Posted by Steven on 17/5/2005, 13:26:03

I finished Snow last night. I’ll withhold comment until others are ready to discuss, but I do have some non-spoiler questions for those who are more familiar with the author and the subject matter:

– Are the events in the novel based to any extent on actual happenings in Kars or elsewhere?

– How accurately and fairly does the author depict the social and political conditions at that place and time?

– The novel is set in the 1990’s. How much has the political situation in Turkey changed since then?

– I saw somewhere, perhaps in the Pamuk interview linked from a previous posting, that a quarter of a billion people speak Turkish. Turkey itself is only about a third that size, so where are all the other Turkish-speaking people?

~

Posted by Lale on 17/5/2005, 16:24:39

Hi Steven,

: – Are the events in the novel based to any extent on

: actual happenings in Kars or elsewhere?

Kars is a real city, at the East (North East) of Turkey. Events are fiction, implausible fiction.

People of Kars, the real people, today, hate Orhan Pamuk. So, apparently they don’t feel that they were depicted truthfully or in a favorable light. Pamuk, in one interview, tells this story: His translator (the English lady who translated Snow) goes to Kars and comes back with “Everyone hates you over there.” Pamuk himself confesses that he has never been to Kars. He also confesses that he cannot go any time soon because “that would be dangerous”. (From an interview in German: “Heute würde ich nie dahin fahren, das wäre zu gefährlich.”)

The impression I got is that he took some of the “questions” he had for today’s Turkey (he is from Istanbul) and “posed” them in a fictional setting. Unfortunately he gave his fictional setting the name of a real town which he has never seen and that’s what makes it so unrealistic.

It seems he wanted very much to use the K-Ka-Kar-Kars threesome which he must have found cool, phonetically. This is ruined in translation: Ka-Snow-Kars / Ka-Schnee-Kars / Ka-Neige-Kars. This was apparently used previously by an author Pamuk admires, maybe Paul Auster, does anyone else have more info on this?

Kar means Snow in Turkish and coincidentally there is a town called Kars. All he needed was a character he could call “Ka”. To do this he had to invent a name “Ka”. There is, and can be, no such name in Turkish. The town of Kars just happened to be matching his sound game. Of course, he is trying to invoke Kafka’s K.

: – How accurately and fairly does the author depict the

: social and political conditions at that place and

: time?

Not accurately at all.

Our literature is based on critique. Our most beloved authors, poets, journalists, cartoonists criticize the system, the government. Most of them are sent to jails for their criticisms. But the public understood them and stood by them. They found themselves in their books. They associated with the characters. Orhan Pamuk, by contrast, has alienated the Turkish public. There isn’t one decent character (a hero) in any of his books. This is the same in “My Name is Red”. He has a low opinion of Turkish people, or maybe of the entire humanity, I don’t know.

: – The novel is set in the 1990’s. How much has the

: political situation in Turkey changed since then?

Even though he was using the 90s, I think he was actually talking about today. The islamic movement has doubled, tripled, quadrupled in the past 15 years. So, I think what he had in mind was what he saw in today’s Istanbul. I wish he had set his book in Istanbul.

Less than two years ago we had an islamic government, for the first time since Atatürk founded the modern Turkey.

So, things have gone backwards in the past couple of decades. Our biggest problem (“biggest” because it is symbolic of much deeper things) is the headdress, you know, the veil for women. Atatürk outlawed it in government and in public schools (we are a secular state). I think Pamuk tries to tackle this problem in his book.

Of course there are two point of views:

1. Freedom of expression and religious belief. So, if a university student wants to cover herself up in a veil, that’s her business.

2. This is a political stance. It is against our secularism and against the principles of Atatürk and we cannot allow it.

As much as the first one seems to be the right choice, we tend to take a stance against veil since we know that the veil is being used as a political symbol to promote an ideology, and that religious beliefs are being manipulated and turned into political tools, and that women are offered to cover their heads for money. (I for one, know a nurse who was offered money to cover her hair.) It is no longer about freedom of thought, expression and religion. We have to resist the pressures of the fundamentalist regimes.

: I saw somewhere, perhaps in the Pamuk interview linked from a previous posting, that a quarter of a

: billion people speak Turkish. Turkey itself is only about a third that size, so where are all the other

: Turkish-speaking people?

China, Mongolia. Azerbaijan. I’ll have to look up.

Lale

Posted by Suat on 17/5/2005, 16:45:17

Some percentage of population in the former USSR central Asian republics:

Turkmenistan

Uzbekistan

Kazakhstan

Kyrgyzstan

Also there are minorities in Iran, Iraq, Bulgaria, Greece, Albania and Cyprus.

~

Posted by Lale on 17/5/2005, 16:41:12

Kars from wikipedia:

Town in northeastern Turkey with 90,000 inhabitants (2004 estimate), at an elevation 1,750 metres above sea level on the Kars River. It is the capital of Kars province with 350,000 inhabitants (2004 estimate).

Kars is the economical and administrative centre of a vast but fairly thinly populated region. The region is dominated by livestock raising. The city’s industries include the production of coarse woolens, carpets and felts; leather goods; cheese and processed milk.

Kars lies close to Armenia (80 to the east for a closed border point (road and rail), and 200 km north for an open border point (only road)). Erzurum, 250 km west is the closest large Turkish city (road and rail).

Kars is laid out like a Russian city, a result of 40 years of Russian control. Some of the architecture also belongs to Russia’s Belle Epoque style.

The main attraction among Kars’ historical buildings is the Church of the Apostles built in the 930’s by the Armenian king Abbas 1. Today it has been turned into a warehouse. The stone bridge was restored in 1580, but was built centuries before this. The citadel overhanging the river has been rebuilt numerous times, and the present structure was built by the Russians in the late 19th century. An important military station, it is linked by rail and road with the principal Turkish cities.

HISTORY

Early 10th century: Kars becomes the capital of the Armenian kingdom of the Bagratids.

Late 10th century: Ani becomes new capital, taking away from Kars much of its importance.

Middle of 11th century: Kars and most of the Armenian lands are conquered by the Seljuqs.

1205: Comes under Georgian control.

1387: Attacked by Timur Lenk, but remains under Georgian control.

1514: The region of Kars is conquered by the Ottomans, and Kars is incorporated into the empire.

18th century: Besieged by Persian troops.

1828: Kars is conquered by Russian troops, but reverted to the Ottoman Empire with a peace treaty.

1855: Kars is conquered by Russia during the Crimean War, but just like 27 years earlier a peace treaty brings it back to the Ottoman Empire.

1878: A third Russian conquest leads to a lasting change in Kars’ status.

1921: Kars is transferred back to Turkey.

