably prevented their ever being put into use.

~

Kara MISTIK – Page 8 – Posted by Lale on 3/3/2006, 11:42:40

Kara – dark, black

Mıstık (both “I”s are dot-less) – This is actually not a word and not a name. It is a made-up word that is used as an affectionate nickname for children. It is also a cute name for pets. MISTIK gives me the impression/meaning of “nugget”.

Memed considers to adopt Kara MISTIK as his name but when he is asked, he forgets (or he can’t lie) and he tells his name as ince Memed (Slim Memed).

~~

Posted by Brian on 6/4/2006, 18:45:19

I believe MISTIK is a shortened form of MUSTAFA or with the English spelling MUSTAPHA.

Mıstık is somewhat endearing but also patronizing way to address someone. You would not address someone who commands respect as “Mıstık.”

~~

Uncle – Page 8 – Posted by Lale on 3/3/2006, 11:56:10

In the villages and small towns, you address every one (including total strangers) as

amca or dayı (uncle)

teyze (aunt),

abla (older sister),

abi (aghabey = older brother),

oğlum (my son),

kızım (my daughter),

evladım (my child),

yeğenim (my niece, my nephew) etc.

(“ğ” is not pronounced, it makes the previous vowel longer.)

So, if you are lost in a village and you meet a man you don’t know and you want to ask him for directions, you can address him as “uncle”. Establishes both respect and comradeship, familiarity, closeness.

In cities, of course, you would address a man as “Beyefendi” and a woman as “Hanımefendi”).

~

Allah’s guest – Page 9 – Posted by Lale on 3/3/2006, 12:05:31

Anyone who shows up at your door (a complete stranger, a traveller passing by, a friend of a friend of a friend) and who is in need of shelter and/or food is Allah’s guest. You provide this guest with food and shelter for as long as necessary, for as long as the guest chooses to stay. Traditional Turkish hospitality dictates that you cannot turn the stranger away. You must take them in and give them food and bed.

Back in the olden days this must have come in quite handy for travellers, going from one god-forsaken place to another.

It also works for outlaws. Even if you are running away from the police, you are Allah’s guest and you have shelter in people’s homes.

~

Proper Nouns – Posted by Lale on 3/3/2006, 19:08:00

In this translation (mine is by Edouard Roditi), most names (of people and places) are modified to make them easier for foreign readers to pronounce.

ch is used for c with a cedilla as in Chukurova

sh is used for s with a cedilla as in shalvar

gh is used for g with a bar on top as in agha

j is used for c as in Jennet (The original is Cennet which means Heaven)

Hatche is a popular girls’ name. It is slightly modernized into Hatice.

~

A thousand and one – Page 32 – Posted by Lale on 3/3/2006, 19:14:31

With a thousand and one

– difficulties

– times

– insults

– mishaps

It is a common expression. In Turkish thousand and one is “binbir”.

“I told you a thousand and one times not to enter the house with your shoes.”

~

Inşallah – Page 42 – Posted by Lale on 3/3/2006, 19:28:27

Inshallah – With the permission of Allah / if Allah allows

There are a lot of expressions around Allah. The other day someone sent me this humourous list and I liked it, maybe it is not so funny for people who don’t speak Turkish (or Arabic) but I think you’ll get the idea (you can pretty much carry on a conversation in Turkish by just using these expressions) :

Hopeful, wishful, supportive — INSHALLAH

Before beignning to do something — BISMILLAH

When surprised — ALLAH ALLAH

When leaving — EYVALLAH

To go to the end — YA ALLAH

Promise — VALLAH BILLAH

Self confidence — EVELALLAH

Fully motivated — ALIMALLAH

Bored, irritated — FESUPHANALLAH

More bored — HASBINALLAH

Fed up — ILLALLAH

Great inspiration and motivation — ALLAH, ALLAH, ALLAH

Commenting on someone’s health or success — MASHALLAH

At failure — HAY ALLAH!

~

Posted by LadyPurple on 4/3/2006, 16:41:45

Lale, that is funny! I love it! I have to learn some of these and use them…

Friederike

~

Şerbet (sorbet) – Posted by Lale on 3/3/2006, 22:04:21

I wish I could have find better pictures of sorbet ewers and the guys who sell them. The sorbet seller carries a giant ewer (ibrik) on his shoulder with the long neck of the ewer coming to front under his arm. He bends slightly to pour the sherbet into the little cups.

I searched over an hour for a good photo/illustration of this but all I could find were the following:

No wonder Memed and Mustafa didn’t like sherbet, it is not very good. Today, no Turkish person would ever drink it (not from a street seller anyway). Tourists buy it only for the presentation, just to see the sherbet seller bend and pour the coloured sweet liquid in dainty glasses. It is something to see.

~

Posted by Lale on 3/3/2006, 22:15:16

How about a little contemporary art?

Artist’s name: Eren Eyüboglu, the exhibition is entitled “retrospektif”.

