The Grapes of Wrath – John Steinbeck – 1939

Reviewed by: A. J. Date: 10 January 2001

The voice of a million oppressed workers.

Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” is a fictionalized account of the plight of migrant farm workers in California during the Great Depression. Dust storms and poor irrigation have turned large areas of farmland in the prairie states into a Dust Bowl. Tenant farmers, unable to grow crops and pay rent to their landlords, have been forced off their land by the banks. The starving farmers are lured to California by the promise of plentiful fruit-picking jobs, only to find it an unattainable paradise.

The novel follows the pilgrimage of an Oklahoma family named the Joads and their friend, a former preacher, named Jim Casy. When the novel begins, Tom Joad has just gotten out of prison and returns home to find that his family is one of the many that have been dispossessed by the land-owning company. They are preparing to drive to California to seek better farming opportunities. The road to California is a wasteland of unfriendly cops, opportunistic salesmen, unemployed drifters, and lonely souls, all seen from the vista of the Joads’ rickety truck. The chapters alternate between the Joads’ specific experiences and interludes that give a sort of large-scale third-party perspective to the general plight of the land and the people.

Once in the fertile valleys of central California, the Joads learn the reality of the job situation: The farm owners have lured many more people than necessary to fill the available jobs, so they get to hire those who are willing to work for the least money. The surplus of migrant farm workers group together in encampments called Hoovervilles and wait desperately for news about new jobs, while they are forced to face the hostility of the locals who call them “Okies” and consider them wage-deflating scabs. The living conditions are deplorable and the Joads can barely afford the most meager of food.

The Joads eventually find work picking peaches at a large farm that operates almost like a labor camp, with armed guards stationed around to ensure there are no worker uprisings. It is here that Casy, who has been rallying for worker unionization, is martyrized when he is killed by a goon trying to break up a worker strike. Towards the end of the book, in Tom’s “farewell” speech to his mother, Steinbeck conveys his message of the importance of worker organization and unionization to prevent exploitation by employers.

“The Grapes of Wrath” is thoroughly depressing to the very end. It has been accused of being too didactic and heavy-handed, but it’s a book that needed to be written and one that took a lot of guts to do so. Who else but Steinbeck could have treated the downtrodden with so much dignity and sympathy without being condescending? Who else could have invested so much detail in even the seemingly least important characters, such as the one-eyed man in the junkyard, the storekeeper at the peach farm, and the fervently religious Lisbeth Sandry, making them unforgettable symbols of humanity? This book is an education. After reading it, everything else seems shallow.

Posted by Lale on 22/3/2002, 13:44:41

Even though I am only half way through this book, I know, already, that it is one of the best books ever written and one of my all time favourites.

(The story is sad, and I can see where it is going, and I am not going to be surprised by any part of it, but I would still appreciate it if you tried not to give away major twists and turns, if there are any.)

Every now and then, the narration is interrupted by brilliant, self-contained little chapters, that can be read individually, totally independent of the flow of the story. These little chapters are like the ones Michael Sympson wants us to read, from War & Peace and Anna Karenina. These chapters are very demonstrative of the virtuosity of Steinbeck, not only as a story-teller but also as a movie-maker who creates imagery for the eye of the mind. There is one (chapter 3) describing a toad crossing the road, there is another one (chapter 7) describing Used Car shop and some of the deals that take place there. Then there is the one with a brief philosophy on the social order, world economics and cause/response movements (chapter 14).

There is a scene in a road-side diner. I have two questions. One is less important:

“The signs on cards, picked out with shining mica: Pies Like Mother Used to Make. Credit Makes Enemies, Let’s Be Friends. Ladies May Smoke But Be Careful Where You Lay Your Butts. Eat Here and Keep Your Wife for a Pet. IITYWYBAD?”

So, the first question is, what is IITYWYBAD?

For the second question:

This diner belongs to the husband and wife couple Al and Mae. Al cooks and Mae serves. There are two truck drivers inside the diner. Their coffee and pie will cost 15 cents per person but they will both leave a quarter each (that’s what most truck drivers do).

