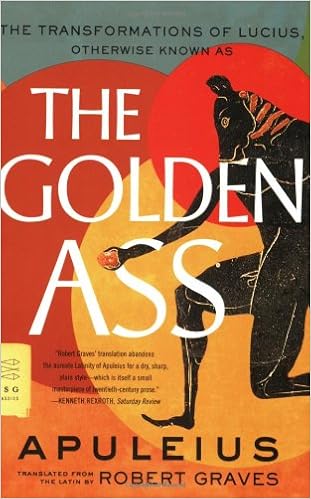

The Golden Ass – The Metamorphoses of Apuleius-Lucius Apuleius

The Golden Ass (The Metamorphoses) – Lucius Apuleius – late second century BCE

Reviewed by: Dave Date: 15 January 2002

A Fantastic Four-Footed Fable

I thought only cats were supposed to have nine lives, but this donkey has at least that many. This book is great fun, I couldn’t put it down for too long, and it is incredible that something written so long ago (18 centuries?) can be so accessible, captivating, and hilarious to a modern reader. The events in The Golden Ass resemble the ribald, bawdy exuberance of the Decameron, and no doubt Boccaccio was somewhat inspired by the writings of Apuleius. According to the introduction, the adjective “golden” in the title implies “the ass par excellence” or “the best of all stories about an ass.” The story follows the misadventures of Lucius, an enterprising young man who gets far too close to the world of magic, is transformed into a donkey and is constantly thwarted in his attempt to procure the antidote to his assness. It’s human mind… trapped in donkey bawdy! Totally imaginative, classically written, hilarious fun. As a writer, Apuleius was MILLENNIUMS ahead of his time! (Note: my review is based on the Robert Graves translation)

Reviewed by: Michael Sympson Date: 15 September 2001

“… give me a copper and I’ll tell you a golden story …”

Fans use to hail Lady Murasaki’s “Prince Genji” as the world’s first novel. Well, if we don’t count Petron’s “Satyricon” because of its fragmented condition, then Apuleius must be a strong candidate. His book predated Murasaki by more than 800 years. And of course there is extant an even older example – “Chaireas and Callirhoe” by Chariton (some time in the first century BC. or AD.) Not to mention the bashfully lewd novel “Daphnis and Chloe” from the 3rd century. (The most interesting aspect of this book is not the sex – but that the two shepherds can see their animals doing it all the time and still be so completely clueless before the last page.) And experts on Egyptian literature may actually be able to push even further back into the past the advent of the novel as a genre.

So the biblical Joseph story could very well be the retelling of an Egyptian original. All that is needed is the mindset of an urban middle-class, some sort of rudimentary public education, a comparably accessible and inexpensive technology of writing, and a viable network of dissemination. All of this was present in Egypt, millennia before it fell under Macedonian protectorate. On the other hand it is not very likely to find tales of novel length written in cuneiform or in Chinese before the introduction of ink and paper, when text was still singed on bundled bamboo slabs with an iron needle in a painfully slow procedure. I have a suspicion that the very earliest novels had been the promptbooks for professional storytellers on the bazaars and marketplaces.

A suspicion confirmed by Pliny the Younger and shared by Robert Graves who retranslated “The Golden Ass” for the modern reader. He based his hunch on the outlandish and weirdly archaic diction of the original and compared it to oral traditions in Wales, which in Grave’s time was still a living craft. In Grave’s opinion, the Author deliberately emulated and travestied the style of oral storytelling. In the Bible, 1 King 13 might be another example for this sort of thing. In fact we can be pretty certain that Lucius Apuleius of Madaura (124 – after 170) meant to mock an established narrative pattern, and not only because his style is so different from Chariton’s and Petronius’ elegance and lucidity. But the very source for his story was originally written in a trim and witty diction.

The story of Lucius who brought on himself bad luck by starting a love affair with a slave girl and was transformed into a donkey, has come to us in two versions. The other version is by Lucian of Samosata (c.120 – c.190) a Syrian from Antioch, who travelled widely the Empire before he settled in Alexandria. His tale is much shorter and lacks all the intimate touches and folklore we find in Apuleius. The two writer’s outlook on religion couldn’t be any more different. Where Apuleius wholeheartedly embraced pagan worship, the “Syrian Voltaire,” lambasted with equal zeal pagan superstition and religion in any form. Some scholars speculate that Apuleius got the idea for his novel from Lucian. But if we look at the data of their biographies this seems to be not very likely. In fact if anybody of the two could have been aware of the other fellow’s existence, it would have been Lucian rather than Apuleius.

