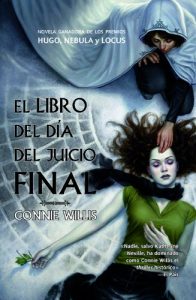

Doomsday Book – Connie Willis – 1992

Cover of the Italian Edition

Posted by Guillermo Maynez on 7/1/2013, 13:51:07

I’m about a third into “Doomsday Book” and enjoying it very much. But something puzzles me (no spoiler, it comes right at the beginning): they are in the year 2054 and don’t have cell phones!! The novel was first published in 1992, when cell phones already existed and were popular. It’s a little weird to see the characters leaving messages in fixed phone lines, and being unable to find each other. What do you think?

~

Posted by Sterling on 7/1/2013, 19:53:58, in reply to “Re: Doomsday Book”

Well, Guillermo, this may be one of the times that Mexico was ahead of the US. Cell phones did not become popular here until about 1998. Before then, a few people had car phones for emergencies, but towers were few and roaming rates (remember them?) were high. I did a quick check of the web, and apparently they became popular in the UK about the same time. A woman on the web said that she first saw them commonly in Italy in 1997. I got my first cell phone in 2000. My wife got hers a year earlier.

It does mar the book a little that Willis did not anticipate the cell phone revolution. (I decided that introduction of the time travel net disrupted the cell signals so seriously that everyone had to revert to land lines.) ;^)

~

Posted by Steven on 7/1/2013, 21:48:01, in reply to “Re: Doomsday Book (non-spoiler)”

Science fiction writers decades previous to Willis had anticipated cell phones or something functionally similar, so I think her keeping Oxford in the Dark Ages, so to speak, had to be a deliberate choice. It may be in part to simplify the story and keep the focus on the human element rather than the technology. There also may be a satirical side to it.

There are two huge technologies introduced in the novel. One of them, of course, is time travel. The other is the chemically implanted translator which Kivrin has. Either one of these has enormous technological and social implications that aren’t addressed in the novel. Imagine the change in the nature of the the university itself if knowledge can be implanted by injection. So I think we just have to accept that the novel is just a vehicle for juxtaposing medieval and modern cultures and not worry about its credibility.

It’s amusing to speculate on what would happen if time travel were invented and operated within the limitations the author prescribes. I can’t imagine that governments would allow universities and historians to have free rein with such a powerful tool. The religious implications alone are earthshaking.

~

Posted by Steven on 10/1/2013, 9:11:43, in reply to “Re: Doomsday Book”

: The religious implications alone are

: earthshaking.

Rethinking my earlier comment, I realized this is wrong. No one is going to change his religious beliefs because of any kind of “proof.” Last week I went with my granddaughter to a new science museum where there was a floor filled with dinosaur fossils. Yet half the people around us were probably religious fundamentalists who believe that the universe is only 6000 years old, and that these fossils are nothing but hoaxes perpetrated by atheists, Satan, or even God himself. Any evidence from a time traveler would be even more suspect.

I’ve also been thinking about the way the Net in Doomsday Book prevents time travel paradoxes by means of slippage. No one can create an impossible situation by, for example, going back in time and causing the death in infancy of one of her own ancestors. At first this sounds too contrived–where does the intelligence come from that steers the time traveler away from conflict?–but thinking back to the ideas we discussed with Ernesto Sábato’s The Tunnel, it makes more sense.

Assuming that everything possible is equally real, and that all moments in what we call the past and the future are coexisting in a larger multi-dimensional reality, then we are just observers selecting which time and which version of reality we experience. Our nature, however, constrains us to move in only one direction in the dimension we call time. But that doesn’t rule out the discovery of some means to change direction in time just as we do in space. However, the matrix of “everything possible” clearly can’t include going back and preventing your own birth, so it’s not just off limits: it isn’t even there. So the Net doesn’t have to steer you out of trouble; you just make timefall at the point of reality nearest your destination.

Another way of looking at time travel–and I think I’ve seen this in at least one novel–is to assume that it is possible to travel in time, but that you can’t go back and visit your own reality. In other words, when you go back in time you also go back into a parallel universe so your actions do not change your own present time. But then you aren’t visiting your own past either, so anything you learn about it is suspect.

