The Man Who Was Thursday – G. K. Chesterton – 1908

Chesterton Quotes – Posted by Lale on 19/12/2005, 11:26:08

A businessman is the only man who is forever apologizing for his occupation.

A good novel tells us the truth about its hero; but a bad novel tells us the truth about its author.

A man does not know what he is saying until he knows what he is not saying.

A man who says that no patriot should attack the war until it is over… is saying no good son should warn his mother of a cliff until she has fallen.

A puritan is a person who pours righteous indignation into the wrong things.

A room without books is like a body without a soul.

A stiff apology is a second insult… The injured party does not want to be compensated because he has been wronged; he wants to be healed because he has been hurt.

A woman uses her intelligence to find reasons to support her intuition.

A yawn is a silent shout.

All architecture is great architecture after sunset; perhaps architecture is really a nocturnal art, like the art of fireworks.

All slang is metaphor, and all metaphor is poetry.

An adventure is only an inconvenience rightly considered. An inconvenience is only an adventure wrongly considered.

Art, like morality, consists in drawing the line somewhere.

Artistic temperament is the disease that afflicts amateurs.

Do not free a camel of the burden of his hump; you may be freeing him from being a camel.

Experience which was once claimed by the aged is now claimed exclusively by the young.

I believe in getting into hot water; it keeps you clean.

I was planning to go into architecture. But when I arrived, architecture was filled up. Acting was right next to it, so I signed up for acting instead.

I’ve searched all the parks in all the cities and found no statues of committees.

It is the test of a good religion whether you can joke about it.

It isn’t that they can’t see the solution. It is that they can’t see the problem.

Journalism consists largely in saying “Lord James is dead” to people who never knew Lord James was alive.

Literature is a luxury; fiction is a necessity.

Lying in bed would be an altogether perfect and supreme experience if only one had a colored pencil long enough to draw on the ceiling.

Men feel that cruelty to the poor is a kind of cruelty to animals. They never feel that it is an injustice to equals; nay it is treachery to comrades.

Music with dinner is an insult both to the cook and the violinist.

‘My country, right or wrong’ is a thing no patriot would ever think of saying except in a desperate case. It is like saying ‘My mother, drunk or sober.’

Never invoke the gods unless you really want them to appear. It annoys them very much.

Once I planned to write a book of poems entirely about the things in my pocket. But I found it would be too long; and the age of the great epics is past.

People who make history know nothing about history. You can see that in the sort of history they make.

The Bible tells us to love our neighbors, and also to love our enemies; probably because generally they are the same people.

The only way to be sure of catching a train is to miss the one before it.

There is a great deal of difference between an eager man who wants to read a book and the tired man who wants a book to read.

There is nothing the matter with Americans except their ideals. The real American is all right; it is the ideal American who is all wrong.

To be clever enough to get all that money, one must be stupid enough to want it.

Without education we are in a horrible and deadly danger of taking educated people seriously.

You say grace before meals. All right. But I say grace before the concert and the opera, and grace before the play and pantomime, and grace before I open a book, and grace before sketching, painting, swimming, fencing, boxing, walking, playing, dancing and grace before I dip the pen in the ink.

~

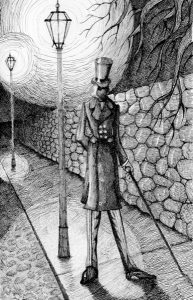

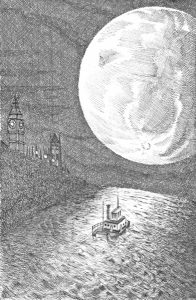

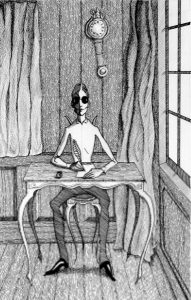

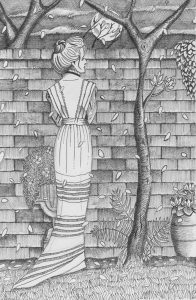

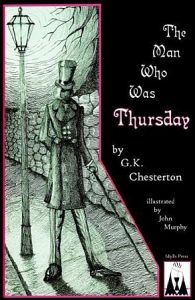

Some of John Murphy’s brilliant illustrations of The Man Who Was Thursday

~

Getting Closer to Sunday

The play on words is intentional! We will start with the discussion on Chesterton’s The Man who was Thursday on Sunday.

Here is a foretaste for things to come …

“It is very difficult to classify The Man Who Was Thursday. It is possible to say that it is a gripping adventure story of murderous criminals and brilliant policemen; but it was to be expected that the author of the Father Brown stories should tell a detective story like no-one else. On this level, therefore, The Man Who Was Thursday succeeds superbly; if nothing else, it is a magnificent tour-de-force of suspense writing.