~

Posted by Lale on 22/5/2005, 12:11:26

: I finished Snow last night. I’ll withhold comment until others are ready to discuss, but I do have some

: non-spoiler questions for those who are more familiar with the author and the subject matter:

: – Are the events in the novel based to any extent on actual happenings in Kars or elsewhere?

Hi Steven,

I started the book. After a few pages I saw a couple of things about which I can answer your question above:

— The oppressed girls: yes, this is true. Women of more conservative families, especially in deeper Anatolia, are frustrated under the iron-fist control of the men in their families.

— Suicides: Oppressed young women may find the only escape in killing themselves. No girl would kill herself because she is not allowed to wear a headdress. They would kill themselves because they are forced to wear headdresses, marry old and ugly man, look after their husband’s family, not be able to go to a movie or have access to anything fun… The headdress issue is created by political movements. It is not a girl’s real problem.

— About the girl in the story who kills herself because she is not allowed to go to school with a head-dress:

1. In the story, this girl’s family advises the girl to take her head-dress off and go to school. They are quite accepting of her taking her coverings off to be able to continue with her education. Now, it is unimaginable that a relatively tolerant family’s daughter would want to cover herself up, i.e. oppress herself more as if the limitations on women in her society weren’t enough.

2. In Ankara and Istanbul we have seen thousands of crazed girls at the gates of schools crying, having fits and threatening to kill themselves if they were forced to take their scarves off. So, maybe one of them could really be mad enough to do it.

But it’s a little different in smaller towns, especially in Kars where we see that women have few rights. Girls would be fighting for more freedom, for instance they’d be resisting marriage at an early age to someone they don’t like. They also watch television and see more open, more comfortable lives and they fantasize about such lives. They would be more likely to kill themselves for not being allowed to go to the cinema. I have a hard time believing a girl in Kars would kill herself for not wearing a headdress, it should be the other way round.

I believe this is a weak spot in the book. It is a contradiction that all the other girls are killing themselves in search of a more equal treatment, more open, liberal lives, for more freedom. One girl is killing herself because they ask her to remove her head-dress in school. Doesn’t make sense.

— Wig instead of headdress: As ridiculous as it sounds, this is true. Girls in big cities, when they are asked to remove their headdress to enter school, are wearing wigs to cover their hair. I find this hilarious. If there ever was a religious loop-hole … It’s like cheating on your taxes. Allah has told them not to show their hair to men, so they wear wigs and show fake hair : – ) As I mentioned before, Allah’s intention when he told women not to show their hair must have been to make them less appealing to men, to reduce the temptation of sin. Wigs won’t work, I’m afraid. But, whatever.

Lale

Posted by Lale on 22/5/2005, 12:33:45

Rich families, like the family of the prime minister, send their q-tipped (heads wrapped up, round and round) daughters abroad so that they can study in peace without having to fight to keep their heads covered. One would think that strictly muslim families who want their daughters to go to school with headdress, would send them to other muslim countries, right? Send them to Egypt or Lebanon or United Arab Emirates. No, no, they send them to United States. Right into the middle of “infidels”. Ahh, the hypocrisy!

Lale

~

Posted by Aysun Alay on 22/5/2005, 15:08:14

: — Suicides

Between 1993 and 2000, there was a rash of suicides among women in Batman (not in Kars). Batman is a small city in southeastern Turkey. The suicide rate among women in Batman had increased more than 50 percent during that time. I remember lots of journalists, sociologists went there to investigate what led those women to attempt or commit suicide. I don’t remember any particular case where the reason behind it was head-dress. Since suicide is a sin in Islam, I don’t think religious women (!) prefer it.

This article from the New York Times may help you to imagine how these women’s life were and why they’ve chosen to die.

http://www.library.cornell.edu/colldev/mideast/batmnt.htm

Aysun

~

Posted by Lale on 22/5/2005, 15:36:16

Aysun, thank you very much for the link.

… beaten by her parents for wearing a tight skirt …

The girls are taking their own lives because of, by degrees, religious, conservative, fanatic or backward pressures and torments.

I was right in guessing that most girls in those areas would be more likely to despair because of limitations put on them by their religious families. They are more likely to seek freedom from being covered up too much and not the other way round.

A 20-year-old woman who felt trapped in an arranged marriage …

A mother of five, worn down by the age of 30 from caring for her husband and his first wife and cut off from the outside world …

These are the real suffering Turkish women. These are the people whose freedom we should fight for.

Not the fake worshippers in big cities. They have their “wig” solution.

Lale

~

The Shooting Scene

Posted by joffre on 4/6/2005, 20:54:15

Ka and Ipek seem to sit carrying on their own conversation while a guy yells and waves his gun around and they are only disturbed when he actually shoots the other guy.

Here’s how this conversation goes if I was talking to Ipek.

Joffre narrowed his eyes as he looked over Ipek’s shoulder. “what is it?”, she asked. Joffre nodded his head. She turned to look. “He seems quite excited.” “Yes.” (whatever Ka and Ipek were saying goes here and then…) “Oh shit.” “What is it?” “Don’t turn around.” “What?” “That guy has a gun.” “Oh!” Joffre tried to keep an eye on the man without noticeably staring at him. “Should we try to leave?” “Do you think he would stop us?” “If I was sure that’s all he would do, I wouldn’t hesitate to try.” “What do you mean?” “Well, he might shoot us.” “Why would he shoot us?” “How do I know? He doesn’t look terribly sane to me.”

That was kind of fun, haha.

~

Posted by Lale on 5/6/2005, 13:43:53

Well, I didn’t realize that they saw the gun. I thought they became aware of it only after the shooting.

Ipek = A very nice and popular girls’ name. It means “Silk”.

Ipek’s sister’s name is Kadife, which means “velvet”. I have never heard of that name. Orhan Pamuk is again playing games with names, if one girl is called Silk then why not call the other Velvet.

Lale

~

Posted by Steven on 3/6/2005, 8:57:07

After novels titled White Castle, Black Book and My Name is Red, now in Snow we have a character named “Blue.” Is there some sort of grand colour scheme to Pamuk’s writings? Do these colors have a cultural significance in Turkey that is different than the traditional associations in Western cultures? (That’s assuming that these titles are being literally translated from the Turkish. Are they?)

~

Posted by Lale on 3/6/2005, 11:02:00

: After novels titled White Castle, Black Book and My

: Name is Red, now in Snow we have a character named

: “Blue.”

And in “My Name is Red”, the main character is called “Black”.

“Blue” in “Snow” is another ridiculous name. I can’t imagine anyone having such a nickname. Both “Ka” and “Blue” are awkward, just not Turkish.

Once again Pamuk is trying to be inventive like his Western colleagues but it is not working.

: Is there some sort of grand colour

: scheme to Pamuk’s writings?

He wishes. No grand scheme. Just trying to be original. Just like “Ka-Kar-Kars”.