~

Posted by guillermo maynez on 10/1/2013, 10:44:46

Time travel is one of the most fascinating ideas: it is so full of interesting possibilities and impossible paradoxes. Unfortunately, according to none other than me, it is impossible. Why? Consider this: at any given moment, the “time” of the Universe is nothing more than the current (infinitesimal in terms of time) arrangement of existing atoms, grouped in molecules. In order to travel in time, you would have to re-arrange those molecules to “tune” them into some other moment. That is: if you wanted to recreate 1320, you would have to order ALL molecules the way they were arranged at a precise moment. But you couldn’t be there!! The molecules currently forming you would be somewhere else, in a different arrangement. Otherwise you would be introducing additional molecules in the pool of the Universe’s, in fact creating matter.

~

Posted by Steven on 10/1/2013, 13:40:23, in reply to “Re: Doomsday Book”

Guillermo, have you ever read Flatland by Edwin Abbott? If not, it’s free as an ebook (in English) and short enough to read online. (Be sure to find a version with the illustrations, though.)

When the Sphere visits Flatland, he appears to pop suddenly into existence out of nothingness–creating matter, as you would call it. But actually he is just moving through a dimension they can’t perceive with their two-dimensional bodies. By analogy, time travel is just moving existing matter through a dimension our three dimensional senses can’t detect.

Another thing to consider is the part of the Theory of Relativity which states that as a body approaches the speed of light, it increases in mass while time slows down. Where does that extra mass come from? Obviously there is some relationship between mass and time just as there is between matter and energy.

Of course the unavoidable question is: “Where are they?” Where are the time travelers from our future. So time travel may be impossible, but for reasons we can’t yet prove. Another equally perplexing question is, if there are billions of other Earth-like planets out there, as now seems to be the case, where are the radio signals and space probes we should expect to be seeing? These are questions that both science and science fiction struggle to answer.

~

Posted by guillermo maynez on 11/1/2013, 12:12:18, in reply to “Re: Doomsday Book”

Thank you for giving me renewed hope that time travel IS possible. I’ve studied some string theory (Brian Greene’s “The Elegant Universe”, for example), but having no formal background in physics, I can’t say I understand it properly (good news is they don’t fully understand it either, ha!). There are supposed to exist no less than 11 dimensions, and multiple and simultaneous universes, so I hope one day I can travel in time.

~

Posted by guillermo maynez on 17/1/2013, 13:35:45, in reply to “Re: Doomsday Book”

OK, so here I go: everything I’ll say about this novel should be read keeping in mind that I DID like it a lot, and that I stayed reading until I couldn’t keep my eyes open, I was so hooked on the events, and the suspense, and the tension.

This novel reads like it was written by a teenager. An exceptionally well-documented one, but still a teenager. Its main characteristic, I’d say, is a strange mixture of naivete and courage. It’s sooooo cute, but at the same time it refuses to give in to sentimentalism. All the last episodes, when the villagers are dying, are written with true grit, with hair-raising realism, with absolutely no concessions to cheapness. I really felt heartbroken when Agnes and then Rosemund died. All that sections, the ones on the life in the manor and surroundings, are, I think, masterful in its recreation. It really takes you there.

The other narrative strand, the one in Oxford, is the downside. It’s not bad, some characters are appealing, but that’s the one that seems to have been written by…. Colin! Apocalyptic! Some long parts of it could have been edited out, including Mrs. Gaddson, and possibly also the bell-ringers, and the lavatory paper, etc. But it’s OK.

Now, I don’t want to sound pretentiously high-brow, but this is clearly a sub-genre book, not artistic literature. Whether it’s sci-fi or historical novel is highly debatable. For my money, all the “future” action could have been 2012 or 1960; the “futuristic” parts are enchantingly old-fashioned, like I was watching reruns of “The Time Tunnel”. Some editing could have benefited it: some sentences are repeated too much (“nowhere to be seen”, “dead to the world”), there are some confusing pieces of information (Sir Bloet is initially in his late twenties, and then around fifty), and the “science” behind the time-travels is unconvincing. Mrs. Willis takes so long getting there, and once she’s at the rescue operation, it all is rushed through and done for in a minute.