~

Şalvar – Page 51 – Posted by Lale on 4/3/2006, 20:03:06

In the book, shalvar is defined as loose Turkish trousers. They are worn by both men and women. Women usually wear some sort of a skirt on top of their shalvar. The degree of “looseness” varies from town to town. (In Turkey almost every town has its own traditional costume). I am attaching here one photo of a guy and one photo of a woman wearing shalvar. However, to see a variety of Turkish folk costumes I recommend this site:

http://www.dilekisleme.com/urunler.htm

They have nicely classified the Turkish folk outfits by town or locality. They have the outfits for both men (erkek) and women (kadin). In these photos you can also see the stiff, fes-type hats decorated with fake or real coins (women’s outfits). This particular headdress is also mentioned in Memed, My Hawk.

~

Han – Page 61 – Posted by Lale on 4/3/2006, 20:12:34

han = inn

Before the days of hotels, obviously.

~

Helva – Halva – Page 64 – Posted by Lale on 4/3/2006, 20:23:43

There are two kinds of helva:

1. Made with semolina (irmik helvası)

2. Made with crushed sesame seeds and the sesame oil obtained from these crushed seeds (tahin helvası)

I am guessing that the one they buy near the han is the latter, sesame/tahin helvası (because that’s the one you eat with bread).

The semolina helva can be made at home, my mom does it really well.

The sesame seed helva is bought from a store. It is available in many supermarkets here in Canada, I assume it is also available in US. It is very sweet, so you eat it with bread to balance the sweetness. It makes a good, filling meal.

~ Helva Blues ~

One day Nasreddin Hodja felt like eating helva. He would have made some but there was no butter, no sugar and no flour at home. The larder was empty, his stomach was empty and his pockets were empty. He was being tormented with the dream of a huge plate full of helva and he was getting hungrier and hungrier. Finally, he decided to walk down the road to the grocery store.

`Do you have flour?’ he asked the grocer.

`I certainly do, Hodja Effendi.’

`Do you have sugar?’

`Yes, I do.’

`Do you have butter?’

`Yes, Hodja Effendi.’

`So then, what’s holding you back, my friend? Make yourself a good pot of helva and eat it!’

© 2001 Lale Eskicioglu

Helva (halvah, halva, halavah) : A desert made of sesame seeds and sugar. In Hodja’s stories a simpler variation is prepared by flour, butter and sugar. This latter kind is a common food for people with limited means. It tastes great, has nutritional value and easy to make at home. A fancier home version is made with semolina and pine nuts.

SEMOLINA HELVA (irmik Helvası)

Ingredients:

2 cups thick semolina

3/4 cup margarine

1 3/4 cups granulated sugar

3 1/2 cups milk

1/8 cup pine nuts

Preparation :

Melt the margarine in a pan, add the pine nuts and semolina, and sauté over medium heat while continuously stirring until the colour of the pine nuts turns golden brown. Add the milk and stir well, add the sugar and continue to stir. Cover the pan and cook over low heat for 20 minutes, or until all of the milk is absorbed by the semolina. Remove the pan from heat, allow to cool for half an hour, air the helva thoroughly with a spoon, transfer to plates and serve.

~

Page 69 – Eloping / Girl Abduction – Posted by Lale on 4/3/2006, 20:42:28

The lovers are planning to elope. The Turkish expression for this is “girl abduction” even though almost always the girl is a willing party. If a boy likes a girl (and the girl likes him back) but the girl’s family doesn’t want to marry their daughter to this particular boy (because he is poor or because the girl was promised to someone else before) then the boy abducts the girl. The girl cooperates, so the term elope is appropriate, still, it is considered a kidnapping. The lovers spend a night or two outside the village and then they return back. The girl is now damaged goods so the family has no choice but to marry her to the boy who kidnapped her. The previous suitor is no longer interested, in fact, nobody but the abductor would marry a kidnapped girl. This way, the lovers may have their way. Unless, of course, the boy is killed by the girl’s family or by the family of the other suitor. If such a murder occurs then a generations-long “affair of the blood” starts. One family has shed the blood of another thus must be avenged. This way the two families (now blood enemies) keep killing, in turn, one another’s young men for generations to come.

When I was a child, everyday in the newspapers we would read yet another affair-of-the-blood killing. But with the globalization, the migration to big towns, the decline of farming and agriculture (i.e. the village life), and maybe even with education (hopefully), these blood killings have become less and less. One doesn’t read about it in the papers any more. Maybe it still exists but I want to think that it is far less frequent than 30-40 years ago.

~

Hat – Page 106 – Posted by Lale on 7/3/2006, 14:40:33

“Hat reform” (Shapka devrimi) happened in 1925. Ataturk said that a nation on its way to civilization had to wear clothes that were adaptible to the new life, that were practical and compatible with civilization. Shalvar was replaced with pants. Various headdresses (turbans etc.), as well as the North-African fez (fes), were replaced by western-style hats. It was forbidden to go out in public in turban, except for religious leaders.

