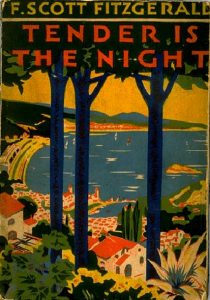

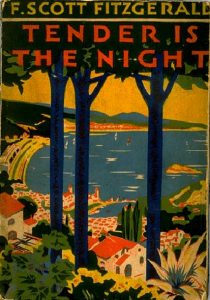

Tender Is the Night – F. Scott Fitzgerald – 1934

Posted by Lareina on 2/5/2004, 23:20:35

I can write for hours and hours on this work – but Fortune smiles on you all tonight for I have exercised some self-restraint and have limited – initially – my comments to what follows.

This disturbing tale of the turbulent relationship of wealthy expatriate couple Dick and Nicole Diver and their blithe existence on the French Riviera illustrates, among many things, images of Americans abroad, corruption by money, mental disintegration, atavistic attraction to charm and sexual jealousy, and loss of the father. Fitzgerald’s brilliant prose, though at times over-dramatized, doesn’t stop short of making us wince in pain as we witness Dick struggle with Nicole’s hysterical fits, his sexual obsession with Rosemary (“Do you mind if I pull down the curtain?”), and his professional demise caused by (or leading?) into alcoholism.

I selected this book based on my interest in the representation of mental illness in literature, specifically when a female character afflicted. Nicole is a diagnosed schizophrenic (p. 128), theorized to be a direct result of an incestuous relationship with her father, and as we are first taken in by her beauty and unassuming charm, we also eventually catch glimpses into her psychotic states and her delicate mental constituency even after her release from the Swiss clinic. Nicole’s journey is a remarkable one, from her studied elegance on the beach at Gausse’s hotel, her crazed episode on the Ferris wheel to her passionate affair with Barban; it is warming to feel her triumph in the end, choosing to surpass even the one who “cured” her.

The loss of the father is by far one of the most striking themes in the book. Mr. Warren’s teary confession to having had sexual relations with his daughter

“We were just like lovers — and then all at once we were lovers…” and Nicole’s immediate reaction ” … never mind, Daddy. It doesn’t matter … ” (p. 129) set the stage for what appears to be an Electra complex (in Freudian theory, a woman with an Electra complex is secretly in love with her father and may even continue her search for ‘the father figure’). (I, however, will not imply that Nicole initialized the incest – she is not to blame here). Dick for Nicole is both her husband and caregiver — her father’s replacement after his violation. Rosemary’s father is also absent from her life, and the irony is that the title of the film that launched her into cinema stardom is entitled “Daddy’s Girl,” (although isn’t her relationship with her MOTHER strange?) a film that she imposes on Dick. Questions along these lines:

1. Do you find it strange that the children, Lanier and Topsy, don’t call Dick “Daddy”?

2. How does Dick react to his own father’s death? (p. 203)

Many of you are aware of the personal weight this book carried for Fitzgerald, as this story almost parallels his own. In this context, we can observe that this book is a dramatized account of his attempt to “save” his wife Zelda (who, unlike Nicole, was never cured of her mental illness and died tragically in a fire in an insane asylum eight years after Fitzgerald suffered a fatal heart attack at the age of 44 — apparently their lives were steeped in personal tragedy).

More questions:

1. What image does Fitzgerald give us of Americans abroad?

2. Does Dick seem particularly American to you?

3. Think of Dick and Nicole’s infidelities, with Rosemary and Barban, respectively. In what are they rooted and how do they differ?

4. Said of Nicole by Kaethe, Franz’s wife: “I think Nicole is less sick than any one thinks — she only cherishes her illness as an instrument of power … ” (p. 239)

To what extent do you agree with her?

5. ” … For Doctor Diver to marry a mental patient? How did it happen?” (p. 156)

Why do you think Dick forfeited his career to be both husband and doctor to Nicole? And was he wrong?

6. How does this book characterize the field of psychiatry?

Posted by Lale on 4/5/2004, 9:35:37

I love Fitzgerald’s style. The Americans abroad (in 1920s) was not something I knew a lot about. I appreciated the glimpse, the window into their lives (however sparcely decorated the rooms of their lives might be). But “Tender is the Night” was nowhere near the greatness of “The Great Gatsby”, and that’s my final answer.

