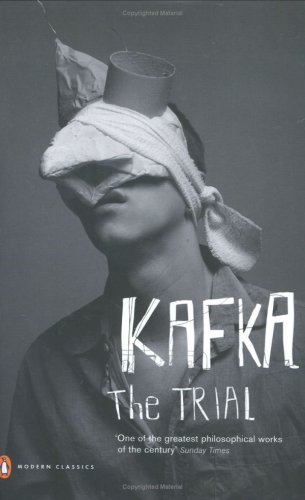

The Trial – Franz Kafka – 1925

Reviewed by: Michael Sympson Date: 2 September 2001

Not until 1982 did I really know the meaning of the term “kafkaesque.” The revelation hit me when I found myself trapped in the middle of Prague, Kafka’s hometown, on a crossroad that received one way lanes from every direction. It was real and surreal and frightening and comical, but nothing dreamy about it. I knew, if I tried to get myself out of this situation, there would inevitably be a very real cop just waiting to give me a very real ticket,. And he did. He was drunk and rather shabbily uniformed.

For many years in my early teens, I had Kafka’s ‘Trial’ on my bedside table. If you want to learn German, this is the book for you. It comes in simple and straightforward language. Kafka was a great admirer of Flaubert and his maxim to tell extraordinary things in ordinary language. So whatever Kafka’s translators may say, Kafka does not exactly pose a linguistic challenge. Still there are differences. The Muirs’ translation, prior to Mitchell’s, is still a respectable piece of late Victorian imitation furniture. But Mitchell does improve, no doubt. However the actual order of the chapters in this unfinished novel is still open to questions — Mitchell’s editors chose to be conservative. As it stands, the “Trial” is a great step forward from Kafka’s first novel ‘America!’ which was written under the influence of Oliver Twist. It has many scenes of burning intensity and a sensual quality, Kafka himself never matched again. However the American backdrop is cut from cardboard and not very convincing. Kafka always had a problem to convey a sense of locality if it wasn’t his hometown. Any reader of Kafka’s “Castle” faces the same problem, the interiors come to life vividly enough, but the geography is curiously vague. The “Trial’s” setting is Prague, and it shows.

For many years in my early teens, I had Kafka’s ‘Trial’ on my bedside table. If you want to learn German, this is the book for you. It comes in simple and straightforward language. Kafka was a great admirer of Flaubert and his maxim to tell extraordinary things in ordinary language. So whatever Kafka’s translators may say, Kafka does not exactly pose a linguistic challenge. Still there are differences. The Muirs’ translation, prior to Mitchell’s, is still a respectable piece of late Victorian imitation furniture. But Mitchell does improve, no doubt. However the actual order of the chapters in this unfinished novel is still open to questions — Mitchell’s editors chose to be conservative. As it stands, the “Trial” is a great step forward from Kafka’s first novel ‘America!’ which was written under the influence of Oliver Twist. It has many scenes of burning intensity and a sensual quality, Kafka himself never matched again. However the American backdrop is cut from cardboard and not very convincing. Kafka always had a problem to convey a sense of locality if it wasn’t his hometown. Any reader of Kafka’s “Castle” faces the same problem, the interiors come to life vividly enough, but the geography is curiously vague. The “Trial’s” setting is Prague, and it shows.

This is perhaps Kafka’s most guilt-stricken story. From scene to scene the shadows thicken until Joseph K.’s providential encounter in the mystical bleakness of the Cathedral. I refuse to speculate on the meaning in all of this, however I would advise against fetching too far for an interpretation. The language is straightforward but still loaded with little pointers and puns. For instance: the protagonist (Joseph K.) has a crush on a certain Miss ‘Bürstner.’ This name is derived from the verb “bürsten” – German for “brushing,” which in German is also a vulgar euphemism for sexual intercourse; and this is no coincidence. There is sex all over the place: the protagonist has an affair with his attorney’s maid, shabbily dressed judges simply carry away women into their chambers, during Joseph K’s conversation with the painter, you hear the painter’s models giggle in the background.

Notice the running parallel between illicit sex and dingy justice. The Viennese critic Karl Kraus had published a series of essays under the title “The Chinese Wall.” In it Kraus attacked Austria’s legal system and spoke up in defence of prostitutes. Kafka knew Kraus, he attended his public readings, and he might have picked up on a phrase Kraus liked to scream at his audience. It began with: “Because justice is a whore … ,” (which no doubt it is.) In Kafka’s novel the courts convene in the strangest places, in attics and lofts, under the rafters of top floors, in sub-tenancies of housing projects. This strange judicial system never allows to approach the upper echelons, but the lower charges are beggarly and sly. The whole state seems to be afflicted by an underground conspiracy, and you never know whether your friendly janitor isn’t one of them. If it were ancient Rome, you could say the slaves are judging their masters.

Joseph K. himself is a somewhat aloof and haughty character, not un-typical for a senior manager. K. works for a bank and he is a sharp dresser and moves with ease in circles of attorneys, chief administrators and CEOs. Kafka lifted out of the text the key-parable, “Before the Law” and published it separately in a collection of shorter pieces. It is difficult to put your finger exactly on the meaning of this famous parable, but it certainly gives the entire novel in a nutshell. In the era of Stalin and McCarthy and after the horrors of the death-camps it has became fashionable to read into Kafka’s novel a brooding indictment against oppression and persecution. I am not so sure: it’s a tough call, because he is never told the charges, yet something seems to be expected of Joseph K., a change of heart perhaps, or a sign of redeeming humility, but K. remains unchanged, his ordeal merely infuses an ever more deepening gloom. One of the great paradigms of modern literature.