: Do these colors have a

: cultural significance in Turkey that is different than

: the traditional associations in Western cultures?

Not that I know of. Except for green maybe. Green seems to be colour of Islam.

Red Cross is Red Crescent

(Institute of) Teetotalling is Green Crescent

The flag is red. I think red is not really associated with communism like in Russia, but it is more of a colour of nationalists.

Blue is maybe in relation with the “evil eye” which is blue. There are superstitions and some proverbs/expressions around “blue”. You would make a child wear a blue bead to protect him/her from the evil eye. Things like that.

Out of all the colours, Blue suits the best to a Sheik, but it is still awkward.

: (That’s assuming that these titles are being literally

: translated from the Turkish. Are they?)

Yes, they are.

Did you notice that Orhan Pamuk plugs his previous books in “Snow”? There is “White Castle Cafe”, and there is one other, I can’t remember now, I’ll look it up.

Lale

Posted by Steven on 3/6/2005, 12:49:19

: Did you notice that Orhan Pamuk plugs his previous books

: in “Snow”? There is “White Castle Cafe”, and there is

: one other, I can’t remember now, I’ll look it up.

That would be the New Life Pastry Shop.

~

Posted by Lale on 3/6/2005, 13:06:03

Pamuk is plugging in his books New Life and White Castle, is that a decent thing to do? Just one of his “originality” things I guess.

Lale

~

Posted by joffre on 3/6/2005, 14:05:39

As you might have noticed in one of my posts in the Batman discussion, Nabokov also did this. Lolita is mentioned in both Pale Fire and Ada, or Ardor. I believe Pnin may be mentioned in Pale Fire. Because of the complex structure of Pale Fire, Nabokov goes so far as to joke that you might even want to buy two copies of the book which you can keep in adjacent positions on the table for easy reference back and forth. I’ve not noticed this in Snow. I not familiar enough with the titles of Pamuk’s books. I like this kind of thing though; it makes me smile.

I also think Nabokov might well like the Ka, Kar, Kars business.

~

Posted by Lale on 5/6/2005, 13:50:56

You might have wondered why people are always kissing other people’s hands. This is a Turkish tradition. You kiss the hand of an older person to show respect. Then you put it (the hand you just kissed) on your forehead.

Thank goodness this tradition has almost completely vanished in big cities. when I was a child I used to kiss the hands of all of the friends of my parents, and most relatives’.

Older people give their hand to you with the back facing top, so that you can take it and kiss it and then place it on your forehead.

If you kiss the hand of a person who doesn’t wish to be treated as an old person then you are in trouble. You try to bring the hand to your mouth and they push it down, so you get the message. It’s very awkward. Then, there was the time when this was going out of fashion (in Ankara, Istanbul anyway), that was the most confusing time, you never knew if you should or you shouldn’t. If you didn’t, you could get reproached: “Come here, kiss my hand!”.

My daughter who goes to Turkey every summer, recently asked me how she could know when to kiss and when not to kiss. I said “do as your cousin does”.

Lale

~

Posted by Lale on 8/6/2005, 11:38:10

: After novels titled White Castle, Black Book and My Name is Red, now in Snow we have a character named

: “Blue.” Is there some sort of grand colour scheme to Pamuk’s writings? Do these colors have a

: cultural significance in Turkey that is different than the traditional associations in Western cultures?

Steven,

Last night, I stayed up all night and read an analysis of Orhan Pamuk’s “New Life” and “My Name is Red” (mostly the latter, a book I just read last month) by a Turkish philosopher, political analyst and historian Yalçın Küçük.

He doesn’t talk about the general colour scheme, but he talks in-depth about the meaning of “red”. It is very long so I cannot summarize it here. He goes back to the time of Sultan Murat III (during whose reign “My Name is Red” takes place) and unravels all the keys and hidden messages one by one. It is amazing. I would love to share what I learned with you but to do that, I will either sit down and translate the whole book in English and post it here, or, you will come to Ottawa and we’ll have an Orhan Pamuk meeting (which cannot happen without the participation of Friederike who is just about to finish her Ph.D. dissertation on Pamuk, because I have bombarded her with Pamuk articles and interviews for the past 6 months) and I will open the book in front of me and translate certain passages and we’ll discuss.

Lale

~

Posted by Steven on 8/6/2005, 20:09:24

Of course any author with enough time and cleverness can write a book full of hidden keys and symbols. Whether it is of any value to the reader, either as entertainment or enlightenment, is, however, the more important issue, and the one where I still have mixed feelings about Snow. I’m eager to learn what you think when you’ve finished it.

Steven

~

Posted by Steven on 5/6/2005, 23:44:31

These are some more or less random, late night thoughts about Snow.

As I said in an earlier post, I don’t see Snow as a political novel. It’s theme is Ka’s discovery of his place in the universe, which he visualizes as the centre of the three axes of Reason, Imagination and Memory, making up a snowflake diagram.

Ka decides that snow is God, snowflakes have a hidden symmetry, and God is therefore the hidden symmetry of the universe.

The snowflake has three physical axes, and Turkey has three political axes (Kemalist, Islamist and Kurd).

The symmetry extends to the characters in the novel. Most characters have a mirror image — Ipek and the porn star, Sunay and Blue, Kadife and Funda Eser, etc.

There is also a symmetry between the life and death seriousness of the coup, versus the entire city’s being caught up in a Mexican soap opera. Similarly Ka’s idealized love for Ipek and his fixation with pornography.

Ka moves through Kars as through a dream. He absorbs the views of everyone he encounters, and offers no resistance to their influence. He falls in love with Ipek, Necip, Blue, the Sheik and Sunay. He sees himself as the neutral centre in their lives, unable to make a choice.

In the end, the snow melts, he become disillusioned, loses the centre, things fall out of balance, and nothing about his life has changed as a result of his “revelation.”

So what does it all mean? That’s the real problem with this book. After the theatre shooting, I decided it was all an absurdist drama, a play within a play, and quit worrying about how unrealistic it is. But where does it get us? Like Ka, after this wild ride we’re right back where we started. We, and he, are left with the poignant reflection that there’s a deeper meaning to it all that stayed just out of our reach. Maybe because it was never there at all.

~

Posted by Lale on 6/6/2005, 11:44:11, in reply to “Hidden Symmetry”

Hi Steven,

I did tremendous progress in the book last night. (Joffre, what page are you at?)

I have a lot to say but I am just dreading the task of writing them all up. I wish we could all get together over dinner and discuss all these.

The book must be very confusing for the foreign audience. People don’t know about the “revolutions”, about Kurdish issues … And the author has mixed them all up in a soup, nothing is clear. I don’t understand if the military, in the book, is targeting the Islamists or the Kurds or the communists or the freethinkers like Turgut Bey (“They could come even for Turgut Bey”)?