One question to add to Lareina’s list: Did you get the feeling that there were hardly any French in France? Wherever these people went, they bumped into Americans or Brits. It was like Paris and Cote D’Azur were colonies of United States.

Lale

Posted by Chris on 26/4/2004, 20:34:55

I’m not sure I’d say that I ‘miss’ this book exactly, but I did really enjoy it.

It was a bit difficult to get a handle on exactly who or what the book was about; the first half seemed to be primarily about Rosemary’s romantic foibles, but eventually as more about Dick, and the slow unravelling of his world and his marriage. I liked how Rosemary became less and less central to the story, just as she was a symptom of the problems in Dick and Nicole’s marriage, but not really the cause. I wondered about the message here – is it that people sometimes enter into relationships with the right intentions but for all the wrong reasons, or that all relationships, no matter on what basis they were begun, are destined to change and not always for the better?

Some questions came to mind that I’d like to pose to the group:

Why do you think Dick was unable to deal with his fading marriage and infatuation with Rosemary? He was so in control when things were good, but then later could not face the new realities in his marriage.

Did anyone else think that Rosemary’s attraction to Dick was a bit Oedipal? In a way, didn’t Dick replace fathers for both women?

What was it that brought about the change in Nicole, from being comfortable and resigned to suddenly having the courage to leave Dick? Was it just her knowing that Dick had lost interest, or was there else?

Speaking of Nicole, she was by far the most interesting character in the book, partially because we never really saw the story through her eyes.

Posted by Anna van Gelderen on 5/5/2004, 7:42:19

Lareina, what an excellent introduction to an interesting and complex book. You are right, there is a lot going on about fathers – and it did strike me as odd that Dick’s children called him “Dick” instead of “Daddy”. Maybe something to do with his role towards them? He acts more the father towards Nicole than to their children – which is of course an interesting reversal of Nicole’s father acting towards his daughter as her lover.

Nicole is probably the most interesting character because she is painted in such ambiguous tones, and because – as Chris pointed out – we hardly ever see things from her perspective. Lareina already drew our attention to this ambiguity in Nicole by quoting Kaethe: “I think Nicole is less sick than any one thinks – she only cherishes her illness as an instrument of power ….” I find it hard to tell whether Kaethe’s observation is correct, but the fact is that there is something very manipulative about Nicole and that from the beginning she is repeatedly described as “hard”. I get the suspicion that but for the tragic incest affair and her illness Nicole would have been as vapid as her sister Baby. Her greatest talent seems to be the ability to buy a lot of very expensive things in one afternoon.

Fitzgerald does not give a very flattering image of Americans abroad. Most of his charaters seem to be either empty-headed thrill seekers or mercenary cynics. I did not really like any of them, but (and that’s the writer’s art) I did feel very sorry for several of them. Their lives seemed so sad and directionless, so wasted. Even Dick’s dedication to Nicole in the end seems mainly an excuse for not having to work on his science, thereby avoiding the risk of being exposed to the medical world as mediocre – which I don’t think he is. Unfortunately Dick seems to lack substance; he desperately needs to be loved, and this seems his main drive in life. With his charm and Nicole’s money he is very successful at it for several years. But then Rosemary upsets the delicate balance and things slowly go downhill for him.

By the way, what did you think of Rosemary’s mother? She is described as a nice, pleasant woman, but her attitude towards life is completely amoral and utterly mercenary. She very efficiently uses Rosemary’s looks to ensure her daughter’s future (she is a good mother), and then gives this teenage daughter permission to start a little affair with a married man, because it will a useful experience. What a horrid woman.

Coming back to Nicole: do you think Nicole is in love with Tommy Barban, the guy who kills people for a living? Or is he a useful substitute for Dick, who is going down the drain with alcohol and losing it?

~

Posted by Lale on 5/5/2004, 10:49:59

: and then gives this teenage daughter permission to

: start a little affair with a married man, because it

: will a useful experience. What a horrid woman.

Yes, she says to Dick: “I told her to go ahead.”