There! I had to get that off my chest before saying that it’s really a charming/horrifying novel, redeemed of all its defects by an incredibly brave depiction of a tiny moment in the Middle Ages, and of the morality surrounding some of the characters. Even though no character is psychologically/vitally explored, the whole picture is magnificent. Some initial thoughts.

~

Posted by Sterling on 17/1/2013, 20:55:24, in reply to “Re: Doomsday Book (spoilers)”

It is my opinion that the Oxford sections are intended as comedy. What a person thinks is funny is highly individual. For example, even as a child, I never thought that The Three Stooges were even remotely funny. Most of my contemporaries seem to find them hysterical. I’ve learned not to rent comedy movies, because I rarely find them funny. (American comedies. I often think British comedies are funny.) I admit to chuckling over the lavatory paper, and I thought that Mrs. Gaddson a memorable grotesque.. The intended trick is, I believe, to cause the reader to relax from the solemnity of the 14th century story into the comparatively light-hearted satire of academic politics and comedy of manners. And then to slam the reader with sad and depressing plot developments there as well. Having said that, I definitely think that the 1348 sections are more successful.

I’m not certain why you felt as though it had been written by a teenager. If anything, Ms. Willis’ pacing is too slow. The common mistake of immature and/or neophyte authors is to cram too much incident in (And then he…and then he… and then he…), not to make things feel too drawn out.

It is certainly not “hard” science fiction, in which all the science is true, or at least realistic. I’ve never enjoyed those books very much. They tend to get hung up on boring scientific explanations. For me, the fun of science fiction (and fantasy) is the unbridled imagination. Almost by definition, time travel tales can not have accurate science, even if, as Steven pointed out, it is not totally theoretically impossible.

I think that it’s absolutely charming that an old man and a child step into the fray to rescue her. Perhaps it is rushed. I don’t really think that Willis was especially interested in Colin and Mr. Dunworthy having their own 14th century adventures. In and out.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. It’s one of those books that has remained vivid in my memory since I read it 20 years ago. I was afraid when I proposed it that it wouldn’t wear well. Re-reading it, I was pleased to find that, overall, it’s as fine a genre novel as I recalled.

PS – Willis has written two (or three) other novels about the Oxford Time Travelers: To Say Nothing of the Dog (an all-out comedy) and Blackout/All Clear, published in two halves but actually one long novel. The latter is a direct sequel to Doomsday Book. The opening pages, which I have read on Amazon, feature a 17-year-old Colin looking for Mr. Dunworthy. All three books have won the Hugo, and B/AC won the Nebula (awarded by other writers) as well, like DB.

PPS – This is an interesting review (or perhaps appreciation) by Jo Walton (who won both the Hugo and the Nebula last year):

http://www.tor.com/blogs/2012/06/time-travel-and-the-black-death-connie-williss-doomsday-book

~

Posted by Steven on 18/1/2013, 13:02:59, in reply to “Re: Doomsday Book (spoilers)”

I really appreciate the link to the Jo Walton article because it reinforces my take on the novel that it’s about caring for others, and caring about others. Walton also points out the sorts of things that register only subconsciously when you read it: First, that all the mothers in the story are defective, at best. Eliwys is the only mother who comes close to caring for her children. And second that none of the principal characters has a mate or romantic love interest, and those that do are the subject of ridicule.

One thing Walton didn’t talk about is how Willis’s depiction of Oxford is a parody of academia, with its backwardness, insularity, and turf wars.

It’s also interesting and amusing how she, an American, characterizes Americans vis-a-vis the English. Lupe Montoya and the bell ringers alike are self-absorbed and unable to accept that their own needs and wishes have to be put in a broader context. There is also Mary’s remark about how many tens of thousands died in the pandemic because Americans refused to accept any limits on their personal freedoms. (And I can’t resist noting the parallel between that comment and the current furor over our “right” to own assault rifles and other weapons designed only for mass killing, no matter how many children are sacrificed as a consequence.)