Atatürk’s reforms (from http://www.allaboutturkey.com/reform.htm):

Atatürk was a military genius, a charismatic leader, also a comprehensive reformer in his life. It was important at the time for the Republic of Turkey to be modernized in order to progress towards the level of contemporary civilizations and to be an active member of the culturally developed communities. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk modernized the life of his country.

Atatürk introduced reforms which he considered of vital importance for the salvation and survival of his people between 1924-1938. These reforms were enthusiastically welcomed by the Turkish people.

Chronology of Reforms

1922 Sultanate abolished (November 1).

1923 Treaty of Lausanne secured (July 24). Republic of Turkey with capital at Ankara proclaimed (October 29).

1924 Caliphate abolished (March 3). Traditional religious schools closed, Sheriat (Islamic Law) abolished. Constitution adopted (April 20).

1925 Dervish brotherhoods abolished. Fez outlawed by the Hat Law (November 25). Veiling of women discouraged; Western clothing for men and women encouraged. Western (Gregorian) calendar adopted.

1926 New civil, commercial, and penal codes based on European models adopted. New civil code ended Islamic polygamy and divorce by renunciation and introduced civil marriage. Millet system ended.

1927 First systematic census.

1928 New Turkish alphabet (modified Latin form) adopted. State declared secular (April 10); constitutional provision establishing Islam as official religion deleted.

1933 Islamic call to worship and public readings of the Kuran (Quran) required to be in Turkish rather than Arabic.

In 1950, a newly elected government’s (Demokrat Parti) first task was to abolish the ban on Arabic “ezan” (call to prayer). So, that was the end of that. Today ezan is still called out in Arabic in Turkey – LE

1934 Women given the vote and the right to hold office. Law of Surnames adopted – Mustafa Kemal given the name Kemal Atatürk (Father of the Turks) by the Grand National Assembly; Ismet Pasha took surname of inönü.

1935 Sunday adopted as legal weekly holiday. State role in managing economy written into the constitution.

~

Posted by Steven on 8/3/2006, 8:35:15

The world could certainly use a few more Ataturks right now. I recall a few years ago, when there were a lot of “best of the century” lists being published, seeing a list that named Ataturk as the single most influtential person of the 20th Century (ahead of men like Lenin, Mao, Gandhi, Churchill, Einstein and Roosevelt).

~

Public Writer – Page 127 – Posted by Lale on 7/3/2006, 14:56:24

In the introduction, Yaşar Kemal says that at some point in his life he was “making a living writing court petitions on my typewriter on a table in the middle of the street.”

This profession is later mentioned in the book, when Hatche’s mother needs a public writer to have a petition filled out. This vocation is called “arzuhalci” in Turkish. Before the personal computers and internet and such, arzuhalci was very popular in Turkey. In the neighbourhood of every courthouse there would be dozens of arzuhalci, sitting on the sidewalks with their typewriters in front of them.

Here is a story from a friend of mine: Maybe 15-20 years ago, he was working in Ankara in a district where the courthouse was (still is) situated. One day, the company he worked for received some guests, “foreign experts”, from Europe. My friend takes them out for lunch, shows them around etc. They see the public writers lined by the buildings, sitting in open air, on the street. Dozens of them, with their little tables and typewriters. The foreign experts want to know what that is all about. My friend, who doesn’t feel like explaining in detail (and there might have been a language problem too), wants to brush the question aside with a quick answer. With an air of “Isn’t it obvious?”, he says: “They are authors, they are writing novels.” One of the guests looks about himself. No sea, no river, no forest, nothing pretty to look at, just a busy commercial district. He asks: “Where do they get their inspirations from?”

~

Posted by Steven on 13/3/2006, 9:32:42

Lale: In roughly what span of years would you say the events of the novel take place? In what I’ve read so far, I haven’t noticed any mention of events or technology that would help place it.

~

Posted by Lale on 13/3/2006, 12:07:16

: Lale: In roughly what span of years would you say the

: events of the novel take place? In what I’ve read so

: far, I haven’t noticed any mention of events or technology that would help place it.

I was under the impression that the story was taking place in the early 30s. (Still the early years of the Republic and a few years after the “hat” reform, which was in 1926.) However, I just searched the internet and I was surprised to find out that the story was in fact taking place in years leading to 1950 when Ismet (Pasha) Inönü’s government was defeated by Demokratik Parti which reversed the Turkish ezan reform and everything started to deviate from Ataturk’s principles.

In a later chapter a reference to Ismet Inönü (Atatürk’s right-hand man, first Prime Minister and, after Ataturk’s death, second president) is made (“I’ll write to Ankara, I’ll write to Ismet Pasha”) which means his party was still in power, which means the date was before 1950.