Orhan Pamuk could have focused on one or two things and he could have written a better book. This is a mess, in my opinion.

Police or soldiers are shooting and killing whoever they happen to see. One guy (Kurdish folklorist who prepares his suitcase for jail) got shot for no reason. This is not a drug war in Columbia. I am outraged. If you are writing fiction then set it in a fictional country.

~

Revolutions: These are not revolutions by the public. Nothing like the Russian revolution or the French revolution. I don’t know why we translate them as revolutions. They are, in fact, military coups. But the public (as Pamuk indicates in the book) supported some of these coups. (They never turned out to be good for Turkey.)

In Orhan Pamuk’s life time, there have been 3 of these coups. In 1960 (as a result, the prime minister was charged with treason and eventually executed), in 1972 (this was not a full blown coup) and in 1980.

Atatürk entrusted the secularity to the military. So, when things go too nationalistic or too islamic (or as in 1980, both) the army steps in.

In 1972, however, it was a different kind of coup. It was against the intellectuals who favoured socialism. All the freethinkers suffered. All writers, journalists were put in prison. That is a time to write about. Orhan Pamuk should have written about that.

Steven, you have written a beautiful review for a lousy book. I think your interpretation of the book is a compliment to the book. I wish I could see the book as you do, your review makes it a valuable piece of art.

Lale

Posted by joffre on 6/6/2005, 22:20:04

Your theory about the absurdist drama is interesting. When I read the scene in the theater, I thought it was like something out of The Master and Margarita.

~

Posted by Steven on 6/6/2005, 23:10:04

: : Your theory about the absurdist drama is interesting.

: When I read the scene in the theater, I thought it was

: like something out of The Master and Margarita.

Supposedly Orhan Pamuk was paying homage to Kafka by naming Ka after “K” in The Trial. The full progression is thus:

K – Ka – Kar – Kars

It’s been many years since I read The Trial, but one review I read said that many of the elements in Snow are lifted directly from Kafka.

~

Posted by Lale on 7/6/2005, 9:41:01

“The Trial” is one of my favourite books. I am sure you won’t be surprised that I found absolutely no similarity or connection between the two books. In one interview I read Pamuk bringing this up and comparing his protagonist to Joseph K. and I was offended. It is blasphemy.

Orhan Pamuk has a huge ego, not a very pleasant character trait. He compares himself to Umberto Eco, to Kafka and even to Voltaire. Please!

In interviews he always brings up a few great names in the hopes that people will start seeing him in the same light. For instance:

“Diese Ultranationalisten hätten mit der gleichen vulgären Haltung und dem gleichen fiesen Grinsen auch Virginia Woolfe, Marcel Proust oder Thomas Mann als Angehörige der Bourgeoisie attackiert. Diese Leute können mir nichts mehr anhaben.”

Maybe Friederike can translate this for us, but from what I understand, he says that Woolfe, Proust and Mann were also misunderstood and attacked, just like him.

I mean, come on. This guy’s ego and arrogance have to be taken down a notch.

I don’t know, maybe they should just give him the darned Nobel Prize and then he will shut up, ride into obscurity. Like Solzhenitsyn, maybe he’ll be never heard from again. By the way, it is a huge coincidence that, in fact, today the world did hear from Solzhenitsyn. He is in my morning paper:

Solzhenitsyn warns Russia of uprising

Dissident predicts Ukrainian-style revolution

Lale

~

Posted by joffre on 7/6/2005, 13:53:11

‘The Trial’ is one of your favorite books? Wow. Although I respect Kafka, and seriously doubt that Pamuk will ever be considered on the same level as him, I find Kafka; outside of, perhaps, The Metamorphosis which is so short; very unpleasant to read. I would rather read ‘Snow’, haha. That said, I am almost sure to reread ‘The Trial’ someday. I respect his reputation enough to put some effort into appreciating him. I feel the same way about Shakespeare, but I’d rather read Kafka than Shakespeare.

~

Posted by Lale on 7/6/2005, 16:30:01

: : ‘The Trial’ is one of your favorite books?

Well, OK, you caught me. Maybe I exaggerated a little bit. It is not in my top 10, but definitely in my top 50.

When I visited Prague – forgive my Pamuk-like attitude but – I thought, if I was born and lived all my life in Prague, I could also write things like “The Trial”. It is a place that inspires the Kafkaesque.

Lale

~

Posted by joffre on 7/6/2005, 17:56:12

Prague is beautiful. Karlov most is pictured on my copy of the Metamorphosis. And I’ve actually been on the bridge. I like that. Schloss Hohenzollern in Germany is the castle pictured on my copy of The Castle, and I’ve been there too.

~

Posted by joffre on 21/6/2005, 14:24:40

What do you all make of the appendage at the end that tells the order in which Ka’s poems were written? As soon as I saw that, I wondered why it was there. I looked at the pages it references and found that specific numbers of lines are given for the first two poems. This made me wonder if they were somehow hidden in the text. I thought first of the chapter headings which are mostly long enough to possibly be lines of poems, but they did not seem to work for me. I didn’t have time to look around more because I had to return the book to the library. Does anyone else think there is anything here? Or am I just still thinking too much of Perec?

~

Posted by Lale on 19/6/2005, 10:00:38, in reply to “Review of Istanbul”

Pamuk’s ideas and suggestions (the ones in “Snow”, some of the ones in “My Name is Red”, some of the ones in his story “Istanbul”, in his interview in Switzerland with “Das Magazin” and in his interview with New York Times recently) offend me, insult my very being and bad-mouth all the principles I believe in. I am done with Pamuk and his writings.

Lale

Posted by Steven on 21/6/2005, 22:14:38

I didn’t think of trying to derive the text of the poems from clues in the list, but I have tried, without any success to make sense of the poems, the snowflake, and the order in which they were written.

The only obvious point is that “I, Ka” is at the center of the snowflake diagram and exactly halfway down the list.

I tried to reason the placement of each poem on the snowflake, either by the topic of the poem, where it was written, or the character to which it relates. None of them makes any sense. Poems relating to Ipek, for example, which I thought would relate to “Imagination,” appear at points on all three axes. Poems about God and relating to Necip, appear at both “Reason” and “Memory.”

I even took the order of the poems and played “connect the dots” on the snowflake to see if it drew some type of symbol or diagram, but no luck — just a jumble of lines that looks like a wrecked kite.