I don’t think Rosemary’s mother is any different than all the mothers of all the child stars. There is something about these people. It is either living vicariously through their children or for unconcealed desire for money/fame, they make it their full time job to take their kids from audition to audition and put all their means to the service of the promotion of the kid. Then, when these children grow up, if they are a success then they say that their mother (or both parents) sacrificied everything for them and that they are grateful (see Charlize Theron at the Oscars), or, if their fame is limited to childhood and they find themselves grown up without a job, without friends, lost fame and lost childhood, then they say that their parents ruined it for them, not allowed them a normal childhood and now they have nothing to show for it and it was all the parents fault (which it is, of course).

: Coming back to Nicole: do you think Nicole is in love

: with Tommy Barban, the guy who kills people for a

: living? Or is he a useful substitute for Dick, who is

: going down the drain with alcohol and losing it?

This was either the weakest point in the book or I missed something. It was plausible for Nicole to have an affair with this killer guy (who has zero charm for the reader) but it was not plausible that she would leave Dick for him. I am convinced that she is not in love with him, so I would answer “substitute” but he is not a very good substitute either. I was very puzzled to see at the end that Nicole has actually married him and settled down with him. Imagine having your kids growing up in a home with this Barban person.

I think Dick was a good father for the kids. Or at least an OK father. He loved them, that was evident. So, it was strange to see both Nicole and Dick to give up on this father-children relationship so easily. Dick didn’t fight for them, just left. And Nicole didn’t think this was a big loss for the children either. I must say I did not see this coming. The end puzzled me more than anything else in the book.

This Tartan or Barban person was so unlikable. Recall the duel. After it is all over (nobody’s hurt, everyone’s dignity is saved to some degree), he was not satisfied. He wanted to do it over again so that he could actually kill the guy.

And what about the barber scene. It was perposterous. It would have been hilarious if all the parties involved didn’t take it so seriously. Dick and Nicole leaving the barber shop with half of their hair done … Tommy always speaking for Nicole. How could she let him decide on her behalf like that? Not even let her speak to her husband in private, by herself?

“Your wife does not love you,” said Tommy suddenly. “She loves me.”

We haven’t actually seen any evidence of that. She slept with him, yes. But how can he assume this was sufficient to barge in and announce “she doesn’t love you, she loves me.” Nicole allows this. I was expecting her to say “Who the hell are you? What the heck are you talking about? How dare you?” She lets it be imposed on her whom to love and whom not to love anymore.

“I stand in the position of Nicole’s protector until details can be arranged.”

Nicole lets one protector to be replaced by another, and in my opinion an inferior one. I would have liked to see her not needing a protector anymore. Yes, divorce Dick (“It was never the same after Rosemary.”), but build a better life, don’t go under the thumb of this obnoxious man.

Nicole betrayed me as a reader.

Dick betrayed me as well, not because he became an alcoholic but because he gave up on the children (and on Nicole) too easily.

Lale

Posted by len. on 5/5/2004, 11:06:34

Lale responds to Anna:

>I don’t think Rosemary’s mother is any different than all the mothers of all the child stars

>It is either living vicariously through their children or for unconcealed desire for money/fame, they make it their full time job

I think Lale’s got this right. By “looking out” for Rosemary, Rosemary’s mother was looking out for herself.

Remember, Rosemary’s all of 18 years old at the time. BTW, where is Rosemary’s father?

>This was either the weakest point in the book or I missed something. It was plausible for Nicole to have an affair with this killer guy (who has zero charm for the reader) but it was not plausible that she would leave Dick for him.

I may have an unfair advantage here, having also acquired a “reader’s guide” to the novel, but my superficial review of it seems to suggest that this novel began in quite a different form, and that Barban may be a leftover from the original conception that Fitzgerald was unwilling or unable to leave behind.

I’m still only halfway though the book, but I am struck by Fitzgerald’s sloppiness with details (errors of fact that could easily have been corrected without in any way adversely affecting the story), and the occasional utter opacity of his prose. Repeatedly I find myself rereading a passage only to conclude “I have no idea what he’s trying to say”. Perhaps these are manifestations of Fitzgerald’s “writing under the influence”.

len.