Lale

~

Correction – Time frame 1930s – Posted by Lale on 18/3/2006, 9:22:27

: I was under the impression that the story was taking

: place in the early 30s. (Still the early years of the

: Republic and a few years after the “hat” reform, which was in 1926.)

My instincts were on the right track. The book indeed takes place in the early 30s. While Atatürk is still alive. He died in 1938.

My husband is reading the sequel. In the sequel one of the characters we meet in the first book makes a reference to Atatürk.

Lale

~

Posted by Steven on 20/3/2006, 12:57:06

Yes, the 1930s makes much more sense. I was really surprised when the police were transporting the two prisoners from one town to another on foot. Surely they at least would have had cars by the 1950s. Even in the 1930s this seems a bit unusual. The only mention of a car in the book that I noticed was that the soles of Memed’s shoes were made from used car tires. I used to have a pair like that.

~

Posted by Lale on 20/3/2006, 13:04:38

: Yes, the 1930s makes much more sense.

Most definitely. I always thought that it was 30s but I was misled by some comments on the net. Since the book is “written” in early 50s, some people must have thought that it was also taking place at that time.

: I was really surprised when the police were transporting the two

: prisoners from one town to another on foot. Surely

: they at least would have had cars by the 1950s. Even

: in the 1930s this seems a bit unusual.

It is normal in 30s. It is a remote and poor area, so I thought that was plausible.

: the soles of Memed’s shoes were made from used car tires. I used to have a pair like that.

No. Really? You couldn’t have. But little Frank in “Angela’s Ashes” has a pair of those (designed by his father), he hates them so much, he prefers to go barefoot.

Lale

~

Posted by Steven on 22/3/2006, 13:19:26

: the soles of Memed’s shoes were made from used car tires. I used to have a pair like that.

:

: No. Really? You couldn’t have.

Yes, they were sandals I bought in Mexico about 25 years ago to wear on the beach.

~

Posted by Steven on 22/3/2006, 13:05:47

I finished Memed over the weekend. The last few chapters moved along very quickly for me. The weather cooperated as well – we got 13 inches of rain in two days, so there wasn’t much to do but read.

It was a very interesting book, and I look forward to discussing it. I certainly don’t mind extending the discussion to overlap the reading of the next book.

Steven

Nomads and Turkomans – Posted by Steven on 15/3/2006, 9:41:13

Lale, would this…

http://www.allaboutturkey.com/nomad.htm

be a description of the nomads like Kerimoghlu and his people?

I’m also confused by the use of the word “Turkomans” in Chapter 16. From what I can find on the web, the word is used in a broad sense to mean all Turkish-speaking peoples, which would include both Memed’s people and the Ottomans.

In the narrow sense, Turkomans (or Türkmen) refers to a group living in Central Asia and northern Iraq, but not in Turkey. However the reminiscences of Big Ismail in Chapter 16 make it sound like the Turkomans are a group in southern Turkey that is distinct from the Ottomans.

My assumption is that Memed’s people are ethnic Turks just like the Ottomans, but from different tribes that were conquered by the Ottomans. Is this correct?

Steven

~

Posted by Lale on 15/3/2006, 20:09:39

: http://www.allaboutturkey.com/nomad.htm

:

: be a description of the nomads like Kerimoghlu and his people?

Yes, exactly. They are Yörüks.

: I’m also confused by the use of the word “Turkomans” in Chapter 16.

Yes, it is indeed very very confusing. I don’t know all about it myself either. I know that Turkmens are a seperate people, like Kurds.

: In the narrow sense, Turkomans (or Turkmen) refers to

: a group living in Central Asia and northern Iraq, but not in Turkey.

Location might vary. We definitely have Turkmens in Turkey today. There is a famous song about their beautiful daughters. So, Central Asia, Northern Iraq plus Turkey plus other places. (They are the people of today’s Turkmenistan.)

: However the reminiscences of Big Ismail in Chapter 16 make it sound like the Turkomans are a

: group in southern Turkey that is distinct from the Ottomans.

Yes, Turkmens are a distinct people. So are Kurds. Yaşar Kemal is Kurdish.

It was all very mixed up and there were quite a few races, religions … It is hard to define Ottoman.

Some lucky people know who they are (with more certainty) because their grandparents have told them what they have learned from their grandparents. In my case, there wasn’t much root-searching or story telling in our family. So, all I know is that my mother’s mother was Cherkez (or Circassian, see below.)

I think anyone who did not belong to any major group such as Turkmen, Kurd, Armenian etc. was supposed to be Turkish.

The Ottoman Empire was quite mixed. Ottomans came from Seljuk Turks who came from Central Asia. But with all the conquering and invading and expanding …

Then, when the Ottoman Empire became “the sick man of Europe”, and when Italy, France, England, Russia and Greece started to invade and “partager” the sick man’s land, Ataturk organized the people to fight the war of Indepence. When they won, he founded the Republic and he said “How happy he who says ‘I am Turkish'”. This meant that whoever said she was Turkish, was Turkish. Everyone became Turkish.