However, the reader will soon discover that it is much more than that. Carried along on the boisterous rush of the narrative by Chesterton’s wonderful high-spirited style, he will soon see that he is being carried into much deeper waters than he had planned on; and the totally unforeseeable denouement will prove for the modern reader, as it has for thousands of others since 1908 when the book was first published, an inevitable and moving experience, as the investigators finally discover who Sunday is.”

This is from the introduction to the e-version of Thursday.

Friederike

~

Posted by Lale on 25/2/2006, 21:46:00

I just finished it.

It was a nightmare!

However, I must admit, I read the title-page only after having heard Chesterton’s “meek murmur”:

” … those who endure the heavy labour of reading a book might possibly endure that of reading the title-page of a book.”

{from an article by G.K. Chesterton concerning The Man Who Was Thursday published in the Illustrated London News, 13 June 1936 (the day before his death)}

Lale

~

Posted by LadyPurple on 25/2/2006, 21:58:46

LOL! I did the same – I only realized the subtitle at the end of the book… only one woman in the whole story.. What does that tell you??

Friederike

~

Posted by Lale on 27/2/2006, 11:55:33

: only one woman in the whole story..

And only as an extra. She appears at the very beginning and at the very end. She has only one line.

I thought the book was amusing, the idea was interesting and there are some great quotable quotes. But, it really isn’t my kind of book.

Just as they made it to France, my mood was no longer up to it. One night I went downstairs and searched another book. I came up with Brideshead Revisited which wasn’t exactly the right book to shake me back into higher spirits but at least it did keep me interested. Only after finishing Brideshead and the deadline for TMWWT came close, I managed to pick it up again and finish it.

Some scenes are absolutely hilarious but I prefer humour in more realistic settings. The battle scene in a small village in France was impossible to visualize (they are close enough to see but not close enough to catch up), and ultimately, too fantastical for me to enjoy.

Now, as for the philosophy in the book: Chesterton wants us to take it as a “nightmare”. Regardless, there is a lot of social satire and philosophy in the book to discuss. If one of you can kick-off …

Is there a moral of the story? Chesterton implies that no there isn’t, not really. I find that hard to buy. He was definitely up to something. His religious stance is of importance here:

So far as a man may be proud of a religion rooted in humility, I am very proud of my religion; I am especially proud of those parts of it that are most commonly called superstition. I am proud of being fettered by antiquated dogmas and enslaved by dead creeds (as my journalistic friends repeat with so much pertinacity), for I know very well that it is the heretical creeds that are dead, and that it is only the reasonable dogma that lives long enough to be called antiquated.

— From Autobiography (1936) —

I won’t pretend to understand where he stands wrt religion and God, but TMWWT is not just a simple adventure/fantasy book, that much I can figure out.

More from Chesterton sites on the web:

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) was one of the leading literary and apologetic figures in England during the first third of this century. George Bernard Shaw, an atheist, but very good friend of Chesterton’s, called him a “colossal genius,” no doubt wittily intending a double meaning (Chesterton was quite rotund in later years!). In an anthology by a Protestant publisher, he was described as “the ablest and most exuberant proponent of orthodox Christianity of his time” (1). The great Anglican poet, T.S. Eliot said of him: “He did more, I think, than any man of his time . . . to maintain the existence of the important minority in the modern world” (2). C.S. Lewis, arguably the greatest Christian apologist in the era following Chesterton, and also an Anglican, described reading Chesterton as an atheist in 1925:

Then I read Chesterton’s Everlasting Man and for the first time saw the whole Christian outline of history set out in a form that seemed to me to make sense . . . I already thought Chesterton the most sensible man alive “apart from his Christianity.” Now, I veritably believe, I thought that Christianity itself was very sensible “apart from its Christianity.” (3)

When asked what Christian writers had helped him, Lewis remarked in 1963, six months before he died, “The contemporary book that has helped me the most is Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man.” (4)

Chesterton produced nearly a hundred books, including the classics Orthodoxy and The Man Who Was Thursday, and biographies of St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Francis of Assisi. He wrote articles for about 125 periodicals, and was also a talented literary critic, mystery writer, economic and political analyst, social commentator, orator, humorist and poet. He was received into the Catholic Church in 1922.

So, it is all very confusing. Did the man believe in God or not? Did he believe only sometimes?

Kingsley Amis says that he had first read the book as a young boy and then he had read it many times more.

I think it is the kind of book young boys would like. Or at least, it is a book boys (of any age) would like. A little like Lord of the Rings or Don Quixote or Moby Dick. I can’t imagine any woman reading this book more than once.