So I go back to my earlier observation — the snow MELTS. The poems get lost. Ka’s attempt to find balance in Kars fails. His discovery that God is the hidden symmetry in the universe, as symbolized by the hidden symmetry of the snowflake, is all an illusion. There’s no quick and easy answer to life’s mysteries. That’s what I get out of the book, but whether this is what Pamuk meant to say is another question…

~

Posted by Guillermo Maynez on 24/6/2005, 14:04:02

First of all, I have to say I liked the book. I will not crush my head debating whether it is a great work of art or not. I simply think it’s a good novel. I know Lale hated the portrait of Turkey that Pamuk presents in his book, but we should always remember it’s fiction. Definitely, I don’t think it can be categorized as a “political” novel. I don’t think it’s about politics at all, but after 9/11 it’s good marketing to say it’s about Islam and current political instability. I concur with those who say that the main subject of the book is Ka’s discovery of his emotional balance, of his place in the world. It’s a very disheartening novel, because in the end Ka goes back to his dull life, replacing porn for love. It’s also a strange book, totally fictitious in the sense that it’s hard to believe what happens in it.

I was confused about time. By the middle of the book it seemed to me that weeks had passed, and much on the contrary we were still in the first day after Ka’s arrival. I can’t believe so many things happened in just three days, but then again, I don’t judge novels by their verisimilitude, but by their aesthetic merit, and I think in that field “Snow” is satisfactory (though of course imperfect).

Somehow I had to feel empathy with Ka, although as a character he doesn’t really come true as a whole. Ipek sounds like the girl to see, but I never developed much attraction to her, beyond her looks (imaginary, as it should be). The sister was totally annoying, with her pose as a model-cum-Muslim fanatic. The Blue character is the kind I’d like to strangle with my bare hands. I hate those ideologues, and violent to boot.

So I wouldn’t say this is a great novel, based on character development, but the story is gripping, tense, fast-moving and interesting.

I’ll probably say more later, but for now suffice it to say that it’s a bizarre novel. The theatrical coup sounds totally unrealistic, and I never understood whose side they were. How come the soldiers supported the lunatic actor? What kind of factions are there supposed to be in the Turkish army? It went over my head.

A final question: has anyone of you read “My Name is Red”?Is it worth it?

Posted by Lale on 24/6/2005, 16:01:49

: A final question: has anyone of you read “My Name

: is Red”?Is it worth it?

I read it. It is a better book than “Snow”. At least there is a story in it. However, the repetition is relentless. Within the first 50 pages of the book, he uses all he knows (all he has researched) about miniature illustrations of the 15th century. The other 350 pages are just repetition, repetition. He repeats how to draw a horse one hundred times. Towards the end of the book I was bored out of my brains and it took me great effort to finish it.

He has put himself (Orhan), his brother (Shevket) and his mother (Shekure) in the book. In real life, his father had abandoned them for several mistresses. So, in the book, his father is absent. He sends the fictional father to war and he never returns, he is “assumed” dead.

The last chapter of the book is narrated by the mother, Shekure. She says “… don’t be taken in by Orhan … {if he} made our lives harder than they are, Shevket worse and me prettier and harsher than I am. For the sake of a delightful and convincing story, there isn’t a lie Orhan wouldn’t deign to tell.”

That’s the last sentence of the book. I agree that there isn’t a lie Orhan wouldn’t deign to tell but I doubt his lies make any of his stories delightful or convincing.

I would not particularly recommend “My Name is Red” but you’ll say that that’s because I’m biased against Orhan Pamuk. In fact, I enjoyed the first 100 pages. It was afterwards that I got bored with the long, drawn-out, repetitive story telling.

In Turkish, this book is unreadable, by the way. It’s incoherent, unintelligible and there isn’t one sentence that is literary, or poetic, or beautiful. The English translation is a huge improvement on the original.

Guillermo, I heard that the Spanish translation was even better. I heard this from a friend who liked this book so much that she read it first in English and then in her mother tongue which is Spanish. She actually met the Spanish translator in person, he was her Turkish teacher. I still say “don’t waste your time, when there are so many other books that are much better.”

Lale

You’ve got poem – Posted by Lale on 24/6/2005, 16:15:58

With respect to Ka’s poems or poem writing, I can’t resist asking this question: Is it only me who thought it was hilarious how the poems were “arriving” to Ka, like the divine revelations (vahiy) coming to Prophet Mohammed from the Heavens? C’mon, it was ridiculous! At one time, he is on the street and as if he was struck by a bout of diarrhea, he rushes back to the hotel to write his poem. At the dinner table:

The maid went further and told me that a light had entered the room and bathed all those present with divine radiance. In her eyes, he achieved sainthood. Apparently someone then said, “A poem has arrived,” …

And, we don’t even get to see these poems that are accompanied with divine radiance. The contents of the poems we are supplied with don’t seem as if they could be parts of a poem. At the end of the book the list of the poems are given. What a joke! Where are the poems themselves? We get to see the titles but not the poems, we just have to assume they are absolutely brilliant since they are blessed with divine radiance. Pasternak didn’t just list the titles of Dr. Zhivago’s poems at the end of his book, he printed the poems themselves.

L.

Posted by Steven on 24/6/2005, 20:06:09

Ridiculous, yes — that sort of thing only happens in the shower! (Well, to me at least, but I don’t get poems, only computer programs.)

But, seriously, the poems are divine revelations. Remember that the snow is falling also, and the snow is God. Ka says so. The snow is God, and God is the hidden symmetry of the universe. The poems that come to Ka are the key to that symmetry, and they fall from Heaven with the snow.

You can carry this even further and find messianic qualities in Ka himself. (If Kar/Snow is God, then Ka is part God.) He goes wandering about, innocent and pure of heart (but not necessarily sober), is made to suffer for his goodness, and receives divine messages from above. In his snowflake diagram, he tells us that “I, Ka” is center of the snowflake: he is the heart of God.

Ka, as God’s avatar, finds Kars a violent, fractious and unchaste place, so he goes back to Germany. Does this mean that Turkey will likewise be found unworthy of entering the Promised Land of EU membership?

Then again, reading this much meaning into Snow may be akin to finding the image of the Virgin Mary in a piece of moldy toast.

Steven

~

Posted by joffre on 23/6/2005, 15:51:17

I enjoyed the brief discussion between Ka and that boy whose name I can’t remember about how people read books. The boy asks Ka not to write anything bad about Kars because people will believe it, and Ka says nobody reads books in that way. Obviously Ka is wrong about that. Many people read books that way, and apparently many have read Snow that way or fear that people will. I don’t read books in this way. I probably separate fiction and reality to a much greater extent than most people. I think i have read that Oscar Wilde said that reality or life provides on the raw materials for fiction. That’s the way I read books even if I am aware that they were written as commentaries on reality or life. Anyway, I think it is amusing that Pamuk foresees the reaction to his book and sort of tries to temper it in this way.