Today, with the glory of the victory fading, people started to think about their origins. But, I don’t know how far back we can go, because before Ataturk, there were no last names. How and where are you going to search? And if you come from a family who isn’t interested in its own history (like mine), then you have to make more research than a Ph. D. student to find out who you really are.

There is a suggestion amongst some Turkish people these days: Instead of saying “we are Turkish” maybe we should say “we are Turkiyeli” (coming from Turkey). It might be a solution.

So, I guess the short answer to your question would be “I don’t really know”.

Lale

~

Circassia

CIRCASSIA [Circassia] , historic region, encompassing roughly the area between the Black Sea, the Kuban River, and the Caucasus, now largely the Krasnodar Territory of SE European Russia. The Circassians are a Muslim people, whose Russian name is Cherkess and whose native name is Adygey. They are now officially classified as three peoples: the Kabarda, in the Kabardino-Balkar Republic; the Circassians or Cherkess, in the Karachay-Cherkess Republic; and the Adygey, in the Adygey Republic. The term Circassian has sometimes been incorrectly applied to all the mountain peoples of the N Caucasus. Known in antiquity, they inhabited the western side of the Caucasus and the Crimea and were known to the Greeks as the Zyukhoy. They were Christianized in the 6th cent. AD but adopted Islam in the 17th cent. after coming under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. In 1829 the Ottoman Turks were forced to cede Circassia to Russia. At this time the Circassians occupied almost the entire area between the main Caucasian range, the Kuban River, and the Black Sea. In the many Russo-Turkish wars in the first half of the 19th cent., the Circassians bitterly fought the Russians. After the Russian conquest of the area, about 400,000 Circassians migrated to Turkey (1861-64). Circassian women were reputed to be great beauties, and many were sold into slavery in Turkey. There are today large Circassian groups in Turkey, Syria, and Jordan.

~

Posted by Brian on 9/4/2006, 22:12:59

I read the original Turkish version of “Mehmet My Hawk” many years ago. [ . . . ]

[ . . . ] I also revisited the book this time in English translation, which gave me an opportunity to reflect upon it with a new perspective.

Here is the summary of my impressions. I have a hard time appreciating “Mehmet My Hawk,” because I cannot relate to anyone in the book. I am from Western Turkey from an upper-middle class family. With the exception of spending some time in the capital Ankara, I have never been outside the westernmost parts of Turkey. When I go back to visit I still stick to the same areas. I have never met or spoken to anyone who is like Mehmet or the other characters in the book, and I have never seen villages like the ones described in the book. Every day, I read books about places I have never visited or time periods I have never lived in without any problems, so I do not know why it should be an issue with “Mehmet My Hawk” but it is.

Also Yasar Kemal is a left-leaning writer (I am not), and he seems to revel in the suffering of the oppressed peasants and the injustices inflicted upon them. After a while I get bored reading the same plot line over and over. Because I do not agree with the writer politically, it makes it difficult for me to read the book. I end up forcing myself, and the events seem artificial and exaggerated. My reaction is not reserved only to Turkish authors. Recently I started reading “No One Writes to the Colonel” by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, which is a nice collection of short stories. I made it through the first story, which is very well written, but could not read one more story about the suffering South American peasants. (I am curious if anyone else shares my recently developed intolerance to depressing stories about the suffering poor.)

[ . . . ]

“Memed” is about the poor peasants who get oppressed by feudal landlords. There is a love story that gets interrupted violently (again by the big-bad-wolf the feudal landlord), which is bound to make you cry. There is much suffering, suspense, and plot reversals. In the end, the underdog hero overcomes the obstacles and revenges his sufferings or he dies a noble death as a martyr for the cause. I will not tell which but it really does not make much difference. It would be a good book with either ending. Or even with an obscure inconclusive ending. If I were the author, I would kill the underdog hero and leave the reader angry about the injustice. I think it is more dramatic and more effective that way. You can read the book to see if Kemal kills the hero, lets him avenge the sufferings of his loved ones, or he ends the book inconclusively.

~

Posted by Steven on 10/4/2006, 10:14:18

Thank you, Brian, for sharing your thoughts on Kemal and Pamuk. Not being as sensitive to the Turkish political issues, I am less inclined to compare the two. To me they are from different generations, writing about different subjects in different styles. Kemal, especially, could just as easily have been writing about Russian, Chinese or Colombian peasants. I enjoyed reading both authors, but would be more inclined to read further in Pamuk’s work simply because Kemal’s novels, as you noted, are more repetitious of theme.

Coming from a rural background and having been exposed to poverty, if not personally impoverished, I can relate more closely to Memed and his community. I was raised on stories of Jesse James, who is probably the closest figure in American folklore to ince Memed. My father proudly claimed that my grandfather (who died before I was born) had once met Jesse and witnessed a demonstration of his prowess with a pistol. (For those not familiar with the legend, Jesse James was an ex-Confederate soldier who, after the American Civil War, turned outlaw to rob from the rich Yankee bankers to support the poor Southern farmers. In reality, there was much more robbing than there was supporting.) I suppose every culture has among its folk heroes a Memed, a Jesse James, or a Robin Hood.

