Wolf Hall – Hilary Mantel – 2009

Posted by guillermo maynez on 11/6/2012, 13:39:29

When I was a kid (13-14) I had to spend a couple of weeks at the house of some elderly and spinster aunts in the town of Irapuato, in Central Mexico, the heartland of radical Catholic resistance in the Cristero Wars of the 1930’s. They had a decent library, including several volumes of illustrated, comics-style “Lives of Saints”, of which I read some stories. One that stayed in my mind was that of Saint Thomas More. He was portrayed as a stalwart in the defense of the Faith against the debauched, corrupt, and perverted Henry VIII who, in his illegitimate carnal lust for a whore (they, of course, didn’t use that word), forced a lot of people into sin, and so basically condemned the English nation to Hell. All for Anne Boleyn’s (scarce, according to Mantel) flesh. They, also of course, didn’t mention Henry’s misogyny, since the law allowed the coronation of a female heir, in this case Mary, Catherine’s daughter.

According to this story, Thomas was an excellent husband and father, and I remember very well a vignette where he is teaching Classical Greek to his daughter, surely Meg. So firm a defender of the Faith was he, that he preferred to be decapitated before accepting to be an accomplice in Henry’s diabolical designs. All this I read in the middle of the religious crisis that took me away from religion in general and the Catholic Church in particular.

Turns out that, far from being a saint, Thomas More, according to “Wolf Hall” (and, I suspect, reality) was an extremely selfish and arrogant man, with a Messianic touch, a family dictator, a torturer and fanatic. It chilled me to the bone when, almost at the end of the novel, Cromwell and others are questioning him about his previous orders to torture people for being “heretics”, and the answer he gives, claiming to be right in torture when it is done for Divine Law, instead of the earthly law that makes Henry’s people condemn him. A terrifying justification of torture and bigotry!!

More in the novel itself later.

~

Posted by Sterling on 11/6/2012, 22:58:42, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

Well, it’s not just in the Lives of the Saints. The accepted version of history has always favored Thomas More. Thomas Cromwell is the accepted villain. You need only look at Holbein’s portraits (which Mantel does her best to whitewash) to see how the artist felt about them. (Easily viewed at the Wikipedia entry of each.) The view of More as a Catholic villain torturing Protestants is straight from Foxe’s still debated Book of Martyrs, which I believe to be slanted as extremely to the Protestants as the Lives of the Saints is to the Catholics.

I think it is important to remember that More is not only a Catholic saint but also an English hero. There is a plaque commemorating him in Westminster Hall, where Royals lie in state. A quick Google search located four statues of More in London alone. There are no statues of Cromwell, so far as I can tell.

Mantel is engaged in historic revisionism, where the villain is made the hero. This novel plays the same sort of game as Wicked (the Wizard of Oz told from the point of view of the Wicked Witch of the West) or The Last Ringbearer (The Lord of the Rings as told from the point of view of the denizens of Mordor). I believe it is a clue to her revisionist intent that she chooses to portray Cromwell totally uncritically. The less savory episodes of his life that can not be avoided are glossed over. In my opinion, the novel would have been improved by a more nuanced portrayal of Cromwell — one that remained fundamentally sympathetic but that admitted the darker corners of his soul.

I have not yet finished reading it, so I will say no more. It is a matter of indisputable historical record, though, that More died for his principles, while Cromwell died because he tried to push an unappealing German woman off on the king for political reasons.

If you can find a copy of the DVD of A Man for All Seasons (Oscar-winning Best Picture of 1966), you can see the orthodox view with More as the hero and Cromwell as the villain.

~

Posted by Steven on 11/6/2012, 23:18:27, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

As I mentioned earlier I did most of my background reading in Durant’s Reformation (1957). He devotes only a paragraph to Cromwell, basically describing him as loyal, effective, but ambitious and acquisitive. He spends several pages on More, with a very mixed evaluation, pointing out that More’s actions in persecuting heretics belied the principles he espoused in Utopia. Mantel’s depiction of the two men isn’t inconsistent with Durant’s interpretation, though it slants decidedly in Cromwell’s favor in matters of personality for which there is little historical record.

Posted by guillermo maynez on 12/6/2012, 15:58:53, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

Well, then, I’ll say that as Literary characters, Cromwell is very appealing and More not so.