~

Posted by Steven on 24/6/2005, 9:26:54

: I enjoyed the brief discussion between Ka and that boy whose name I can’t remember about how

: people read books. The boy asks Ka not to write anything bad about Kars because people will

: believe it, and Ka says nobody reads books in that way. Obviously Ka is wrong about that. Many

: people read books that way, and apparently many have read Snow that way or fear that people will.

: I don’t read books in this way. I probably separate fiction and reality to a much greater

: extent than most people.

Yes, I think most people, myself included, when they are reading about a place or time they know little about, will tend to form an impression even when they know that what they are reading is fiction. If we had read Snow without Lale as an antidote, I think it would have been hard not to come away without some negative feelings towards Turkey, as I’m sure thousands of readers have already done.

Ka’s Konfusions, August 3, 2005 – by Friederike Knabe

Novels like Pamuk’s “Snow” can be understood at different levels. Consider it as pure entertainment; for the political intrigue and thrill; or as a virtual door into a foreign place, the lives of far away people, their time or preoccupations.

Pamuk has attempted to present us with all three options in one. The reader is exposed to a panoramic view of Turkey’s political and religious conflicts and ethnic tensions. His multitude of characters represents every conceivable strand of Turkish society: Atatürk secularism and pro-European modernism on the one hand and various religious factions of Muslim faith on the other. By compressing the events into one locale, a remote, poor and backward town, Kars, in Eastern Turkey, he creates a charged playing field. A major snowstorm has cut off the access roads to the town, bringing the conflicting positions to boiling point. A couple of murders occur. The mayoral election, which would have been won by an Islamist over a local Secularist, is cut short by a military coup. In addition, the town has become notorious in the Istanbul headlines for several suicides and suicide attempts by the so-called “headscarf girls”. The assumption being that the girls decided to end their life because they were not allowed to wear their headscarf in school. Yet, their motivations are more complicated than that.

Within this complex political turmoil, wanders Ka, the protagonist of the story. A recently unproductive poet, he returned from Germany to attend his mother’s funeral. He has also reasons for coming to Kars. Presenting himself as a journalist, he claims to be interested in the stories behind the headscarf girls’ suicides. On a personal level, he wants to find a “Turkish girl” to marry and take back to Germany. The object of his dreams and desire is Ipek, a young woman he admired during their student days and who now lives in Kars.

The story is told by Orhan, a close friend of Ka, four years after the events in Kars. Orhan travels to the town to retrace Ka’s steps, to find his notebook with the poems and also to shed light on the political dramas of the day. In many ways he describes Ka as a somewhat confused, middle-aged man, whose exposure to the realities of Kars result in his questioning his life so far. He is taking in all political and religious positions, getting increasingly entangled as events unfold. Wanting to please his various interlocutors, he appears to flip-flop his own positions. In discussions with religious leaders he even wavers in his secular beliefs and appears to be overwhelmed by a sudden spurt of poems that come to him as through some “divine channel”.

While going into minute, sometimes tedious, detail in defining time and place, the activities are increasingly repetitive and predictable. The characters, despite being given ample dialogue are not convincing and the rationale for some of their actions seems almost farcical. The newspaper editor who pre-empts the next day’s news headlines, the theatre director/actor and his belly-dancing companion who play leading roles in the secularist movement. Nobody is quite what they want or appear to be. The women, in particular, despite their importance for Ka, are hollow. His love for Ipek is not based in reality but rather on his daydreams, both past and future. Her beauty is praised constantly, but nothing much of her character is revealed.

Pamuk himself described “Snow” as a political novel. Is it convincing in that ambition? For the reader who is not that familiar with Turkey or its language, it is difficult to judge its value in this category. My own interpretation is that Pamuk created a satire on Turkey and its historical and present-day problems. The exaggeration in the description of Kars, political intrigues, religious fanaticism, military brutality, and Ka’s own personality would lead to that assessment.

The narrator, Orhan, interjects his own 20-20-hindsight vision of Ka in his interactions with the other protagonists of the story. Several times, he addresses the reader directly and, halfway through the book, reveals what happens to Ka after his return to Germany. An all-knowing narrator can be an effective technique in a story, but it is not very successful here. Rather than complementing the reader’s understanding, Orhan competes with his friend for their attention. The result is a strange mix of over-detailed reporting on the events and circumstances in Kars during the snow storm and very generalized, almost philosophical commentary on love, poetry, happiness in which the character Ka is embedded. Actually ** 1/2 stars [Friederike Knabe]

Pamuk on Trial – Posted by Steven on 19/12/2005, 23:18:27

Lale’s favourite 😉 novelist, Orhan Pamuk, is on trial in Istanbul for the crime of having “publicly denigrated Turkish identity.”

Here are a newswire story,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/worldlatest/story/0,1280,-5486393,00.html

an editorial,

http://www.opinionjournal.com/la/?id=110007680

and Pamuk’s own comments,

http://www.newyorker.com/talk/content/articles/051219ta_talk_pamuk

~

Posted by Lale on 20/12/2005, 9:18:07

Yes, I have been following the mess.

Indeed, Turkish expatriates have heard enough of it and they, like the rest of the nation, remain divided.

Pamuk said what he said to create controversy. He wanted this. This was all part of the plan. He must be enjoying the situation tremendously. It is all part of a grand scheme to get Pamuk as many “peace” awards as possible, and eventually the Nobel prize. Pamuk is a fraud. He is the product of a very strong lobby group (The New Yorker has been a huge supporter of Pamuk for a very long time now) and everything he says and does has a reason. There is a goal.

Turkish Government: It is no better than the aforementioned. The current administration is set out to eliminate Modern Turkey, the Turkish Republic founded by Atatürk. They want to establish an islamic republic instead.

It is interesting that these two despicable sides are fighting, one being worse than the other, in full view of the world. I cannot defend one or the other, I wish they both went away.

No, there is no freedom of speech in Turkey. There never was. But why didn’t The New Yorker, The New York Times, The French, The Canadian, The German defend Nazim Hikmet or Yashar Kemal when they were jailed? Why choose to defend a phony non-entity who does everything he does to achieve an end, who is a puppet of bigger forces? The man can’t even write a decent book. It is all about connections.

What a mess.

Lale

~

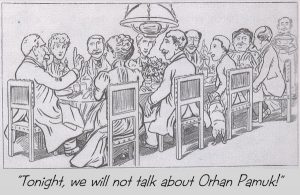

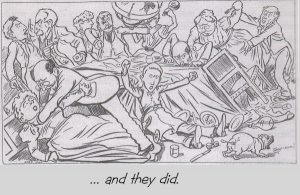

Turkey’s Dreyfus affair – Posted by Lale on 20/12/2005, 9:53:05

In a French history book, I saw a delightful cartoon called “A Family Dinner”. It was by Caran D’Ache illustrating the furious disputes engendered by the Dreyfus affair (early nineteen hundreds). Last year, when Turkish intellectuals were divided over “The Pamuk Affair”, I adapted this cartoon to reflect some of our dinner parties:

“Surtout! Ne parlons pas de l’affair Dreyfus Orhan Pamuk!”