The American authors with whom I would compare Kemal are Hemingway (for style and plot) and Steinbeck (for theme). I wonder if he was exposed to their work?

Aside from its social theme, Memed, My Hawk is principally about obsession and revenge. Notice how the love affair between Memed and Hatche becomes secondary to his desire to take revenge upon Abdi Agha. Memed learns that he can go on without Hatche, but he cannot live without exacting his vengeance.

Hatche herself is one of many characters in the novel who have the right impulses, but lack the strength or courage to carry on the struggle for justice without the assistance of a person like Memed who is capable of transcending personal and cultural barriers. But Memed is incapable of enjoying the fruits of his efforts – he is like a machine that, once turned on, cannot be turned off. Many revolutionaries are like that – the fight becomes more important to them than what they are fighting for.

~

Posted by Lale on 10/4/2006, 10:47:16

: The American authors with whom I would compare Kemal

: are Hemingway (for style and plot) and Steinbeck (for

: theme). I wonder if he was exposed to their work?

In the introduction, he says:

“The Translation Office published a volume of Chekhov’s short stories that greatly impressed me. … In those days, I also discovered and admired Stendhal’s The Red and the Black”

He continues to mention Homer’s Iliad, Dostoevsky’s The Idiot and Cervantes’ Don Quixote.

He finishes his introduction with:

“If I had not discovered modern literature, I would have become a bard, a singer of epic poems. I was on the verge, but then I started elementary school in a village near mine. I went on to read the classics of Russian, French, and British literature, as well as of the East and West, and so it was that I came to have masters such as Stendhal, Chekhov, and Charlie Chaplin.”

: Aside from its social theme, Memed, My Hawk is principally about obsession and revenge. Notice how

: the love affair between Memed and Hatche becomes secondary to his desire to take revenge upon Abdi

: Agha. Memed learns that he can go on without Hatche, but he cannot live without exacting his vengeance.

Yes, very well put. And also, when you cannot trust the enforcers of the law, when the police and almost every authority is corrupt and can be bought by roasting a lamb, there doesn’t seem to be any other solution than to take the matters in your own hands. Throughout the book, everyone, any major or minor character, suggests murder for every problem. It seems like you just have to go and kill the oppressor because there isn’t any other way of getting rid of him. However, I will let Suat speak on this, Memed’s attitude towards this system changes in the sequel.

My question is why didn’t it occur to the peasants to burn the thistles? If you can burn the thistles and not permanently damage the soil, then why all those years, noone has thought of it. Was Memed the smartest guy in that area?

I asked this question to Suat and he had a very interesting answer; again, I will let him speak for himself.

Lale

~

Posted by Lale on 10/4/2006, 11:09:45

Why were the peasants always so ready to switch sides? They never really could sustain any loyalty. In the sequel, they totally turn against Memed.

What do you guys think? Why did noone think of burning the thistles if it was that easy to get rid of such a major problem and why are the villagers so quick to change sides?

Lale

~

Posted by Steven on 10/4/2006, 11:53:17

: In the meantime, what do you guys think? Why did

: noone think of burning the thistles if it was that

: easy to get rid of such a major problem and why are

: the villagers so quick to change sides?

I was puzzled about the burning of the thistles as well. Abdi Agha might have objected for two reasons: (1) It did damage that the villagers didn’t understand or care about, or (2) it was a way of asserting his authority by forcing them to do it the hard way. (There’s also possibility (3), that this has nothing to do with farming and thistles and is just symbolic of the “flames of revolution.”)

In my youth, farmers in our area routinely burned their fields every year or two to remove grass stubble. This was very risky (we almost lost our house once) and unwise in the long term due to erosion. It also can damage fences and animals. But it is generally beneficial for crops. (We’ll come across burning fields again in The Conservationist.)

The changing of sides just seemed to me to be a case of going with the apparent winner out of fear of retribution.

~

Posted by Brian on 11/4/2006, 4:09:18

Why were the peasants always so ready to switch sides?

My guess is their survival instinct. Every man for himself. Often people do not have enough courage to join forces when faced by a strong adversary– even when they could be much stronger than the adversary if they joined forces.

This must be a strange socio-psychological phenomenon. I even remember reading about instances during the Second World War where a few guards would be in charge of thousands of prisoners on the way to concentration camps or at concentration camps where the prisoners could overtake the guards if they tried (after perhaps a few hundred prisoners died). Why didn’t they try to overpower the guards? Is it because no one wanted to be one of the hundred who would die before the guards killed? Or were the prisoners too beaten down spiritually and psychologically to act? Are the oppressed peasants in “Mehmet My Hawk” behaving like the victims in concentration camps?