Posted by Anna van Gelderen on 5/5/2004, 11:28:34

: Nicole lets one protector to be replaced by another,

: and in my opinion an inferior one. I would have liked

: to see her not needing a protector anymore. Yes,

: divorce Dick (” It was never the same after

: Rosemary. “), but build a better life, don’t go

: under the thumb of this obnoxious man.

: Nicole betrayed me as a reader.

: Dick betrayed me as well, not because he became an

: alcoholic but because he gave up on the children (and

: on Nicole) too easily.

One half of me agrees with you and is disappointed as well. The other half feels that the ending only confirms my suspicion that these people’s strength of character is inversely proportionate to their wealth (Nicole) and their charm (Dick). I can’t quite decide which it is to be. Weird though it may sound, but this is one of the reasons why I missed the book when I had finished it: the ambiguity of the characters. It made them so real and so interesting.

~

Posted by Rizwan on 5/5/2004, 18:07:09

I have a bizarre criticism of the book. For some reason, I can’t stand the names of the characters. They just seem so, I don’t know…plain. Something fake about it, too. I haven’t been able to get over this. I think it kinda reminds me of a soap opera.

I know this is no kind of substantive criticism whatsoever. I must admit, I’ve only just started the book, and my brain is fried sunny-side up having just completed 3 exams, a 50 page paper on US Policy re: Haitian Refugees, and still staring one exam in the face and fearing what it will bring. And I gotta go to work! Anyway, that’s all I have to say for now. Please don’t kick me off the discussion thread for having submitted the worst and most meaningless contribution in book group history.

~

Posted by Lale on 5/5/2004, 20:18:57

Hmm. Rosemary, Dick, Abe, Tommy Barban … You may have a point there.

And I have a critisism along the same vein: What the heck “you are the nicest people I’ve ever met” mean?

Throughout the book, mostly by Rosemary, but by others as well, the “nice people” comment is uttered. They are very nice people. They were some of the nicest people. You are the nicest person. Nice nice nice.

Next time I give a party, I will quote Dick on the invitations:

“I want to give a really bad party. I mean it. I want to give a party where there’s a brawl and seductions and people going home with their feelings hurt and women passed out in the cabinet de toilette. You wait and see.”

Lale

Posted by Lareina on 6/5/2004, 9:17:35

There were several passages in the story during which I imagined appropriate music being played for each scene – for example, nice jazz during the party scenes. If you could concoct a Soundtrack to Tender, what would be on it?

LL

~

Posted by Rizwan on 6/5/2004, 13:49:03

I might start off with a couple of the tracks from Andre 3000 on the latest Outkast album. The passion, sexual obsession, and utter craziness of that disc kind of mirrors the characters in Fitzgerald’s book. And both are very creative and imaginative works.

Ok, I’m only kidding…

~

Posted by Lareina on 5/5/2004, 22:54:14

Rizwan,

I think you hit the nail on the head; let’s examine why.

We would attribute “superficial” and “cosmetic” to standard issue soap opera characters, right?

I think Fitgerald is underscoring the collective blandness of the expatriate set with his selection of names – they might well be named “Fern” “Basil” and “Bob.”

(And I really hope that there isn’t anyone in the group who just happens to go by these names)

Lareina

Posted by Rizwan on 6/5/2004, 11:36:02

: I think Fitgerald is underscoring the collective

: blandness of the expatriate set with his selection of

: names – they might well be named “Fern”

: “Basil” and “Bob.”

: (And I really hope that there isn’t anyone in the group

: who just happens to go by these names)

Actually, certain of my friends do call me Basil, but I digress…

I think you make a good point about his choice of names, Lareina. I hadn’t thought of that angle. Though I wonder if this choice was done deliberately, to underscore the theme of the book as you said, or if he had already begun, by that time, to develop his (failed) Hollywood screenwriting mentality. Probably you are correct, but I do wonder…

BTW: I read somewhere, maybe Amazon, that Fitzgerald died while eating a chocolate bar and reading a newspaper. Aside from how young and unhappy he was when he died, this is not a bad way to go, really. Though I might exchange the chocolate bar for a nice cup of coffee. Something about coffee and newspapers, they just seem to go together.