As to the plague itself, the novel could be seen as just a vehicle for having a person with today’s values and preconceptions experience the horrors and the helplessness of the Black Death. The juxtaposition of a modern flu outbreak makes for a fascinating and somewhat chilling comparison.

And of course we are in the midst of a flu outbreak right now. I was reminded of Doomsday Book this week while visiting my mother in the hospital. A number of staff, patients, and visitors were wearing face masks. And my mother’s doctor said he was going to keep her an extra day or two because, if he discharged her too soon and she had to be readmitted, there wouldn’t be a bed to put her in. The rooms are all full, he said, and people are stacking up in the halls in the ER. But, he added, at the rate the staff are falling there soon may not be anyone to take care of her anyway.

Guillermo, until your comment about “Time Tunnel” I had forgotten about that old series. You must’ve seen it in reruns, because it was surely before your time. That was back in the good old days when, even with only three channels, there was more variety on TV than there is now with dozens of channels. Nowadays, as far as I can tell, every drama is a crime drama.

I’m looking forward to reading more by Connie Willis, but before reading To Say Nothing of the Dog I should probably read its inspiration, Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K. Jerome.

~

Posted by Guillermo Maynez on 20/1/2013, 11:18:00, in reply to “Re: Doomsday Book (spoilers)”

Sterling: thank you for the link to Jo Walton’s review. I totally agree with her: in the end, minor anachronisms or any other “mistakes” Ms. Willis may have made are irrelevant before the many strengths of the novel, above all, its being centered on morality and the care for others that shines through it. When I wrote that it seemed to have been written by a teenager, I didn’t mean it in terms of technique, but tone, and it was not derogatory. I meant it has a freshness and a kind of charming naivete, an enthusiasm, that made me feel it like it was written by a very young author. Like Steven, I would like to read “To Say Nothing of the Dog”, but first I should also read its predecessor, “Three Men in a Boat”. Perhaps we could read them together at some point. In any case, here is the value of ReadLit again: “Doomsday Book” would be totally out of my radar, were it not for your recommendation. I’m glad I read it, and the timing was just perfect, Christmas time. All in all, what struck me most about it was the recreation of the time. Short of the technology to allow for physical travel, and maybe even with it, books still are our best time-travel machines.

~

Posted by Sterling on 23/1/2013, 18:50:39, in reply to “Re: Doomsday Book (spoilers)”

Guillermo, the tone of your more recent Doomsday Book post leads me to believe that I must have sounded more defensive than I intended in my previous post. If so, I apologize. As always, I appreciate your thoughts and input. I’m glad that you enjoyed DB as well, but another great value of our ReadLit group is the opportunity to offer different opinions and points of view.

Many year ago, not long after I read Doomsday Book I read To Say Nothing of the Dog. I was disappointed. I think I was looking for a book similar to DB and not really ready for a farce. I might feel differently today, but i probably won’t bother to read it again. I probably will read Blackout/All Clear sometime, although each half is at least as long as DB. I have Three Men in a Boat on my kindle (it was free). My business associate swears it is one of the funniest, if not the funniest book she’s ever read. Maybe we can read that together sometime and see if we have similar senses of humor. :^)

~

Don’t be too misled by the claim that the story takes place in the “future.” If you were to read reviews from ordinary readers, you would find that the people who do not enjoy the book are the “hard SF” crowd who want to pick apart the novel’s lack of future plausibility and/or the lack of any attempt to justify her story in terms of “real” science.

To tell the story she wishes to tell, Ms. Willis required time travel and a translator implant. There is no story without this imaginary technology. Other than that, there is no attempt at “prediction.” Indeed, the story seems to be taking place in about the 1980s, not even the 1990s when it was published.

There is no genre (except romance) that holds less interest for me than the kind of hard science fiction that attempts to predict the way life will be in the future. What a bore! Apparently, Ms. Willis thinks so, too. None of the novels or short stories of hers that I have read remotely relate to the “hard” genre.