This starts from childhood. There is always a bully who beats up the other kinds and takes their lunch money. No matter how much bigger and stronger than the rest of the kids he may be, he would not have a prayer of a chance if ten kids got together and jumped on him. They could teach him a lesson if they want to, but it never happens. Instead they choose to kiss the bully’s a** and try to ally themselves with him hoping that he will beat up on the other kids instead. This continues on in adult life as well–like the peasants in the book.

I think it is because the survival instinct is so strong that it overpowers logic.

~~

Posted by Suat on 14/4/2006, 13:40:00

Yaşar Kemal, being a leftist, no doubt knew about Marx & Engels’ thinking on peasants; that as a class they could not be trusted to lead a revolution or even be a part of it.

Peasant question was one of importance for Marxism since its inception: simply put, peasantry is a class of its own and what is to be done with them?

Their conclusion, in short, was that peasantry was too heterogeneous, in fact, it could be divided into at least three parts: big land owners, smallholding peasants and peasant without land (who work for money and to feed themselves). The latter group could be won to proletariat and the first group is clearly at the side of bourgeoisie, but the biggest majority of the peasants, smallholding ones, could sway either way depending on their individualistic interests and current conditions. Due to this dualistic nature of majority of peasants, they could not be deemed trustworthy for the revolutions and they would switch sides at any given opportunity.

This is exactly what happened to Kemal’s peasants at the beginning of the second book. Remember how they were all on Memed’s side, congratulating him and treating him as their hero; it all changed at the beginning of the second book. Another agha came, the cousin of Abdi agha, who turned out to be even a more merciless oppressor than his predecessor and all the peasants started to blame Memed for their troubles and even said Abdi agha had been so nice, this Memed had killed him for no good reason and so on.

Peasants have been living in the same conditions, in a very slow paste life for so many years (even centuries) that it would be almost impossible for them to produce any original thought. They do as they saw from their parents, ancestors. In order to break this chain, infinite loop, one needs to leave this way of living for some time. That is why I think the peasants did not consider burning the thistles themselves, before Memed told them.

Suat.

~

Posted by Brian on 12/4/2006, 22:15:57

Steven;

You said:

“Memed, My Hawk is principally about obsession and revenge. Notice how the love affair between Memed and Hatche becomes secondary to his desire to take revenge upon Abdi Agha. Memed learns that he can go on without Hatche, but he cannot live without exacting his vengeance.”

This is a wonderful observation.

The culture of that region (more Iranian, Kurdish and Arabic than Turkish) puts tremendous emphasis on the need to take revenge. The honor of a family and its men depend on their ability to take revenge for any injustice, disrespect, or dishonor an outsider brings to the family. They are also required to extract severe punishment from the family members who dishonor the family. So the region is rife with blood feuds between families and honor killings within families.

I cannot decide if Mehmet is obsessed with revenge because of an internal driven need or personality trait or because he has no other choice as a result of his upbringing. In other words is it Mehmet who is obsessed with revenge or the society he lives in and the culture he comes from?

~

Overall – Posted by Lale on 13/4/2006, 13:32:55

I did find portions of the book quite tedious and repetitive also, especially the parts that took place on the mountains, the fights and the descriptions at the beginning of every chapter (it was first published as a weekly series in the newspaper Republic (Cumhuriyet)). The quarrels between Sergeant Rejep and Jabbar were very tiresome. When Sergeant Rejep was fatally wounded he just wouldn’t die quickly enough.

It is definitely an old-fashioned style, which is to be expected, as is the case with all the serialized Dickens novels. It is a saga, the idea is “the longer the better”.

You have to understand that some of their conversations are not that ridiculous in Turkish, in their own vernacular. The translation hasn’t captured their peasant talk at all. Initially, I didn’t have the Turkish version and I translated some of the words to Turkish in my mind. For instance “amca” for “uncle”. Later on my husband brough the original from Turkey and I was surprised to see how local their speech was. The translation gave no hint of that. “Uncle” was not “amca” as it would have been where I grew up, but it was “emmi”, a word to be heard only in small villages.

In one case, in the original version, Memed says to Hatche, “Damn you woman!”, this is completely missing in the translation. Translator has decided to leave this out. That particular dialogue (when Iraz and Memed are trying to convince Hatche to go down to the village) is one sentence short in the English version. Maybe because the Turkish audience would, and the foreign readers would not, understand that this was not a betrayal of affection on Memed’s part but just a frustrated exclaimation a man is allowed to say to his wife in those parts of the world?

During fights, those who get hit say “I am wounded” as they fall down or even as they are dying. In the Turkish version they actually say “ahh yandim” which is just a cry of someone in pain. In English it sounds ridiculous but in Turkish it is natural.

Lale

~

Posted by Suat on 14/4/2006, 12:22:40

I read the two books of ince Memed in four days, while I was in Turkey visiting my ailing father in the hospital.