While the truck drivers are enjoying their coffee and pie, a poor family come in. They ask if they can have some water (there is a hose outside). Then they ask if they can buy a loaf of bread for a dime. Mae has all sorts of excuses. She says they can’t sell bread (“it’s not a grocery store here”), they need them for sandwiches, why can’t they buy sandwiches (“we can’t afford them ma’am”), and a loaf of bread is 15 cents not a dime. Al yells to Mae a few times “give the man the bread, Mae”. Mae is very reluctant. It takes Al a few tries to convince her to give a loaf of bread for a dime. Truck drivers are watching. Then the kids of the family (two boys) see the candies. The father has an extra penny. He asks if the candies are “penny candies”. Mae says “oh them, they are two for a penny”. The man gives the penny, the boys take the candies and they leave. One of the truck drivers remark that they were actually nickel-a-piece candies. Then they pay and leave. Mae looks at the money they’ve left, it is half a dollar each, she yells behind them “wait, you have change”, and one of the truck drivers says “you go to hell!”.

Why leave more than twice the money and then “you go to hell” ? What do you think?

Lale

Posted by Dave on 23/3/2002, 6:14:01, in reply to “The Grapes of Wrath”

Lale, I felt the same way as I read Steinbeck’s East Of Eden. Halfway through I realized it would become one of my favorites and it has remained so to this day. He’s quite the writer. Your questions intrigued me, so I reached to my copious bookshelf and dusted off my own, as yet unread, copy of The Grapes. I located the passage about the “$#@%-heels” and the truck-drivers in the diner. In fact, I read all of chapter 15 just to sort-of get a glimpse of the context. Your first question really stumped me for a while… then I got it! I GOT IT!! But… If I Tell You Won’t You Be All Depressed?

The second question is a good one. I read, and re-read that section and I have come to a conclusion (which is only a theory). I think that Bill’s “You go to hell” only makes sense if seen as a continuation of the good-natured banter and joking that preceded it from the time the two truckdrivers entered the diner. For instance, the “seen any new etchin’s lately Bill?” and the joke about the heifer and the bull. It’s all very casual and loose. And there is absolutely no revealed reason that the truckers should say anything rude to Mae as they leave the diner. Quite the contrary. They’ve just observed her softening up to the family of $#@%-heels, and she’s done them a good turn. So I think Bill’s “You go to hell” must be perceived as trucker vernacular for “You keep the change” or “the change is yours Mae.” Similar to a situation where friends may be out for dinner and one grabs the bill when it arrives. As the other offers to pay (for at least his own share of it) the other says “Stick it.” (I seem to recall you and your husband graciously doing this for me once, albeit minus the “stick it” part). The “stick it” is meant as an “I insist” rather than an actual invitation to dispose of the bill in the other’s nether regions. In the case in question, the half-dollars left for Mae show the truckers’ approval of her actions, and their last words are just another way of saying “we’re too familiar for niceties.” Or perhaps to preserve some form of trucker-machismo, Bill quickly resorts to vulgarizing (or downplaying) their own spontaneous generosity. At any rate, I don’t think he would have responded with “You go to hell” if they were still sitting at the counter and Mae had a chance to respond. It’s significant that this was the parting shot, (“the screen door slammed”) and I see it done with a smile on their faces. There is a hint of this mood being understood by Mae herself, because a few sentences later she reflects on truckdrivers in general “reverently”. She has suffered no offense whatsoever. Steinbeck lets us see this going on inside her head to show us that she did not take their “You go to hell” as “YOU GO TO HELL.”

This is my present theory.

I want to comment on your comment of how Steinbeck interrupts his own narration and throws in these brilliant self-contained little pieces. They could be their own little chapters. I noticed this in East of Eden and several pieces were so impressive that they found their way into my NOTWNF (Notebook Of Things Worth Not Forgetting). Please indulge me as I quote in its entirety a passage that I find particularly brilliant. All of a sudden, at the beginning of Part II, the great author broke away for a moment to say the following:

“There are monstrous changes taking place in the world, forces shaping a future whose face we do not know… At such a time it seems natural and good to me to ask myself these questions.

“What do I believe in? What must I fight for and what must I fight against?

“Our species is the only creative species, and it has only one creative instrument, the individual mind and spirit of a man. Nothing was ever created by two men. There are no good collaborations, whether in music, in art, in poetry, in mathematics, in philosophy. Once the miracle of creation has taken place, the group can build and extend it, but the group never invents anything. The preciousness lies in the lonely mind of a man. And now the forces marshalled around the concept of the group have declared a war of extermination on that preciousness, the mind of man. By disparagement, by starvation, by repressions, forced direction, and the stunning hammerblows of conditioning, the free roving mind is being pursued, roped, blunted, drugged. It is a sad suicidal course our species seems to have taken.