The main criticism I’ve read of this novel, regarding literature and not history, is the abuse of the pronoun “He”, when sometimes it’s not clear who’s speaking. I understand this is corrected in “Bring up the Bodies”. Nevertheless, I have to say that I enjoyed this novel a lot, and think it is very well written. I’ve had a grand year reading about old England, with Burgess and Mantel.

~

Posted by Sterling on 12/6/2012, 16:55:43, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

I’ve just realized why I find it so hard to stay interested in Wolf Hall. Mantel has been quite scrupulous in adhering to history in terms of incident. This is a period of English history with which I am quite familiar. Consequently, I know everything that’s going to happen. For me, losing the element of surprise with a total lack of suspense kills any narrative momentum.

Burgess had to make up most of Nothing Like the Sun, and while I knew the outcome, I did not know the details of Marlowe’s life. The court of Henry VIII, though, is like reading a novel about, say, the Bush administration. I know the main players, what unfolded, and the eventual outcome. It might be diverting, for a while, if the author made Dick Cheney the hero (and Colin Powell a villain) but the literary device would eventually grow thin.

~

Posted by Lale on 13/6/2012, 15:44:05, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

I was in Vancouver for a week, that’s why I couldn’t write until today. I still have about 80 pages to go. I enjoy it a lot. The book does have a bit of an “element of surprise” because I still don’t know how Mantel’s Cromwell will behave with respect to Anne Boleyn’s downfall.

The author does give us some unsavory character traits of Cromwell. Since the opening chapter we know that he may have killed at least one person and there is the recurring theme of him looking like a murderer. (Based on what I will read in the last 80 pages, the only person he actually murders may be Anne Boleyn but I am not there yet.)

“He” was a problem at the beginning but later on I got used to it.

I would like to read the sequel.

Lale

~

Posted by Sterling on 13/6/2012, 16:49:00, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

I don’t want to run this into the ground. I’m genuinely pleased that you all have enjoyed reading it so much.

It seems to me that the continuing reference to him looking like a murderer is used as a joke. I see him in the novel as kind, generous, charming, humorous, and loyal. He seems to indeed have been loyal, to the extent that there was absolutely nothing that he would not have done for the king. The historic Cromwell appears to have had no principles and no scruples.

The lack of surprise comes because I know exactly what he did to Anne Boleyn. Perhaps Mantel means to make a tragic hero of Cromwell. Start with a noble, honest, honorable man (whom the reader likes). (Book one.) Give him a tragic flaw that leads him to perform a terrible action. (Book two.) His downfall is a direct result of his own flawed behavior. (Book three.) That seems to me to be the only other justification for her extremely positive portrayal of Cromwell, besides the “Wicked” Effect.

~

Posted by Lale on 13/6/2012, 21:19:45, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

I enjoyed the book mostly because it introduced me to a new world and made me look up some things I didn’t know before.

One criticism I have is that the book fails to tell us why Cromwell does all he does. What motivates this guy (there is hint of greed but I didn’t think that was enough to make him work that hard.) Thanks to the supplementary reading on the internet, I learned that he had a “vision.” In the book his political and religious views, and the direction he wants England to take are not presented. It is almost as if everything happened by coincidence, and once he became close to the king he simply could not stop himself from doing as the king wished.

The prophetess (Holy Maid) said that once she got started she couldn’t stop, she had to continue. I felt it was the same with Cromwell, once he became king’s best friend he couldn’t stop being a servant to all his wishes. That’s how it comes across in the book.

But according to other historians and researchers that may not have been the actual case. He seems to have a certain goal (for England). According to some researches, he had his own ideologies and plans for England.

Lale

Posted by Steven on 14/6/2012, 10:10:36, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

Near the end of the book, page 499 of my copy, Mantel states what I think is her thesis for the novel:

“The fate of peoples is made like this, two men in small rooms. Forget the coronations, the conclaves of cardinals, the pomp and processions. This is how the world changes: a counter pushed across the table, a pen stroke that alters the force of a phrase, a woman’s sigh as she passes and leaves on the air a trail of orange flower or rose water; her hand pulling close the bed curtains, the discreet sigh of flesh against flesh.”

This certainly explains why she wrote the novel in a low key fashion and perhaps why a character like Cromwell appeals more to her than someone like Henry VIII or Thomas More. Although from reading this quote you’d get the impression that sex plays a greater role in the novel than it actually does.

~

Posted by Lale on 14/6/2012, 19:55:05, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

I just finished the book. Wow. It was very captivating. I am ready to read the sequel, I should read it before I forget the details of this one. I am disappointed that the book did not cover the fall of Anne Boleyn, instead it was about More. Well, we just need to read the sequel.