There is no doubt that Yaşar Kemal is a great story teller. He is in fact the one who started this genre (writing about peasants and their daily struggles against nature, governing forces and also against each other), in Turkey.

İnce Memet is the first novel of this kind, which is a story of a simple peasant boy who is forced to become an “eşkiya” to defend his honor and the ones who are dearest to his heart. The story is told in a very fluent and simple way using the dialect of local peasants, except the repetitive and elaborately descriptive pastoral parts that are describing the beauty of Cukurova and Toros mountains. I would have found these writings beautiful if they weren’t repeated at the beginning of each section; after reading a number of sections, I could hardly wait those descriptions of the nature to end to get on with the story. ince Memed is written as daily, newspaper installments, and I believe that it is the reason for those introductory writings in each section.

İnce Memed is a captivating story and once you start it you want to finish it without dropping the book once (of course, I am talking about the Turkish original. The one Lale read, which was a rather new translation, would not have given me same pleasure and feelings based on few pages I read). However, is it great literature? Does it compare to the books of one of the greatest story tellers of our time, Gabriel Garcia Marquez? I don’t think so. Neither in İnce Memed (I & II) nor in any other books I read from Yaşar Kemal, I found great literature. {Who am I to criticize great Yaşar Kemal, but it is my humble opinion?}

My friend Brian compared Yaşar Kemal and Orhan Pamuk. I see only one similarity between the two, which is that they were both supported by strong lobbies to get their names mentioned in Nobel Literary circles as the candidate for Nobel price. Similarity ends there. Yaşar Kemal was promoted by those who are close to him, who loved him, Orhan Pamuk is a self-promoter. Yaşar Kemal is a real intellectual and is (was) a leftist, where in Turkey, all the leftist intellectuals suffered a lot since the foundation of Republic; they were prosecuted, jailed and forced to live very difficult lives. Orhan Pamuk lives a very comfortable life in Istanbul thanks to his inherited wealth. He just put a farce, to get his name mentioned in media outside Turkey to increase his chances of winning the Nobel literary award. After all, have you seen a Nobel Laureate from the third world country who hasn’t been prosecuted by the local governments? He had to have this stint in the court, in his resume, in order to be taken seriously by the Nobel judges and improve his image outside Turkey. This theatrics were so obvious, I don’t think anybody who is thinking clearly was fooled by that.

Back to İnce Memed, I would give it 2.5 stars and recommend it to Turkish-reading audience, unless a better translation emerges.

Suat.

~

Posted by Ladypurple on 17/4/2006, 9:12:51

I was interested in your comments, Suat. It is unfortunate that the English translation does not get good marks with you. I can see the problem of telling the story without the colloquial flair and language. It takes a lot away from the atmosphere.

I haven’t gotten far enough into the story to get bored with repitition but I take yours and Lale’s word for it. The style, though, did remind me of many Russian novels I read about the peasantry there. Your comment about Kemal’s Marxist view about peasants is good, exactly what was said, and rightly so, about the Russian peasants. Even these days the majority of them live the same life that they had decades ago…

So far, I quite like Memed and would probably tend to give it more like 3.5 stars, but that might change once I have finished it.

You know my views on Pamuk, so I will leave comments out.

Cheers

Friederike

~

Memed and the Burned Village – Posted by Steven on 21/4/2006, 10:18:42

If we can return to Memed My Hawk for a bit… what do you think about the episode where Memed and his companions accidentally burn the village? Though it was presented in a comical vein, it put Memed in a bad light at first – as though his obsession for revenge was turning him against the very people he was supposedly trying to help. He could have put down his rifle and helped put out the fire, but he didn’t.

On the other hand, it worked in the long term to his advantage by enhancing his reputation. It also showed that Memed would let neither this incident nor the death of his friends weaken his resolve.

So is Kemal saying something like “the fire of revolution that burns the thistles may also burn a few villages, but we shouldn’t let this necessary sacrifice deter us in the battle against oppression”?

Or is Kemal saying “obsessive hatred, no matter how justified, will only do harm to you and the ones you love”?

Steven

~

Posted by Lale on 21/4/2006, 10:41:28

I don’t have an answer one way or the other, but I did think that that whole episode was taken very lightly by Memed and his groupies. The tracer guy, Lame Ali, he even said something like “Don’t worry, those houses weren’t worth much anyway, they can just build them again.” They either made light of it or they didn’t fret too much. I thought that was wrong. They didn’t even bother to clean their names, they didn’t explain that it was a mistake or that they felt sorry. The houses might have been just made out of mud and dried cow dung but still they were the villagers homes and they contained beds and blankets and whatever meager possessions they might have had. It bothered me that the supposed “good guys” (even though they are bandits) didn’t feel regret enough and didn’t offer any kind of compensation, or even an apology.

Lale

Memed running through the thistles – Illustrated by ismail Gülgeç