“And this I believe: that the free, exploring mind of the individual human is the most valuable thing in the world. And this I would fight for: the freedom of the mind to take any direction it wishes, undirected. And this I must fight against: any idea, religion, or government which limits or destroys the individual. This is what I am about. I can understand why a system built on a pattern must try to destroy the free mind, for that is one thing which can by inspection destroy such a system. Surely I can understand this, and I hate it and I will fight against it to preserve the one thing that separates us from the uncreative beasts. If the glory can be killed, we are lost.”

Is that not completely brilliant? In my opinion, these diversions of his turn his novels into timeless social documents. Thoughtful chronicles of an era. And it’s amazing how he effortlessly turns from these gratuitous essays, shakes his head, and taps right back into his characters with their “getcha” and “gonna” lingo. And with these, he fleshes out the great ideas.

So Lale… “ya dun remindered me to pay more ‘tention to m’ Steinbecks, and gettim’ all readed up!”

~

Posted by Lale on 23/3/2002, 12:20:36, in reply to “Re: The Grapes of Wrath”

: context: Your first question really

: stumped me for a while… then I got

: it! I GOT IT!! But… If I Tell You Won’t

: You Be All Depressed?

IITYWYBAD? If I Tell You Won’t You Be All Depressed?

Somehow it doesn’t make a whole lotta sense along with the other signs though.

: think that Bill’s “You go to

: hell” only makes sense if seen as a

: continuation of the good-natured banter

: and joking that preceded it from the

That was my explanation too. Like “why are you asking, you know it’s for you”.

I also thought maybe, the truck drives being generous and all, they might have been disgusted with Mae’s earlier “loaf of bread” performance and they were just making up for her loss in the candy and bread deal, like “the hell with you, you cannot even give a loaf of bread, I bet that candy money hurts you big, here you go.” But I like your theory and my first instinct better.

: And this I believe: that the free, exploring

: mind of the individual human is the most

: valuable thing in the world. And this I

: would fight for: the freedom of the mind to

This excerpt is one of the most meaningful things I’ve heard in a long time. And he wrote it exactly 50 years ago. So imagine how much worse off we are now on the “exploring mind”. There are a lot of gems like this in The Grapes of Wrath.

Let me correct a tiny mistake though, the $#@%-heels, as you so discreetly spell, are not the likes of that poor family coming in for bread. The $#@%-heels are the rich people, husband and wife, driving expensive cars, buying only a soda for 5 cents and complaining that it was warm. Never leaving any tip. I assume they are wearing nice shoes with high heels, and thus the name.

: “ya dun remindered me to pay more ‘tention to m’ : Steinbecks, and gettim’ all readed up!”

Not bad at all 😉

Lale

Posted by Lale on 24/3/2002, 17:18:50, in reply to “Re: The Grapes of Wrath”

Still have 200 pages to go. I can’t talk or think about anything else. People at home are tired of me going on and on about this book, so I came here to go on and on about it here.

This is not the story of a poor family. This is not about poverty. This is about a system, an indecent system that, coupled with the force of nature, dehumanized people.

They don’t let you work a piece of land even if it is unused, unsown, covered with weeds. You could live off of it if you were allowed to work it, but that would be dangerous for the owners. It is in their best interest to keep their land unutilized rather than let hungry people work it. And that’s only one of the things that’s wrong in the picture.

“And then the dispossessed were drawn west – from Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico; from Nevada and Arkansas families, tribes, dusted out, tractored out, carloads, caravans, homeless and hungry; twenty thousand and fifty thousand and a hundred thousand and two hundred thousand. they streamed over the mountains, hungry and restless – restless as ants, scurrying to find work to do – to lift, to push, to pull, to pick, to cut – anything, any burden to bear, for food. The kids are hungry. We got no place to live. Like ants scurrying for work, for food, and most of all for land.

“We ain’t foreign. Seven generations back Americans, and beyond that Irish, Scotch, English, German. One of our folks in the Revolution, an’ they was lots of our folks in the Civil War – Both sides. Americans.