Posted by the bunyip on 10/5/2004, 17:15:35

Although a bit belated here, your comments on Tender interest me for various reasons. Some fleeting thoughts occur to me.

The portrayal of “the Americans” of those years has been a problem for many. Without the horrendous numbers of casualties or the intense social disruptions suffered by the Europeans, America didn’t experience the Nihilism that swept the Continent in the interwar period. Fitzgerald depicts the anaemic imitation of it these self-proclaimed victors felt. These people innately sensed a let-down from the era of Grand Tours of the 19th Century. Then, there was a growing respect for Continental traditions which was smashed by the Great War. A sense of cynicism replaced that respect.

The actions of Nicole over Barban has deep evolutionary roots. Females of many species, primates and felines in particular, often allow a “new” male to overwhelm what we would call “common sense”. A male showing signs of greater fitness can displace a current mate, sometimes with surprising ease from our view. Lions, chimps, langur monkeys and others allow the replacement males to kill infants, particularly nursing ones, in order to bring the female into estrus. Humans aren’t exempt from such situations, although the individual reactions vary. We really aren’t that remote from the rest of the animal kingdom, as much as we wish to believe otherwise.

Fitzgerald wouldn’t have known of this, of course, but he portrays it admirably. We think we can sit in judgement of such actions, but that’s a false position. Until we understand it better, we should view the literature dealing with such behaviour at some distance.

the bunyip

Posted by Meg on 7/5/2004, 9:04:51

: Coming back to Nicole: do you think Nicole is in love

: with Tommy Barban, the guy who kills people for a

: living? Or is he a useful substitute for Dick, who is

: going down the drain with alcohol and losing it?

I think perhaps we need to evaluate what Nicole’s relationships to people are before we can label them. Specifically, her conception of “love”.

The most important man in her life was undoubtedly her father — from him all other relationships stem. His love for her contrasted with his abuse of her is something that is never really addressed, either by Fitzgerald or by any of the characters in the novel. I got the feeling that, out of some Victorian-era delicacy and “good manners”, not one of her doctors had ever asked Nicole to confront this aspect of her past. Looking at this from the outside, how could she possibly lead a normal life with normal relationships to others if this first and horrific betrayal is never addressed?

We accept without question her love for Dick (which does contain elements of Electra and the eternal search for a father figure she can trust), but that relationship in itself is problematic. Nicole fell in love with Dick through a series of letters she wrote to him during her first illness. In these letters, she was able to make him up, imagine him into being: he became the voice of sanity outside her current situation, the dashing soldier off in foreign places, a mystery and a father figure. Quite intoxicating, I would imagine.

And then he returned, and life progressed, and 10 years later they are still married. Not happilly — no one could ever look with envy on their life of walking on eggshells — but with a great degree of outward stability. They are The Divers.

Mutual dependance, and a fair degree of enabler/addict behaviour — but not a story-book version of love.

In Dick’s infatuation with Rosemary, I think we see how little there is holding the Divers together. If Rosemary were a person of any substance, or any deep interest, it might be different, but as she stands, she is merely a pretty face and the promise of youth. Fitzgerald gives us nothing in Rosemary that would cause a happilly married man to even think of stumbling, and yet stumble Dick does. He does not fall in love with a young intelligent woman — he falls for a social cipher who only seems able to talk to him about her love for him.

In the years following that first summer at the beach, it seems that Nicole fades out of the front of Dick’s thoughts. If reminded of her, he will again feel duty, obligation, love — but she seems to slip further and further away.

And then Tommy Barban re-enters the picture. And when he does, he recreates Nicole as a woman to be loved:

“She knew, as she had always known, that Tommy loved her…”

“Later in the garden she was happy; she did not want anything to happen, but only for the situation to remain in suspension as the two men tossed her from one mind to another; she had not existed for a long time, even as a ball.”

I think Nicole’s “love” for Tommy is based, ultimately, on the same things her love for Dick is based on: the promise of escape, the feeling of having outgrown her current surroundings, and the safety of having someone to take care of her. It is “love” in a way — the only way Nicole seems capable of — but it is also a substitute for Dick/her father, and the exchange of one form of security for another.