I am really confused about the depiction of Thomas More. According to Mantel, he has no redeeming qualities, he is a torturer and a cheapskate who cruelly makes jokes about his rich daughter-in-law’s desire to have a pearl necklace. Who are we going to believe. I am really torn now.

Here at the University of Ottawa, there is a small university street called Thomas More, should I write to the president to have it renamed?

Thanks to this book, I learned so much about the reformation and the details of Christianity. Growing up in an Islamic country, I had never learned as much as you guys knew by high school. This book helped me understand a lot of things and made me very curious for more.

What did you all though about the language/style with which the characters spoke to one another? I don’t think that kind of humour and familiarity was possible with the tool (16th century English in the court) they had. I found some of the dialogs way too familiar, I can’t believe ladies of the court would talk so casually about the king’s and other ladies’ sleeping arrangements. I found the humour very witty but implausible given the time and the place. Some people (including Cromwell) were being a little too friendly with the king and with other high-up people. I wondered how some of the dialogue would sound like in medieval English. On the internet there are some letters written by some of the characters and they don’t seem to speak as causally as in the book.

Lale

Posted by Steven on 15/6/2012, 9:51:28, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

: I am ready to read the sequel,

Do you have it? I’m ready to begin if anyone else is, otherwise I may put if off for a while.

: I am really confused about the depiction of Thomas

: More. According to Mantel, he has no redeeming

: qualities, he is a torturer and a cheepskate who

: cruelly makes jokes about his rich daughter-in-law’s

: desire to have a pearl necklace. Who are we going to

: believe. I am really torn now.

I suspect much of the legend around Thomas More comes from his writings, which espoused humane values he did not practice (not that anyone else did), and his opposition to Henry VIII, who has been demonized for having beheaded two wives. Intolerance was the rule rather than the exception at that time, and all of the principal religious leaders, including Luther and Calvin, encouraged or ordered the killing of those who disagreed with them.

What makes Mantel’s More so unlikable, I think, is not so much what he does but his snide personality in contrast to Cromwell’s sincerity. This is probably just a matter of interpretation.

: Thanks to this book, I learned so much about the

: reformation and the details of Christianity. Growing

: up in an islamic country, I had never learned as much

: as you guys knew by high school.

Actually I’ve learned a lot too. Growing up under any religion means learning only one side of the picture. As an evangelical protestant I was taught that Catholics weren’t even Christians, and that the Pope was the Antichrist. With those kinds of prejudices, it’s impossible to see both sides of an issue.

I just finished reading Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes. It is considered a work of political philosophy, but more than half of it deals with religious issues. Even though it was written a century after Henry VIII, much of it reads as a defense of the English Reformation, so I learned a lot from it to back up what we read in Wolf Hall.

: What did you all though about the language/style with

: which the characters spoke to one another? I don’t

: think that kind of humour and familiarity was possible…

The language Mantel used is probably a compromise between authenticity and readability, leaning heavily towards the latter.

I’ll disagree, though, and say that the language of the court was probably every bit as earthy and intimate as she makes it, if not more so. I think we are deceived by Victorian prudery into thinking that sexual candor is a 20th century invention. Consider that Marguerite de Navarre, the sister of Henry’s rival king Francis I of France, was at this time writing The Heptameron, a series of stories loaded with with sexual escapades and innuendo. And Marguerite was a woman noted for her piety. She and Anne Boleyn were no doubt well acquainted from Anne’s time in the French court.

Posted by Lale on 16/6/2012, 12:25:25

Events around Tyndale are not easy to understand for me. On the one hand King is reading his translation but on the other hand wants him burned. I understood better after reading more on the internet but it is still very confusing since nobody is on one side completely or permanently.

Executions: it is amazing how they do not find a simple beheading not sufficient and they insist on making the convicted suffer by slow burning.

In the next book it will be interesting to read about Mark Smeaton, the choir boy who will be accused of being one of Anne Boleyn’s lovers.