“They were hungry, and they were fierce. And they had hoped to find a home, and they found only hatred. … “

Even though I haven’t finished the book yet (I have to stop every now and then to think about it, to digest it), I can tell you that Steinbeck can sustain his picture-painting, his vivid descriptions of land and circumstances, and his portrayal of physique and emotions, page after page, without becoming stale, or worn-out. I have never seen such high literary value applied to such an important, meaningful, real subject matter.

Reading the car repair scenes was like watching a movie. I could just see the men working on old, oily car pieces.

Some of the brief parts with Ruthie in it, I re- and re-read them. The interaction between kids is so “exact”:

“Ruthie glared with hatred at the older girl.”

And then a little later:

“Ruthie had stood all she could. She blurted fiercely, “Granma died right on top a the truck.” The girl looked questioningly at her. “Well, she did,” Ruthie said. “An’ the cor’ner got her.” She closed her lips tightly and broke up a pile of sticks.”

Steinbeck writes about the cars, the children, the families, hunger, death, camp, land, cutting meat, cooking, driving, just anything, he can write about anything and when he does, he does so simply and beautifully.

After “The Pearl” and “Of Mice and Men” I had already decided that I wanted to read every book written by this great man. Now, I won’t stop until I do so. Luckily he has written 20+ fiction and a few non-fiction. (I believe the total number of his published books are 25.)

Lale

~

Posted by Guillermo Maynez on 27/3/2002, 2:01:49, in reply to “Re: The Grapes of Wrath”

Lale, this is really an extraordinary book which will move even hard-hearted people. The final scene is sublime.

There’s one interesting character which has appeared by the page you are reading, JC. My copy has a note saying that some critics identify these letters with Jesus Christ, and that the character plays a symbolic role in the novel. What do you think about him?

~

Posted by Lale on 27/3/2002, 14:39:49, in reply to “Re: The Grapes of Wrath”

: There’s one interesting character which has

: appeared by the page you are eading, JC. My

: copy has a note saying that some critics

: identify these letters with Jesus Christ, and

So far Jim Casy has been my most favourite character. I heard about the speculations. I still have a few more pages to go. We can talk about it when I finish. Right now, I suspect Casy will re-appear, and if/when he does, what he says or does might change my current view on it (the speculation, the Jesus connection), so I’ll write when I’m done.

Lale

Posted by Lale on 28/3/2002, 16:03:48, in reply to “Re: The Grapes of Wrath”

Wow! I just finished the book and it’ll take me a long time to shake off its impact.

This is not a sad story, this is not about bad luck, this is not even about poverty. This is about a system. The system has rules, put in place for a purpose. The purpose is to get the cheapest possible labor. At what cost? The system doesn’t care.

It is not one family that starves. It is not a hundred families. It is thousands and thousands of families!

Some readers might have cried while reading this book. I didn’t cry. It was beyond crying. I was filled with shame, and then rage. It is only one story of many of the human species failures.

To write about such controversy without lecturing, or without turning it into a documentary requires a genius. The book is beautifully, *beautifully* written. There are 30 chapters, 15 of them can be taken out of the book and read as independent short stories, or vignettes.

The JC question: Yes, I think there is a lot of symbolism there. Both JCs were searching, they both found an answer and they were both executed when they refused to shut-up.

Jim Casy was a philosopher like Jesus was. His role in the book was not to be a modern-day-Jesus ( “I don’t have a God to pray to” ), but more to demonstrate how the cause-result-solution can be contemplated, achieved. When your thoughts are bigger than the system, the system takes care of you.

Wonderful book. Can’t stop thinking about it. the end was also very symbolic. Who could have thought? What an ending!

I recommend it to every book lover. Read it the first chance you’ve got. Your life will never be the same.

By the way, one American lady from California told me that when she was in grade school, this book was banned in California. I haven’t been able to confirm this but I have no reason to doubt her either. She and her husband were both retired, so I “figger” when she was in school it was maybe the 1945-1950. Does anyone know about a ban in California?

Lale

Posted by Dave on 2/4/2002, 4:36:32, in reply to “Re: The Grapes of Wrath”

Your enthusiasm is infectious, I now want to read my own old dog-eared copy for the first time.