Tommy also has the allure of being hopelessly in love with Nicole — something that Dick never was. To a woman who has begun to feel as though she “doesn’t exist”, this might be perhaps the strongest draw of all.

It would be unconvincing to me if Nicole were to stand on her own two feet and declare independence. Nothing in her history has led her to that point — and nothing in her society would make that alluring — Baby is standing alone, but would anyone want to emulate her? Perhaps, if and when she breaks from Tommy, she will find that part of herself.

I do feel, as Lale does, that Nicole betrayed me as a reader because I wanted more from her, but I also feel that she remained true to who she was. For her to have achieved the independence I wanted from her would have been radically unjustified by the character Fitzgerald had created.

Posted by Anna van Gelderen on 8/5/2004, 10:11:48

That’s a pretty impressive analysis, to which I don’t think I could add anything. You seem to have stunned everybody into silence 😉

Anna

~

Posted by Meg on 8/5/2004, 11:03:44

: That’s a pretty impressive analysis, to which I don’t

: think I could add anything. You seem to have stunned

: everybody into silence 😉

: Anna

Thanks.

It was a clever ploy — I just waited everyone out…

(you turn your back for two days here and an entire discussion whirls by…)

Meg

Posted by Lale on 8/5/2004, 12:24:58

What was the deal with the father coming to town, being in his death-bed and then dissappearing? What was the point of all of that? What did it add to the story? Just to remind us of the unresolved, unaddressed father-daughter past? Or did it serve a better purpose?

I was led to think that something terrible was going to happen. With Kaethe prematurely (and maybe a little viciously) informing Nicole that her father was nearby and dying; and Nicole immediately leaving to go and see him. I was expecting either a resolution or a tragedy, but none happened. The father disappeared and nobody ever spoke of this incident again.

Lale

Posted by len. on 10/5/2004, 8:13:39

I had the same question. I’m almost finished with the book (finally), and I have to confess, I doubt I will read any more Fitzgerald based on this. Only Book 2 impressed me as well written. Book 1 was OK, but Book 3 seems like it was just pasted together from leftover odds and ends. I don’t much care for these people (is there one sympathetic character in this novel?), and I’m not sure what it is that Fitzgerald is trying to say. That the idle rich are, well, idle and rich? Got it.

What am I supposed to feel about Dick, who regards his Yale education as a waste of time, and whose commitment to psychiatry seems paper thin? Idle, and rich. Well, his wife was rich.

I don’t know, this novel really seems like the worst form of self indulgence.

len.

Posted by Lale (posting Bunyip’s review) on 26/5/2004, 10:47:16

North America escaped the wave of Nihilism that beleaguered Europe after the Great War. Although escaping the horrendous casualty lists of the European nations, Americans aped Continental disillusionment with their own, anaemic version, of it. Retaining greater resources, America’s wealthy survivors returned to Europe, filled with cynicism and indifference. Few books have caught the attitudes of interwar Americans as vividly as this one. It is a Judas kiss in depicting America’s social values of the time. Few could enjoy the life he describes, yet all aspired to it. Fitzgerald caught and portrayed the segment of that society most people seem to remember. It’s a limited view, but tightly focussed.

Richard Diver, married to what was then termed a “neurotic” woman, encounters a young movie star. Films were still silent and actresses were chosen for their physical appeal. Rosemary, although still a teen-ager, fills the image perfectly. Immature, notorious and vivacious, she sets her sights on Diver. Encouraged by her mother, although the motivation for this remains unclear, Rosemary applies her wiles on a man twice her age.

As the two encounter, separate and meet again, they interact with members of the expatriate community in France. Fitzgerald portrays most of them through the couple’s viewpoint. The depictions are compelling and evocative, but there isn’t an appealling one in the lot. Diver’s role in the new [then] Freudian psychology gives Fitzgerald a mechanism for exploring the human psyche. The dismemberment of Freud’s analysis by modern studies doesn’t detract from Fitzgerald’s descriptive prowess. Even from this distance in time he remains a writer to turn to and reflect on. He’s deservedly acclaimed as one of the “greats” of the twenties. (Stephen, the bunyip)