But then again, why should the elegant and cosmopolitan Lucian even bother of taking notice of a comparably obscure Roman writer who lived in the African province? So the inevitable conclusion seems to be, that both authors used a common source, now lost, from the stockpile of Greek pulp fiction or “Milesian Tales” which had been around for at least three centuries. Knowledgeable scholars mention a certain Lucius of Patra. In Apuleius’ hands, despite its episodic structure, this story became a genuine novel. The author used all the narrative ploys and plot cliches available, but he also spliced in materials from his own life, from his travels and spiritual adventures, and presents us with a brew of folklore and biographical detail as the vehicle for a moving story of genuine transformation and penance.

Graves might overdo it a bit when he stresses the moral aspect in Apuleius’ story, but it is true: the protagonist’s transformation is no less genuine and moral as the conversion story of St. Augustine, who had read Apuleius, before he composed his “Confessions.” The difference however speaks volumes. As practically every Christian apologist in Antiquity, the African saint is utterly lacking in humor, thus following the great example of the bible itself. The pagan Apuleius, on the other hand, has no such inhibitions, and invites us to laugh with him, even at the gods. This is good pagan tradition. Just recall the unbelievably uncouth obscenities and ribald insults, which such undoubtedly conservative and deeply religious author as Aristophanes, was capable of throwing at the deities.

In a different time and under a different religion it would have meant a public barbecue of the author on a slowly turning spit. But in the liberal atmosphere of Athen’s democracy and pagan laissez-faire, nobody batted an eyelid. The “Golden Ass” though not quite so ribald has its moments too, moments that carried over into Boccaccio’s “Decamerone.” But the allegorical bedtime story of “Amor and Psyche” is recognized as a marvel of its kind. Adlington’s Elizabethan translation is still interesting, but surprisingly a bit coy on the sex; Graves’ translation remains a reliable staple, J. Arthur Hanson’s new rendition in Havard’s Loeb Classics is accurate and elegant – none of them reproduces the rough edges of the original. But it is a remarkable fact that all early translations into French, German, and English had become landmark events in the development of elegant writing.

Apuleius was a magician – in more than one respect.

Posted by guillermo maynez on 10/5/2013, 13:26:07

Well, there’s an image from my childhood: the picture of a man lowering his head to drink from a river, and as he does so, a wound in the neck opens up and the head falls to the water as a torrent of blood rushes from the open gash. It was right there in the “Golden Book for Children”, an illustration of a horrifying tale, the tale of a guy who finds an old friend on the street, and of the story of this man and what happens to them when they’re sleeping at a hostel. It was an abridged version of “The Golden Ass”, and I marvel at the fact that children’s books included those scenes. Years later I read the whole story in a full version translated into Spanish (which is probably easier than to translate it into English).

And now, Robert Graves’s wonderful translation has given new life to this amazing tale. The first emotion aroused by it is the unique opportunity to take a look at everyday life in Roman-dominated Greece, nineteen centuries ago. Of course, every work of fiction allows us to peek into secret chambers, thoughts and feelings; into distant places and times, but seldom has a reader the chance to explore life in so distant a past. This is the only novel (and I think it is perfectly right to call it that in full) from the Latin language when it was alive.

There are a lot of religious, ethical and philosophical undertones in the text, sure, but I first want to emphasize how funny and relaxed the tale is. It is clear that at least the Spanish and Italian picaresque tales from the Renaissance and the Baroque are direct heirs to this style, and fortunately so. Lucius is a funny and smart guy, and all his irresponsibilities and juvenile misdemeanors seem to be entirely justified by his charm.

As I read, I couldn’t help but mourn the absolute loss of the Hellenistic world: the absence of an encompassing ecclesiastical authority and a prudish morality certainly made for a far freer and happier world than what happened after the triumph of Christianity, that grim, sorrowful religion which, for all its virtues in preaching forgiveness, love, and pity, ultimately ended up creating a corrupt Church in the freewheeling clerical environment of the Middle Ages that finally provoked Luther’s indignation and the Reformation. Someone might say: “hey, and what about all that sorcery and superstition?” Well, that at least wasn’t improved by the triumph of Christianity, and even today, centuries after the Enlightenment, people believe in horoscopes, feng-shui, psychics, etc. So, woe to bygone Paganism! A free market of deities! By the way, it seemed clear to me that by Lucius’s time, not only philosophers but most educated people didn’t believe seriously in the Greco-Roman gods, which were more like pieces of folklore. Otherwise, Apuleius wouldn’t have dared to tell the wonderful story of Cupid and Psyche the way he does.