“… ils en ont parlé …”

~

Posted by Lale on 20/12/2005, 10:10:30

The irony is that the government and Pamuk who are at loggerheads, actually have a lot in common:

1. Orhan Pamuk likens himself to his protagonist Ka (“Like Ka, the hero of my novel Snow, … “) who visits a sheik and kisses his hand. The government supports and encourages sheiks.

2. Orhan Pamuk belittles Atatürk and he is clearly against his reforms. So does, and is the government.

3. Orhan Pamuk yearns for the past, longs for the days before the Republic was founded. So does the government. They try to bring back the olden days when women couldn’t even shake hands with men.

4. Orhan Pamuk encourages “gericilik” (backwardness). So does the government.

etc. etc.

The two sides deserve one another.

Lale

~Posted by Suat on 20/12/2005, 12:24:39

This is a trial staged by Orhan Pamuk to increase his reputation outside Turkey and to be portrayed as a free-speech activist. Turkish government and prosecution are just playing their roles as extras in this comedy-drama.

He is not hiding the fact that he knows that he could not be respected as an intellectual in Turkey unless prosecuted by authorities: “Living as I do in a country that honors its pashas, saints, and policemen at every opportunity but refuses to honor its writers until they have spent years in courts and in prisons, I cannot say I was surprised to be put on trial.” Even though he says he wasn’t seeking this honor, the article of the Swiss paper suggests otherwise because he blurted out those now-infamous words outside the context of the discussion and not related to any questions he was asked.

I am not against open discussions on any subject including the Armenian and Kurdish tragedies. There are many authors and intellectuals who paid (and some are still paying) heavy prize especially to discuss the latter topic. Have you ever heard of Ismail Besikci (http://www.etext.org/Politics/Arm.The.Spirit/Kurdistan/Articles/ismail-besikci.txt) who spent most of his adult life behind bars only because of his books and writings.

Orhan Pamuk started writing books in late 70s, and since then he had many novels published. Many of them are post-modern, and none of them were about Turkish politics or even Turkish life until Snow, which shows none other than his contempt of Turkish people. He was never political; he was never seen attending a political function, never uttered any word against the oppressions and aggressions happening in the south-east of the country. Now only after getting advise from his spin doctors, he decided to talk politics because that is the only way to win a Nobel prize for someone coming from a third world country.

Where was he during the last 25 years?

Suat.

Claire Berlinski

Pamuk: Prophet or Poseur?

The Globe and Mail, December, 2007

A review of Other Colors: Essays and a Story.

The novels of Orhan Pamuk, Turkey’s most celebrated and controversial man of letters, have been translated into some 20 languages. His novels Snow and My Name is Red are widely considered world-class achievements. The themes of Pamuk’s oeuvre include the conflict between the East and the West, the tension between Islam and modernity, and the intense melancholia of his native Istanbul. Admirers find his style complex, multilayered and allegorical; detractors find him faddish and incomprehensible.

On Sept. 11, 2001, writers treating the themes of East contra West and Islam contra modernity hit the literary jackpot. Pamuk — Eastern enough to write novels about Ottoman calligraphers and Islamic radicals, Western enough to write them in a postmodern, magic-realist style — became the darling of the Western literary establishment, serially winning the most prestigious and lucrative literary awards in the Western world: the IMPAC Dublin Award, the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade, the Prix Médicis étranger, the Premio Grinzane Cavour.

Then, in 2005, Pamuk remarked to a Swiss weekly newsmagazine that “thirty thousand Kurds, and a million Armenians were killed in these lands and nobody but me dares to talk about it.” By “these lands” he meant Turkey. By “nobody,” it is not quite clear what he meant; as far as I can tell — and I live in Turkey myself — nobody here will stop talking about it. But the sentiment in Turkey, generally speaking, is that the Armenians had it coming, and quite a few more Kurds want killing.

Pamuk seemed to be suggesting otherwise. The Turkish government brought criminal charges against him under the infamous Article 301, which forbids citizens from insulting Turkishness. Pamuk was in one stroke elevated from symbolist writer to symbol. The European Union’s Enlargement Commissioner called Pamuk’s case a “litmus test” of Turkey’s commitment to European values; writers around the world rightly denounced the charges as an outrage against free expression. In the end, the case was dropped on a technicality.

Facing death threats at home, Pamuk sensibly decamped for New York. But his prosecution, combined with his status as ambassador at large for the westernized Islamic world, functioned like camembert in a mousetrap to the Nobel committee, which in 2006 awarded him the Nobel Prize for literature. Pamuk is a talented writer, but no one in his right mind believes this was an award based on literary merit.

Pamuk has for the past three decades been filling his notebooks with sketches, half-finished short stories, thoughts about literature and reflections on the travails of life as a writer and a Turk. He has compiled them, loosely edited, into Other Colors, “a book made of ideas, images and fragments of life that have still not found the way into one of my novels.” Although it contains previously published works, such as his Nobel acceptance speech and the transcripts of various interviews he has granted over the years, it is mostly comprised of non-fiction essays written some years ago but only now seeing the light of day: literary criticism, reminiscences of his boyhood and particularly of his father, reflections on the challenges of quitting smoking, a discussion of his wristwatches, two short meditations on seagulls and their sad fates, ruminations on the pathos of being a Turk and the Turk’s endless, resentful fascination with Europe. There are more descriptions of Istanbul in the melancholy vein of his previous memoir, Istanbul: Memories and the City.

But this book is about Pamuk himself, particularly the challenges of being a great writer and a severe depressive. The collection has been received with rapture by many critics, who celebrate this offering as a unique window into Pamuk’s interior life. Indeed, it is precisely that. Unfortunately, it seems that Pamuk’s interior life is largely that of a lugubrious poseur.

“In order to be happy I must have my daily dose of literature,” Pamuk gravely introduces himself. “In this way I am no different from the patient who must take a spoon of medicine each day.” If you didn’t quite get the point, he repeats it again two sentences later: “For me, literature is medicine. Like the medicine that others take by spoon or injection, my daily dose of literature — my daily fix, if you will — must meet certain standards.” If he is forced “to go a long stretch without his paper-and-ink cure,” he feels “misery setting inside me like cement. My body has difficulty moving, my joints get stiff, my head turns to stone, my perspiration even seems to smell differently.”

Is he serious? Yes, he is. For page upon page, Pamuk stresses in these self-enamoured tones that he is a man who really likes to read books. Good ones, too, by famous writers like Dostoyevsky and Borges — not, you know, easy ones. He’s different from other Turks, you see. But he’s not like the Europeans, either. He’s an outsider, eternally apart, rejected by all, accepted by no one (the Nobel committee aside). Life hurts. A seagull croaks.