ReadLiterature.Com’s Smiley Face

Lale

Posted by Guillermo Maynez on 27/2/2006

I just finished TMWWT and liked it a lot. I also have the feeling that I still haven’t managed to uncover secret meanings and religious or moral allegories. The book seems to be very rich in oblique allusions. Taken at face value, the story is highly entertaining, although by the middle of it I had realized who Sunday was: the man in the dark. On a political level, the current situation with terrorism and millennium groups makes the subject itself be relevant.

As to the form of the story, many times it reminded me of “The Master and Margarita”. Chesterton, a profoundly conservative man, seems to mock the world’s view of the terrorist, the simplicity with which they explain the world, and the silliness of anarchists. He is also very talented to project the sheer terror that comes whenever the masses are after you for any reason. Although it includes hilarious episodes, to me it was more properly a nightmare. It terrified me to think that I may live in a terror-state (especially if some presidential candidate wins in Mexico in July).

TMWWT was for me a very rewarding reading experience. I will go on to other books by Chesterton, especially “Orthodoxy” (where he explains his religious views) and the Father Brown stories. Previously, I had only read a very strange fable or allegory called “Manalive”.

~

Posted by Steven on 27/2/2006, 19:09:38

The Man Who Was Thursday was quite a surprising book to read. As soon as you think you have it figured out, it hops to a different level of reality (or unreality), and finishes at a purely metaphysical plane.

Chesterton wrote it at a time when atheism was a rising trend in the intellectual world and a threat to his Christian thinking just as anarchism was a rising threat to the stability of the political system. He uses anarchism, the absence of government, as a symbol for atheism, the absence of God.

Remember that Syme is a poet, not a detective. His nightmare is the dream of a Christian poet confronted with doubt and fear. The dedicatory poem at the beginning of the novel presages what will happen:

“A cloud was on the mind of men

And wailing went the weather,

Yea, a sick cloud upon the soul

When we were boys together.

Science announced nonentity

And art admired decay;…

“This is a tale of those old fears,

Even of those emptied hells,

And none but you shall understand

The true things that it tells–

Of what colossal gods of shame

Could cow men and yet crash

Of what huge devils hid the stars,

Yet fell at a pistol flash.”

My Penguin edition has an introduction by Kingsley Amis in which he says that Chesterton allowed contradictory elements to slip into his writing through a lack of attention. For example, the meeting of the Supreme Anarchist Council is on a sunlit balcony, but minutes later, as the Professor is chasing Syme through London, it is bitterly cold and snowing. I disagree. The snowfall in London, as well as the gloom on the French shore in the later chase scene, are metaphors of the fear and doubt in Syme’s heart, as suggested by the first two lines of the poem.

Each of the supposed anarchists, unmasked, turns out to be a “colossal god” or “huge devil” that easily falls – each doubt or fear turns out to be a source of strength once overcome.

In the concluding scene, each of the men upbraids Sunday for letting them feel so much fear, but Syme says “I see everything” and goes on to ask rhetorically “Why does a dandelion have to fight the whole universe? For the same reason that I had to be alone in the dreadful Council of Days. So that each thing that obeys laws may have the glory and isolation of the anarchist. So that each man fighting for order may be as brave and good a man as the dynamiter. So that the real lie of Satan may be flung back in the face of the blasphemer…”

What he is saying is that each Christian must experience doubt. He must know the loneliness and purposelessness that confronts the atheist, and overcome those doubts through his own reason and faith, the better to be able to “fling back the lie.”

The identification of Syme the poet as “Thursday” is also important. He is identified with the separation of day and night, light and darkness. In other words, it is the poet’s purpose to distinguish between good and evil, truth and lies. That, I would presume, is how Chesterton saw himself.

~~

Posted by LadyPurple on 28/2/2006, 5:56:44

In short, this was quite an intriguing book to read for me. Initially I was taken by the ironies that C. uses to set the scene and describe the characters. London does come to life. Then, later on, that entertainment wore a bit thin. I found some parts, like the description of confrontations in France and even the duel quite boring and somewhat tedious and confusing. At that time, one guesses by that time that everybody other than Sunday is made “from the same cloth”. So the Council members’ “de-robing” was predictable.

I had to remind myself when TMWWT was written and the sort of chaos that was reigning in Europe at the time. That gave it more of a political satire meaning. Which seem to fit with C. career as a political journalist.

Someone described that Syme was the only “sane” person confronting and standing against chaos. This did not come across for me that strongly. I didn’t find Syme very convincing. Maybe I would need to read it again to pick up some of the nuances. But I don’t think I am like Michael Amis re-reading it many times. As Lale said, it’s very much a “guys'” book.

As you say, Steven, there are probably layers of meaning in the story that we miss the first time round, but I guess I stay with that first impression for a while.

The denouement deserves more reflection and comment, probably later…

Friederike

Posted by Lale on 28/2/2006, 11:34:34

The man in the dark who hired Syme was huge. Syme, even though he couldn’t see a thing, knew that the speaker was of massive proportions.