Regarding the censorship issue, your American friend’s information is most likely very accurate. Several month’s after the book’s publication (1939), a St. Louis Missouri library ordered 3 copies to be publicly burned in protest of the vulgar words used by the characters. Similar demonstrations took place in Kansas City and in Oklahoma City. Such censorship reminds me of the very things Steinbeck said he would “fight for”… “…the freedom of the mind to take any direction it wishes, undirected. And this I must fight against: any idea, religion, or government which limits or destroys the individual.”

Steinbeck’s “Of Mice And Men” also came up against heavy opposition from the censors of his own day and age.

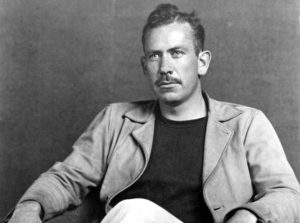

He would have turned 100 on Feb.27, 2002.

~

Posted by Dave on 7/4/2002, 5:22:46, in reply to “Re: The Grapes of Wrath”

Lale, I spent a piece of the afternoon today at the Chapters on Rideau Street, and just happened to pick up a book of Steinbeck’s Collected Letters. As I flipped through it I chanced upon a lot of stuff that was interesting as it pertained to the time of his writing The Grapes Of Wrath.

Apparently, the sheer AMOUNT of the royalty checks for Grapes of Wrath always amazed him. He wrote to his literary agent Elisabeth Otis on April 17th, 1939:

“I don’t think I ever saw so much in one piece before. Well, Carol will squirrel it away for the lean times that are surely coming.”

He had been reading the reviews:

“Do you notice that nearly every reviewer hates the general chapters? They hate to be told anything outright. It should be concealed in the text. Fortunately, I’m not writing for reviewers. And other people seem to like the generals. It’s interesting. I think, probably, it’s the usual revolt against something they aren’t used to.”

And next day:

“Thanks for the check. I don’t expect these things and they are always surprises. The telegrams and telephones – all day long – speak… speak… speak, like hungry birds. Why the hell do people insist on speaking? The telephone is a thing of horror. And the demands for money – scholarships, memorial prizes. One man wants $47,000.00 to buy a newspaper which will be liberal – this is supposed to run on my checkbook. Carol turned down the most absurd offer of all yesterday, to write a script in Hollywood. Carol (over the telephone): ‘What the hell would we do with $5,000.00 a week? Don’t bother us!'”

By June 22, ’39, he is clearly overwhelmed with the publicity of The Grapes Of Wrath:

“This whole thing is getting me down and I don’t know what to do about it. The telephone never stops ringing, telegrams all the time, fifty to seventy-five letters a day all wanting something. People who won’t take no for an answer sending books to be signed. I don’t know what to do. …There is one possibility and that is that I go out of the country. I thought this thing would die down but it is only getting worse every day.”

And things DID get worse. By July 20th Steinbeck wrote about the “whispering campaign” against him, telling Elisabeth Otis:

“The vilification of me out here from the large landowners and bankers is pretty bad. The latest is a rumor started by them that the Okies hate me and have threatened to kill me for lying about them. This made all the papers. Tom Collins says that when his Okies read this smear they were so mad they wanted to burn something down. I’m frightened at the rolling might of this damned thing. It is completely out of hand – I mean a kind of hysteria about the book is growing that is not healthy.”

His fears were well-founded. Years and years later, he would write to his friend Chase Horton:

“Let me tell you a story. When The Grapes Of Wrath got loose, a lot of people were pretty mad at me. The undersheriff of Santa Clara County was a friend of mine and he told me as follows – ‘Don’t you go into any hotel room alone. Keep records of every minute and when you are off the ranch travel with one or two friends but particularly, don’t stay in a hotel alone.’

“‘Why?’ I asked.

“He said, ‘Maybe I’m sticking my neck out but the boys got a rape case set up for you. You get alone in a hotel and a dame will come in, tear off her clothes, scratch her face and scream and you try to talk yourself out of that one. They won’t touch your book but there’s easier ways!'”

In October of ’39, he modestly writes Elisabeth:

“Carol is well and rested. And Grapes dropped from the head of the list to second place out here and about time too. It is far too far when Jack Benny mentions it on his program. Altogether maybe some kind of new existence is opening up. I don’t know. The last year has been a nightmare all in all. But now I’m ordering a lot of books to begin study. And I’ll work in the laboratory. I should go out and shoot some bluejays. They are driving the birds badly. Mean things they are who just raise hell apparently with nothing but mischief in their minds. But I’ll wait until Carol wakes up before I start shooting.