About Cromwell’s role, there are many opposing views quoted in Wikipedia:

According to author and Tudor historian Alison Weir, Thomas Cromwell plotted Anne’s downfall while feigning illness and detailing the plot 20–21 April 1536. Anne’s biographer Eric Ives, among others, believes that her fall and execution were engineered by Thomas Cromwell. The conversations between Chapuys and Cromwell thereafter indicate Cromwell as the instigator of the plot to remove Anne; evidence of this is seen in the Spanish Chronicle and through letters written from Chapuys to Charles V. Anne differed with Cromwell over the redistribution of Church revenues and over foreign policy. She advocated that revenues be distributed to charitable and educational institutions; and she favoured a French alliance. Cromwell insisted on filling the King’s depleted coffers, while taking a cut for himself, and preferred an imperial alliance. For these reasons, suggests Ives, “Anne Boleyn had become a major threat to Thomas Cromwell.” Cromwell’s biographer John Schofield, on the other hand, contends that no power struggle existed between Anne and Cromwell and that “not a trace can be found of a Cromwellian conspiracy against Anne… Cromwell became involved in the royal marital drama only when Henry ordered him onto the case.” Cromwell did not manufacture the accusations of adultery, though he and other officials used them to bolster Henry’s case against Anne. Historian Retha Warnicke questions whether Cromwell could have manipulated the king in such a matter. Henry himself issued the crucial instructions: his officials, including Cromwell, carried them out. The result, historians agree, was a legal travesty. In order to do so the Master Secretary Cromwell would need sufficient evidence that would be convincing enough for her conviction or risk his own offices and perhaps life.

Towards the end of April a Flemish musician in Anne’s service named Mark Smeaton was arrested, perhaps tortured or promised freedom. He initially denied being the Queen’s lover but later confessed. Another courtier, Sir Henry Norris, was arrested on May Day, but since he was an aristocrat, he could not be tortured. Prior to his arrest, Norris was treated kindly by the King, who offered him his own horse to use on the May Day festivities. It seems likely that during the festivities the King was notified of Smeaton’s confession and it was shortly thereafter the alleged conspirators were arrested upon order of the King. Norris was arrested at the festival. Norris denied his guilt and swore that Queen Anne was innocent. One of the most damaging pieces of evidence against Norris was an overheard conversation with Anne at the end of April, where she accused him of coming often to her chambers not to pay court to her lady-in-waiting Madge Shelton but to herself. Sir Francis Weston was arrested two days later on the same charge. Sir William Brereton, a Groom of the King’s Privy Chamber, was also apprehended on grounds of adultery. Sir Thomas Wyatt, a poet and friend of the Boleyns who was allegedly infatuated with her before her marriage to the king, was also imprisoned for the same charge but was later released, most likely due to his friendship or his family’s friendship with Cromwell. Sir Richard Page was also accused of having a sexual relationship with the Queen, but he was acquitted of all charges after further investigation could not implicate him with Anne. The final accused was Queen Anne’s own brother, arrested on charges of incest and treason, accused of having a sexual relationship with his sister. George Boleyn was accused of two incidents of incest: November, 1535 at Whitehall and the following month at Eltham.

On 2 May 1536 Anne was arrested and taken to the Tower of London by barge. It is likely that Anne may have entered through The Court Gate in The Byward Tower rather than The Traitor’s Gate. In the Tower, she collapsed, demanding to know the location of her father and “swete broder”, as well as the charges against her.

In what is reputed to be her last letter to King Henry, dated May 6, she wrote:

“Sir,

Your Grace’s displeasure, and my imprisonment are things so strange unto me, as what to write, or what to excuse, I am altogether ignorant. Whereas you send unto me (willing me to confess a truth, and so obtain your favour) by such an one, whom you know to be my ancient professed enemy. I no sooner received this message by him, than I rightly conceived your meaning; and if, as you say, confessing a truth indeed may procure my safety, I shall with all willingness and duty perform your demand.