Then, at the first council breakfast, we see that Sunday is a big big man, too big for the balcony. At that moment we know that the two men are one and the same. So, Syme’s and others’ continuing wonders of who Sunday is or who the man who hired them is comes across as childish. We suspect it, why can’t they?

Also, after the first “spy” we know that all of them will turn out to be police officers, so that was a little tiresome too.

But, I really enjoyed some scenes. For instance, Syme’s anticipated dialogue with the Marquis:

‘Has it by any chance occurred to you,’ asked the Professor, with a ponderous simplicity, ‘that the Marquis may not say all the forty-three things you have put down for him?’

Connection to current events: The police (symbolizing all the ruling powers) is as ridiculous as the terrorists. In fact, in the book there are no anarchists, except maybe for Gregory (that poor man, I felt so sorry for him). I am thinking that maybe we can adapt the moral of the story to the current paranoia. We started to think that everyone might be a terrorist. London police killed an innocent man mistaking him for a terrorist.

The silliness of the police also reminded me a little of Bush, how he must have felt after going to war to find weapons of mass destruction and then admitting that there never was any.

Lale

~

Posted by Steven on 28/2/2006, 12:08:10

: I found some parts, like the description of confrontations in France and even the

: duel quite boring and somewhat tedious and confusing.

: At that time, one guesses by that time that everybody other than Sunday is made

: “from the same cloth”. So the Council members’ “de-robing” was predictable.

Yes, I agree. There’s a point where you’re saying “Does he really expect me to sit through this” as he reveals, one-by-one, that all seven are police agents.

On the other hand, scenes such as the one where Sunday is staring only at Syme at their first meeting and where the Professor is inexorably pursuing Syme seem to tap into some universal nightmare and are anything but boring.

: I had to remind myself when TMWWT was written and the

: sort of chaos that was reigning in Europe at the time.

I was hoping for more in the political area. The mindset of someone who murders in the name of universal brotherhood is something I would like to have seen explored, but Chesterton uses anarchism just as an abstraction for evil.

: Someone described that Syme was the only “sane” person confronting and standing

: against chaos. This did not come across for me that strongly. I didn’t find Syme very convincing.

Again, I agree. All the characters, even Syme himself, are players in a dream. Sanity and authenticity aren’t really at issue.

: As Lale said, it’s very much a “guys'” book.

Well, I don’t know about that! The absence of females certainly isn’t one of my critera for male interest ReadLiterature.Com’s Smiley Face

But, seriously, what is there in TMWWT for the reader who isn’t attuned to Chesterton’s theology? As a thriller it has its moments, but those are long gone by the time Sunday hijacks the elephant.

I think it’s primary interest for us is in the way Chesterton builds a religious allegory from what starts out as a detective adventure story. As he unravels the truth about each of the supposed anarchists, he backs further and further away from reality, which only adds to the mystery of where the novel itself is going. For his contemporary readership, who probably knew the verses of Genesis by heart, the ending must have been stunning.

Posted by Lale on 28/2/2006, 15:04:02

: As Lale said, it’s very much a “guys'” book.

:

:: Well, I don’t know about that! The absence of females

:: certainly isn’t one of my critera for male interest

Lack of female characters was not why we said it was a guys’ book. That was a separate, mutually exclusive observation.

It is a guys’ book because guys like adventure/fantasy more, me thinks.

And, I meant to say this before: When I label a book as a guys’ book (I have done this before with Don Quixote, as well as a few others), I don’t mean to imply that in my mind there is also another category in classical literature that attracts women more. I seem to think that good old books (and TMWWT was definitely one of them as Don Quixote and Moby Dick are) maybe appealing to all book-people or just the male ones.

The “guys’ book” comment is not meant to be a compliment or an insult. It simply means that I did not appreciate it as much as some of my friends. As I was reading it, I knew Guillermo, Steven, Pierre, Christopher, Rizwan or Andrew would (quite possibly) like it more than Friederike and I.

Lale

~

Posted by LadyPurple on 28/2/2006, 18:28:52

I agree with you that not being familiar with Chesterton’s theology or much of any other makes the book even more difficult to read at a deeper level. When the group is chasing the so-called anarchist enemies, I was reminded of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. It doesn’t quite fit but the image was very strong in my mind.

A brief comment on the earlier one re ‘guys’ book. I don’t have a problem usually with the absence of women in the story, but this one strikes me as too focused on the male anarchists with their little games. Also, I am somewhat sensitive these days as I am doing research into gender equality and the absence (more likely) thereof…

Friederike

Posted by Lale on 09/7/2016, 17:23:50

Has anyone read Song of Solomon (1977) by Toni Morrison? Did you notice the similarities? The concept of an anarchist for each day of the week seems to be almost identical in both books.