~

Posted by Sterling on 17/5/2013, 16:23:31, in reply to “Re: The Golden Ass and Omon Ra”

Although obviously much less realistic than Njal, I agree that The Golden Ass gives us a charming window into 2nd century Hellenistic society. I also agree that it may be properly termed a “novel,” although it is certainly picaresque. I wonder if the Spanish and Italian Renaisance and Baroque writers of the picaresque had direct access to The Golden Ass (in Latin, of course.)

To some extent, the digressions ARE the story. It is rather like a collection of tales with a framing story.

I agree that it feels like a happier world than, say, the Middle Ages under the yoke of the church. It is funny, though, that it feels sunny considering the amount of horror, violence, sadism, kinky sex, and black magic in it.

It is a sad thing how judgmental, prudish, and moralistic the Church became. I just finished reading all four gospels for a class, and it is remarkable how tolerant and non-judgmental Jesus appears in the portrayal by all four evangelists. (Who incidentally turn out to be much more sophisticated conscious artists than I ever realized.) Of course, the influence of St. Paul is something else again.

~

Posted by guillermo maynez

You’re right. The Hellenistic era, at least as depicted by Apuleius, is sunny IN SPITE of all the horrors that go on. But somehow, the feeling transmitted is of a freewheeling, morally and emotionally relaxed age, taking life as it is and not according to some glum dogmas and guilty anxieties, as instilled later by the Church.

As for Christianity, I’m pretty sure most of us who have issues with religion have them in relation to Church(es) doctrine and practice. The central message conveyed by the Gospels is very simple and it’s hard to think of anyone disagreeing with its core beliefs: tolerance, forgiveness, non-judgmental approach to other people and oneself, charity, respect, and above all, Love. It is very sad, when studying history, to see how these simple, constructive teaching became transformed in its exact opposite: guilt, shame, intolerance, violence, hatred, bigotry, etc.

~

Posted by Joffre on 20/5/2013, 11:25:00, in reply to “Re: The Golden Ass and Omon Ra”

The Golden Ass never got any better for me. As Sterling said, it’s really a collection of tales with a frame story. I hate meeting characters and then leaving them for new ones and thinking all the while that the book is supposed to be about Lucius. He is involved in some of the stories, but only slightly.

The stories themselves are sometimes amusing, but they are amusing mostly in a juvenile way. The Tale of the Wife’s Tub in particular reminded me of tales from Chaucer. Everything is f**king and farting.

The frame story held practically no interest at all for me.

Really disappointed by this book. You guys have seen my list of books I especially enjoyed. I’ve never made a list of the books I found most wanting, but this one would surely be on it if I did.

~

Posted by Sterling on 22/5/2013, 19:32:27, in reply to “Re: The Golden Ass and Omon Ra”

Had I known beforehand, I would have warned you, Joffre. I know how you dislike short stories (even more than I do). Naturally a collection of tales is not to your liking.

Humor, from Shakespeare back (including Chaucer), is rarely actually funny to me. The bodily function humor does indeed seem juvenile, today. Just check out movies like “The Hangover” or “Superbad.” It’s the only humor that holds up at all, though. It is based in human constants that are essentailly the same regardless of period. Other ancient humor tends to involve topical satire and requires copious notes to explain the joke. And as everyone knows, explaining a joke kills the humor. :^)

I thought the frame story was pretty interesting, but then I like all that black magic stuff. I also enjoyed having a window into the mystery religion initiations. I find all that ancient ritual appealing. I’m the kind of guy who read The Golden Bough for fun.

I am sorry that you hated it so much it would make your list. I mean, I didn’t enjoy The Cat’s Table or The Slynx, but they are not all-time worsts, by any means.

~

Posted by Joffre on 14/5/2013, 12:46:04

I’m not yet done with the book, but I’ll begin a discussion.

I chose the Ruden translation on kindle, and I don’t like it. It may be very good, but I don’t like it. I find it too up to date if that makes any sense. There must be a good word to name the problem. I’ll provide examples. Somebody tell me the word.

Photis tells Lucius that the witch wife of that guy (I forget their names) is obsessed with some guy who is “just about the finest thing going.”

The band of thieves who steal the ass Lucius chastise their mother, or whoever she is, by saying she just sits around filling her gut with “the hard stuff.”

There is some mention of a “pre fab” tower or some other structure. Pre fabricated housing in Roman times?

Venus tells Psyche to sort out the seeds and then she will “vet” the work.

These are the most memorable examples so far. Perhaps the story was originally written in such language, but I wonder how that could be known about a story so old. I would prefer language that called less attention to itself.

As for the story itself, I’m a bit bored with it at the moment. I don’t even remember who’s telling this Psyche story. What happened to Lucius? I hope to get back to him soon.