But let not your Grace ever imagine, that your poor wife will ever be brought to acknowledge a fault, where not so much as a thought thereof preceded. And to speak a truth, never prince had wife more loyal in all duty, and in all true affection, than you have ever found in Anne Boleyn: with which name and place I could willingly have contented myself, if God and your Grace’s pleasure had been so pleased. Neither did I at any time so far forget myself in my exaltation or received Queenship, but that I always looked for such an alteration as I now find; for the ground of my preferment being on no surer foundation than your Grace’s fancy, the least alteration I knew was fit and sufficient to draw that fancy to some other object. You have chosen me, from a low estate, to be your Queen and companion, far beyond my desert or desire. If then you found me worthy of such honour, good your Grace let not any light fancy, or bad council of mine enemies, withdraw your princely favour from me; neither let that stain, that unworthy stain, of a disloyal heart toward your good grace, ever cast so foul a blot on your most dutiful wife, and the infant-princess your daughter. Try me, good king, but let me have a lawful trial, and let not my sworn enemies sit as my accusers and judges; yea let me receive an open trial, for my truth shall fear no open flame; then shall you see either my innocence cleared, your suspicion and conscience satisfied, the ignominy and slander of the world stopped, or my guilt openly declared. So that whatsoever God or you may determine of me, your grace may be freed of an open censure, and mine offense being so lawfully proved, your grace is at liberty, both before God and man, not only to execute worthy punishment on me as an unlawful wife, but to follow your affection, already settled on that party, for whose sake I am now as I am, whose name I could some good while since have pointed unto, your Grace being not ignorant of my suspicion therein. But if you have already determined of me, and that not only my death, but an infamous slander must bring you the enjoying of your desired happiness; then I desire of God, that he will pardon your great sin therein, and likewise mine enemies, the instruments thereof, and that he will not call you to a strict account of your unprincely and cruel usage of me, at his general judgment-seat, where both you and myself must shortly appear, and in whose judgment I doubt not (whatsoever the world may think of me) mine innocence shall be openly known, and sufficiently cleared. My last and only request shall be, that myself may only bear the burden of your Grace’s displeasure, and that it may not touch the innocent souls of those poor gentlemen, who (as I understand) are likewise in strait imprisonment for my sake. If ever I found favour in your sight, if ever the name of Anne Boleyn hath been pleasing in your ears, then let me obtain this request, and I will so leave to trouble your Grace any further, with mine earnest prayers to the Trinity to have your Grace in his good keeping, and to direct you in all your actions. From my doleful prison in the Tower, this sixth of May;

Your most loyal and ever faithful wife,

Anne Boleyn”

Who might be Anne’s “ancient professed enemy” that she is referring to in the first sentence of her letter to the king, Cromwell?

Lale

~

Posted by Sterling on 16/6/2012, 14:57:07

: Executions: it is amazing how they do not find a

: simple beheading not sufficient and they insist on

: making the convicted suffer by slow burning.

First it’s astonishing how easily the death penalty was handed down. According to the Wikipedia, capital offenses included:

“being in the company of Gypsies for one month”, “strong evidence of malice in a child aged 7–14 years of age” and “blacking the face or using a disguise whilst committing a crime”.

Beheading was generally confined to nobles who had committed an act of treason. Commoners found guilty of treason were hanged, drawn, and quartered.

The Catholic church had decreed that the punishment for heresy be death by burning in the 12th century. The idea was apparently that there would be no body to be resurrected at the Second Coming.

In 1401 an act was passed in England under Henry IV that decreed that heretics would be executed by burning at the stake. This law was not repealed until 1559 under Elizabeth I. (Under her sister Mary I almost 300 Protestant heretics were burned at the stake.) As near as I can tell, Protestants slaughtered Catholics, but they generally did not burn them. Protestants burned witches.

Events around Tyndale are not easy

: to understand for me. On the one hand King is reading

: his translation but on the other hand wants him

: burned. I understood better after reading more on the

: internet but it is still very confusing since nobody

: is on one side completely or permanently.

I’m not really an expert on this, but I’ll take a crack at it. The orthodox point of view of the Catholic church is that the priests, up to and including the Pope, interpret God’s Word for everyone who is not a member of the clergy. The Catholic gains absolution from his sins by confessing to a priest and performing his penance. Catholics are more likely to pray to saints to intercede for them with God than to pray to God himself. Arguably, historically, they are not People of the Book like Jews, Protestants, and Muslims.

It may also be noted that many Catholic tenets, such as the existence of Purgatory, the intercession of saints, the near goddess-like status of the Virgin Mary, and the Papacy itself, are not found in Scripture. Therefore, the Catholic church opposed translating the Bible from Latin into vernacular languages, such as English.

Protestants tend to seek truth within the Bible itself, not from their clergy (although they of course look to clergy for assistance in interpreting difficult passages). Most Protestants, especially the fundamentalists, insist on Scriptural support for any theological assertion. Consequently, they do not believe in Purgatory, the intercession of saints, etc.

The insistence on translating the Bible into the vernacular came from Protestant reformers. The act of translating, possessing, and/or reading the Bible in English was seen as anti-Church and therefore heretical. But, of course, anyone, including the King, might well have been curious to read what is actually written in the Scriptures, which they had never read or heard except through the clergy.