So what discipline interests Ms. Willis? History. She spent five years researching Doomsday Book, and the evocation of the fourteenth century is, in my opinion, very impressive indeed. As you will see if you continue to read the novel, Ms. Willis could well have written a straight historical novel (like Wolf Hall), but her interests and intent could not be encompassed in a story that did not explicitly contrast the modern and the medieval.

In short, Doomsday Book does indeed take you to a time in history that you may not yet have read about. Further, as Jo Walton’s invaluable essay points out, the book isn’t about whiz-bang, but about caritas, i.e., the nature of charity and love. I thought it told me truths about the human condition. I suppose with any book, that lies with the individual reader.

Anyway, if you don’t want to read it, please don’t spend the time. But the genre has come a very long way since the days of Isaac Asimov (whom I always found excruciatingly boring even as a kid). The writers at the literary end of the modern sf/fantasy spectrum, such as Gene Wolfe, John Crowley, China Mieville, and, yes, Connie Willis, can write rings around those old school “Golden Age” writers of yore.

PS – I hated the macho banality of The Road. In my opinion, that novel would have sunk like a stone had it been written by a genre writer rather than a well-established writer of literary fiction. I’ve probably read a dozen superior post-apocalyptic novels by actual science fiction writers. Doomsday Book is, in my opinion, much more original, much more touching, much more profound.

~

Posted by Steven on 7/3/2013, 12:10:31, in reply to “Re: Doomsday Book”

I agree with what Sterling says about Doomsday Book. I was a huge SF fan in my younger days, but I did especially like hard science fiction–including Asimov. After years of reading elsewhere, I’m now finding myself drawn back into the genre.

The extent to which SF is about predicting the future has lessened steadily over time. It’s more about giving the author the freedom to create his or her own world for expressing ideas or commenting on the here and now. I don’t think the future world of Doomsday Book has to be any more believable than Lilliput, Erewhon, Macondo, or Middle Earth. These artificial worlds are often just laboratories for ideas that are more easily studied in isolation from the clutter of modern reality.

That’s not to say that many writers don’t strive to show some insight into future developments either in technology or society. But the purpose is likely to be, by extrapolation, to point a cautionary finger at the trends or problems of today. I recently read the Mars trilogy by Kim Stanley Robinson, in which he describes both the technologies used to terraform Mars (i.e. give it an Earthlike environment), and the types of governments and economies developed by the settlers. Yet what he’s really talking to us about are today’s evils of climate change and capitalism.

In other cases, however, science fiction is just way of telling a ripping good story with fascinating characters and the added attraction of an exotic setting. The best works manage to be both entertaining and thoughtful, and I think Doomsday Book is one of those.

Off on a tangent here: many SF writers have borrowed the attributes of earthly cultures to create alien species. (You don’t have to be a Trekkie to realize that the Klingons are Russian and the Romulans are Chinese.) I would be willing to bet that somewhere in the SF canon there is a novel featuring the weregeld system that is so strikingly alien to us in Njal’s Saga.

~

Posted by guillermo maynez on 8/3/2013, 12:57:03

I totally agree with what Sterling and Steven have said about the book. “Doomsday Book” is nothing about the future (it’s the first time I find “the future” a delightfully “retro” future), but about caring for others. And I think Willis had a great idea when she compares what “caring” means in two eras so technologically different as the XIV and XXI centuries. The human value or trait which impels some people to sacrifice themselves for others (while other persons are indifferent to their equals’ suffering) is basically the same, but then the environment plays a part, particularly the state of knowledge in a given society. Thus, Kivrin finds herself desperately alone in a world which attributed disease to supernatural or divine causes, while Mary (the doctor) is much more effective in dealing with the epidemics that she has to face.

The reconstruction of a tiny corner of the Middle Ages is astonishing: what it loses in scope, it gains in detail, by focusing on a micro-microcosmos that examines the minute characteristics of family life, family politics, marriage habits, hygienic conditions, and religious “understanding” of that time and place.

Like our friends say, if you don’t like it, you don’t like it and that’s that. But please don’t read it as a “SF” book, but just a story.

~

- Related:

- Book Reviews