“One nice thing to know is the speed of obscurity. Grapes is not first now. In a month it will be off the list and in six months I’ll be forgotten.”

Sixty-two years later we can say “Not quite forgotten John. Not quite.”

John Steinbeck

Posted by Lale on 8/4/2002, 10:48:52, in reply to “Re: The Grapes of Wrath”

Amazing! Thank you so much for taking the time to post these quotes. My favourite is the one about talking and telephones. What I am saying today and everyday (in our cell phone infested society), he has said it 50 years ago.

Did he really think The Grapes would fall into obscurity?

: happened to pick up a book of Steinbeck’s Collected Letters.

I will most definitely buy this book. I am collecting all of his 25 books and one nice “collection of letters” would fit in well with my Steinbeck collection.

: He had been reading the reviews: “Do you

: notice that nearly every reviewer hates

: the general chapters? They hate to be told

: anything outright. It should be concealed in

: the text. Fortunately, I’m not writing for

: reviewers. And other people seem to like

: the generals. It’s interesting. I think,

: probably, it’s the usual revolt against

: something they aren’t used to.”

Those general chapters, as he calls them, must have been an innovation at the time, something that has never been done before. I loved them. They are essential to the story. The technique of writing them outside the narration was brilliant, I thought.

: Carol turned down the most absurd offer of all yesterday, to write a

: script in Hollywood. Carol (over the telephone): ‘What the hell would we do with

: $5,000.00 a week? Don’t bother us!'”

How Carol answers the “most absurd offer” is delightful. But it did, in the end, get made into a movie. Someone else must have written the script. I won’t be able to see the movie until we return back to Canada (I looked for it in Paris, but couldn’t find it).

I am very happy that Steinbeck didn’t sell out the way Nabokov did. Listen to this: We have read Lolita and we have seen the movie with Jeremy Irons. Just recently, one night we were in the video store looking for something to rent and we saw the old, black-and-white version of Lolita. Script written by Nabokov himself (and directed by Stanley Kubrick). We immediately took it home. How dissappointed we were! He has re-written the story!!! Major sell-out. The part of Quilty is played by Peter Sellers, and to give Sellers more screen time, Nabokov has invented new dialogs (or rather monologues) for him. It was the worst movie I have ever seen. How Nabokov hollywoodized his own book! What a disgrace!

Anyway, back to Steinbeck.

: One nice thing to know is the speed of

: obscurity. Grapes is not first now. In a

: month it will be off the list and in six

: months I’ll be forgotten.”

How success can disturb the peace! Most authors are tormented by it. I read an interview with Ian McEwan in Newsweek this week. He talks about the Booker prize screwing up a writer’s life. I will scan that interview and put it in … hmmm… where can I put it? I’ll put it in “Italian” page which is still empty. It can temporarily host the Ian McEwan interview. Give me 15 minutes.

Lale

~

Posted by Dave on 9/4/2002, 3:39:58, in reply to “Re: The Grapes of Wrath”

Lale, I should clarify the title of the book I found, since you’re interested in it. It’s actually called “Steinbeck: A Life In Letters” rather than “Collected Letters”. It’s edited by Robert Wallstein and Elaine Steinbeck. Totally excellent, the way it’s laid out. You can get it in paperback, so I wouldn’t pay the hardcover price. Mind you, I am basically poor! ($$). And cheap. Another very interesting book I saw at the store (I don’t think it is available in softcover, it’s too new) is a book of Steinbeck essays called “America & Americans & Selected Nonfiction.” One of the chapters is his essay called “The Harvest Gypsies: Squatter’s Camps” which details his inspiration for The Grapes of Wrath. The book also has his Nobel Prize lecture in it too, but then, so does the “Life In Letters” book.

~

Reviewed by: Mike Date: 11 April 2003

IITYWYBAD – stands for “If I tell you, will you buy another drink?” and was more or less a sign you’d see in bars or diners.

This book is outstanding. Really leaves ya feelin’ angry about everything that took place. Chapter 25…that’s powerful stuff right there…