Posted by Steven on 16/6/2012, 19:35:23

: Commoners found guilty

: of treason were hanged, drawn, and quartered.

I wonder what the origin was of this particular sequence of torments or the symbolism behind it? It seems, perhaps, to be a combination of punishments to imply the severest possible penalty. The hanging, in particular, was carried out in such a way as to be non-lethal, so it seems to have been just a symbolic gesture.

Incidentally, women were not hanged, drawn and quartered for treason. Instead they were burned.

: The Catholic church had decreed that the punishment

: for heresy be death by burning in the 12th century.

: The idea was apparently that there would be no body to

: be resurrected at the Second Coming.

It may also have been so there would be no remains or gravesite for the heretic’s followers to venerate. (The same reason the U.S. pitched Osama bin Laden’s body into the sea.)

: I’m not really an expert on this, but I’ll take a

: crack at it.

You did an excellent job!

I would only add that it’s surely no coincidence that the Protestant Reformation coincided with the invention of the printing press. Control of the Bible wasn’t a problem when every volume had to be hand-copied.

Posted by Sterling on 16/6/2012, 12:46:55

I think I derailed much of the discussion of the novel by my irritation at Mantel’s portrayal of historical persons. Mantel is known for this kind of thing. Apparently, in an earlier novel she portrayed Robespierre (architect of the Reign of Terror in the French Revolution) sympathetically. I was appalled at the thought that many readers would think Thomas Cromwell a good fellow if they did not have other knowledge of the court of Henry VIII. And I stick to my guns that her portrait of More is inaccurately negative, even though he doubtless had less attractive sides to his personality than the gentle, witty humorist common in other fictionalizations.

But Mantel is a novelist, not a historian, and of course she has the right to portray any character, historical or otherwise, any way she wishes. Her third person limited point of view has almost the same effect as a first person point of view. Both POVs see the world only through the eyes of of one character. Wolf Hall is not exactly an example of an unreliable narrator (although unreliable third person narratives do exist, Gene Wolfe does it all the time). The historical events are all very accurate. As to the personality of the characters, Cromwell sees himself as the hero (don’t we all to some extent?) and views his friends (Wolsey) positively and his enemies negatively. This is definitely Cromwell’s own self-serving take on the events.

As to the novel itself, I think it is very well written. I think that her dialogue, though much less archaic than either Burgess novel, is handled well. There are no jarring modernisms that would pull one out of the narrative flow. I certainly agree with Steven that these 16th century people would speak in as earthy a fashion as they do here. Rabelais was a contemporary of Henry VIII. Chaucer and Boccaccio wrote a century earlier. There are plenty of explicit sexual and scatalogical references in Shakespeare and the other Elizabethan dramatists, etc. I think Steven hit the nail on the head when he attributed the 20th century belief that they (we) invented sexual candor as a response to Victorian prudery. Victorian prudery was to an extent a reaction against 18th century and Regency licentiousness (Tom Jones, Les Liaisons Dangereuses). History has been a pendulum swinging between licentiousness (Restoration, Regency) and prudery (Puritan Revolution, Victorian).

My only other problem is over familiarity with the period, resulting in the knowledge of almost all notable events in the novel prior to reading. Perhaps that’s why so many historical novelists create a fictional character as their protagonist so that he or she can have their own narrative arc within a frame of historical accuracy. The compensation is that the knowledgeable reader can pick up on foreshadowings (the references to the insignificant Mark) that would be lost on a reader less familiar with the period.

It will be interesting to see how Mantel handles the arrest and trial of Anne Boleyn. Will Cromwell sprout a conscience and show any remorse? Or will he blandly justify himself as he does throughout Wolf Hall?

~

Posted by Sterling on 17/6/2012, 17:20:59, in reply to “Wolf Hall”

Why did Mantel name the novel Wolf Hall?

Not a single scene takes place there. True, it is the home of Jane Seymour, the “next” wife, but that does not seem relevant to this novel. In the novel, at least, there is some report in passing about scandalous behavior at Wolf Hall, but not much is made of it. Do you think that Mantel is comparing the court of Henry VIII to a den of wolves? And since there happens to be a Wolf Hall connected to the story, however tenuously, she used it for the title?

~

Posted by Steven on 17/6/2012, 18:37:56, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

I wondered that myself. I think your theory is probably correct.