~

Posted by guillermo maynez on 14/5/2013, 14:24:50, in reply to “The Golden Ass”

Probably the best English translation is the one by Robert Graves and that is why it is so famous. Graves, in my opinion, manages a difficult trick: to put an old tale in accessible language, without falling in anachronisms like the ones you describe. As I said before, I read it both in Graves’s 1951 translation and in one to Spanish, by Diego Lopez de Cotegana, from c. 1500, which was wonderful for its antique flavor.

Now, I can’t see how “The Golden Ass” can be boring. It has certainly been criticized for its several digressions, “Cupid and Psyche” being the longest by far, but I think they add weight to the story and are very funny. Go on and you’ll see how good the book is.

~

Posted by Steven on 14/5/2013, 22:32:21, in reply to “The Golden Ass”

: I’ll provide

: examples. Somebody tell me the word.

Anachronistic.

That translation sounds terrible! Next we’ll have Venus “unfriending” someone. I’ll now know never to read a Sarah Ruden translation. I just looked at the online previews of some of her other translations. “Darn tootin'” “Hi, Honey!” “content-free” “cheap thrill” etc. Her translation of the Aeneid doesn’t look too bad, but the rest of them are so flippantly modern that the language is more of a distraction than anything else. Maybe a 14-year-old would find it relevant, but I think it’s silly and derogatory.

~

Posted by Steven on 14/5/2013, 22:51:39, in reply to “Re: The Golden Ass”

I read P. G. Walsh’s 1994 translation for Oxford World’s Classics. He has this to say in his introduction about the Robert Graves translation:

“Finally comes Robert Graves’s Penguin version (1950), recently reissued with a forward and some tactful revision by Michael Grant. The poet-craftsman’s enviably supple use of the English language makes this translation attractive to read independently of the Latin, but it is by no means always faithful to the original, and in places seems merely to offer a paraphrase of Adlington [1566 translation]; literary skill and versatility, not exact scholarship, is the primary requirement for the popular success of a translation. There is a disastrous exordium with ‘Apuleius’ address to the reader’, in which the miniature biography which belongs to the hero Lucius is attached to the author; the translation misleads at some points and condenses at others. But the jocose spirit of the original is well captured, and one may confidently predict an extended life for this version.”

~

Posted by Joffre on 15/5/2013, 12:47:27, in reply to “Re: The Golden Ass”

Anachronistic isn’t the word I was looking for. Prefab is certainly anachronistic, but the others are just words or phrases that seem to be hot so to speak. Remember in the early 90s or so when everyone was using the word closure. We had to get closure to put things behind us. Vet is the clearest example of this. I think Ruden is British and perhaps they’ve been using this word longer, but didn’t most of us learn the word during Obama’s first campaign or a little before? As I said, it’s possible that Apuleius wrote in such language, perhaps for some satirical fun, but I’m not sure how we could know that. And it seems all of Ruden’s translations are like this. I agree with Steven that it seems flippant and deragatory.

I finally escaped the clutches of Psyche, but now I’m lost in another story that seems only tangential to Lucius. Frankly, even when I’m with him, he seems only to get beaten.

~

Posted by Sterling on 17/5/2013, 16:02:36, in reply to “Re: The Golden Ass”

First of all, I apologize to you, Joffre, for pointing you toward a translation that you don’t like (and more expensive to boot!). I read a good review and the translation is recent, so I thought it would be the one to try.

Without having read the Ruden translation, I certainly cannot defend it, but I would like to point out that “vet” as a transitive verb meaning to “evaluate” was a British usage until about the 1980s. It comes from horse racing. (Having a veterinarian check out your horse became “to vet.”) It was in more general usage by the 1930s. It may not have seemed to Ruden to be a current catch-word. (One of the quotes given was from a 1936 biography of G.K. Chesterson.) It came to this country in the second half of the 20th century. William Safire wrote an “On Language” column on it in 1980. I think you may associate it with 2008 because Sarah Palin had so obviously not been properly “vetted.”

~

Posted by Joffre on 20/5/2013, 11:14:36, in reply to “Re: The Golden Ass”

Don’t worry, Sterling. I didn’t think there was much to go on in choosing a translation for this book. I figured you read something good. I had tried myself to figure out which translation was best. I’ve actually wanted to read this book for a long time, but could never make up my mind about a translation. I started to order the Graves back in November when the book made our list and you suggested that translation. I guess I read something negative about the Graves translation then; I don’t remember. I normally get Penguin books when I don’t know of any recommended translator, but I think I read something negative about the Penguin translation too.