Since what eventually became a trilogy was originally planned as a single volume, perhaps Wolf Hall began as her title for the entire work before it was divided into three novels.

I’ve just started Bring Up the Bodies. It begins at Wolf Hall.

Posted by Guillermo Maynez 17/6/2012, 21:36:29, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

This is an excellent thread of discussion. I am writing between spells in airports, but following it closely. I am a born and raised Catholic (no longer believer), so I am pleased to see that your interpretations of Catholic motives and history are correct. Catholics are supposed to understand their religion only through the interpretations of the clergy, and to these days even fanatic Catholics are shockingly ignorant of the Bible, and believe the weirdest ideas, never even hinted at in the Scriptures (such as confession, Purgatory, the Virgin Mary as a goddess, or the saints as valid intermediaries between humans and God). Pope Innocent III (12th Century) invented confession and enforced the previoulsy only recommended celibacy of priests. He is a key figure in the history of Catholic doctrine. There is an excellent novel whose title would be translated as “The Dream of Innocent”, by Mexican author Gerardo Laveaga, but I don’t know if it has been translated to English.

I also agree that pre-Victorian people would have talked very approximately as characters speak in “Wolf Hall”, based on my readings of Chaucer and others.

I liked the novel very much and am looking forward to the sequel, which I’ll get as soon as I can.

~

Posted by Lale on 18/6/2012, 20:34:22, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

: I wondered that myself. I think your theory is probably

: correct.

Me too. I also thought that the word “wolf” may have had something to do with the author’s decision. At the beginning I kept thinking something big was going to happen at the Wolf Hall and justify the title but it didn’t. So it’s probably a combination of the theories you both put forward which I also surmised.

Back to the beheading, it says something about the king when he beheads a person who has been his friend and adviser (or wife) for many many years. Doesn’t that make him look a little stupid?

By the way, more church and Pope and clergy comments and analysis in the Prague Cemetery. (All of you will love that book.)

Lale

~

Posted by Steven on 20/6/2012, 12:11:08, in reply to “Re: Wolf Hall”

: Back to the beheading, it says something about the

: king when he beheads a person who has been his friend

: and adviser (or wife) for many many years. Doesn’t

: that make him look a little stupid?

Or a wise and determined statesman, depending on how you look at it. When the State is embodied in the person of the King and the peace and stability of the realm are threatened by rivals’ claims to the throne, the King has no choice but to act decisively, no matter what his personal feelings.

One of the things that hit home to me while reading history and traveling in Europe is that the royal families pay for all that power and luxury with the knowledge that their personal lives are subject to the needs of the State, and they will have little or no say in whom they marry or where they live. The queen’s role is to breed a suitable heir, and any infidelity on her part is an act of treason as sure as if she had opened the palace doors to an invading army.

Henry comes across to me, if anything, a little weak and tentative. He moved less forcefully than he might have in securing the continuance of his dynasty and needed Cromwell’s continual prodding. Mantel depicts him as an overgrown adolescent whose kingdom is a big toy that he tires of playing with.

: By the way, more church and Pope and clergy comments

: and analysis in the Prague Cemetery. (All of you will

: love that book.)

I’m looking forward to it. Last month I read The Name of the Rose, which also has a lot of information about the religious issues of the late Middle Ages. I’ve also read Hobbes’ Leviathan, of which more than half deals with religious issues and, to top it off, I just finished yesterday my years-long project of reading the King James Bible.

Aside from the religious aspects, I read The Name of the Rose because I’ve been trying, for each book on our schedule, to read any of that author’s major works that came before the book we are scheduled to read. So I’m also hoping to read Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum. Last week I finished reading Smollett’s Roderick Random, and I’ll soon start Peregrine Pickle. And before we get to David Mitchell I hope to at least read Cloud Atlas.

~

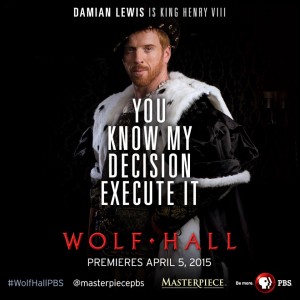

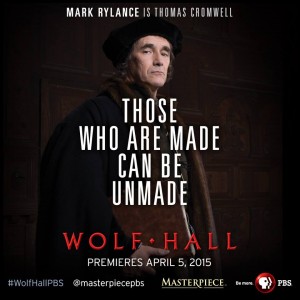

Now a PBS television series:

- Related:

- Book Reviews