There is a fleeting moment of insight when he later remarks that he wants “to say a few things about my library, but I don’t wish to praise it in the manner of one who proclaims his love of books only to let you know how exceptional he is, and how much more cultured and refined than you.” He negates this half-hearted essay at modesty in the very next sentence: “Still, I live in a country that views the non-reader as the norm and the reader as somehow defective, so I cannot but respect the affectations, obsessions and pretensions of the tiny handful who read and build libraries amid the general tedium and boorishness.”

Sentiments such as these may make the reader suspect that Pamuk was prosecuted in Turkey not because he spoke the truth about Armenia and the Kurds but because he is a patronizing pest. But let’s not quibble: Pamuk needs to read or he will die. That, surely, is the mark of a particularly excellent reader. And he is, moreover, caught between East and West, which makes his affliction all the more acute.

Pamuk lived and wrote in Cihangir, a lovely neighbourhood on the European side of Istanbul. This happens to be where I now live and write. From Cihangir, if your window faces the Bosphorus, on a clear day you can see Asia. So I’m caught between East and West myself, not to mention caught between north and south, and caught, at least twice a day, between daytime and nighttime. (By the way, you would not know it from reading Pamuk, but it is usually a clear day here. Istanbul is a bright, vibrant, cheerful city.) It is physically impossible not to be caught between East and West, actually. We all are. So may I take this opportunity to beg Pamuk, everyone who writes about Pamuk, and indeed, everyone who writes about Istanbul, to retire forever the phrase “caught between East and West”?

Yes, Istanbul is located geographically between Asia and Europe. Yes, Turks tend to be rather aware of this. Turkey, as Pamuk observes– and if you think about it for even a second, it should not come as a surprise — exhibits both Oriental and Occidental qualities. But this “caught between East and West” business — how much more literary mileage does he plan to get out of it? First time: a fair observation. Thousandth time: 999 times too many. (Next up: New York is a melting pot; Paris is the City of Lights; there’s nothing in Texas but steers and queers.)

Even the hamburgers of his youth were, for Pamuk, “like so much else in Istanbul, a synthesis of East and West.” So were the frankfurters, in fact. And like everything in Istanbul, they made him feel gloomy. “I would look at myself standing there, eating my hamburger and drinking my ayran, and see that I was not handsome, and I would feel alone and guilty and lost in the city’s great crowds.”

For this is his ultimate subject: his very sad mood. Forget for a moment the literary accolades and imagine what it would be like to go on a date with this melancholy egomaniac. He shows up at the café wearing a black turtleneck, brandishing his annotated copy of Notes from Underground, making sure the title faces out. Within minutes he tells you that, unlike everyone else in Turkey, he reads. “Books are what keep me going,” he says.

“Really? I like books too,” you say politely.

“Let me explain what I feel on a day when I’ve not written well, am unable to lose myself in a book,” he adds gravely. “First, the world changes before my eyes; it becomes unbearable, abominable.”

“Oh,” you say. “That sounds very painful.”

“I feel as if there is no line between life and death,” he continues. “It’s worse than depression. I want to disappear. I don’t care if I live or die. Or if the world comes to an end, even. In fact, if it ended right this minute, so much the better.”

It is a bright spring day in Istanbul. He tells you that he hates the springtime.

Pamuk is a creature of Istanbul’s haute bourgeoisie, a class of Turks much given to examining their own misery and alienation and finding them intensely significant, much in the way the 19th-century romantics admired their own tuberculosis. The Turkish elite is, as Pamuk is painfully aware, a parvenu class.

What seems to escape him is that in stressing how much he reads and the quality of his taste, he does not display his distance from the social cohort from which he emerged. Rather, he marks himself as its caricature. Young women from this social class dye their hair purple and weep a lot. The older women complain of migraines. The young men are sent by their parents to psychiatrists who trained in the United States; they wear black trench coats, rarely shave and tell everyone who will listen that no one in Turkey understands them.

“Time passes,” Pamuk scribbles in his notebook. “There’s nothing. It’s already nighttime. Doom and defeat. … I am hopelessly miserable. … I could find nothing in these books that remotely resembled my mounting misery.” I suppose sentiments like these are not uniquely Turkish; teenagers around the world fill their diaries with this kind of drivel. But usually they read those diaries when they grow up, cringe, then throw them out along with their old Morrissey albums.

Mind you, Pamuk is not all gloom; he is immensely cheered by the thought of his own moral gravity: “A novelist might spend the whole day playing, but at the same time he carries the deepest conviction of being more serious than others.” He brightens up when he considers his own accomplishments, too: “Having published seven novels, I can safely say that, even if it takes some effort, I am reliably able to become the author who can write the books of my dreams.” Sometimes he works, he tells us, “with the incandescence of a mystic trying to leave his body.”

And did he mention that he really, really likes books? — although I do have to wonder, occasionally, just how carefully he is reading them; in his discussion of Nabokov, for example, he describes Humbert Humbert as a man who “searches for timeless beauty with all the innocence of a small child.” Beg pardon? Humbert searches for timeless beauty by molesting an innocent small child. There is quite a difference.

There are, here and there, flashes of the gloomy talent for which he is rightly admired. Reading the vignette A Seagull Lies Dying on the Shore, I felt quite bad for the seagull (although I am pleased to report that those same seagulls, which I see from my window, look perfectly healthy).

And there is one excellent section, quite chilling for those of us who live here, about the great earthquake of 1999. Pamuk recalls wondering whether, come the next big quake, the minarets of the Cihangir mosque would fall on his roof. I live next door to that very mosque. I had not thought of that. His comment prompted me to step outside and contemplate those minarets with a certain unease. Discussing the aftermath of the earthquake, Pamuk for a brief moment removes his gaze from the mirror and observes his surroundings with interest and even a hint of irony: “One rumour had it that the earthquake was the work of Kurdish separatist guerrillas, another that it was caused by Americans who were now coming to our aid with a huge military hospital ship. (‘How do you suppose they made it here so fast?’ the conspiracy theory went.)” Yes, there at last is an honest line; it will certainly sound familiar to anyone living in Turkey these days.

But the rest of the book is the kind of thing you can only publish if you have won a Nobel Prize and feel entirely confident that no matter what you say, everyone will buy it and the critics will be too afraid to point out the obvious: Sometimes it is best to keep your interior life to yourself.

~

Posted by Lale on 10/08/20016, 18:45:45

Earlier Solzhenitsyn was mentioned. It seems his warning was warranted:

http://rbth.com/arts/2014/05/20/solzhenitsyns_foresight_on_ukraine_proves_eerily_prescient_36791.html

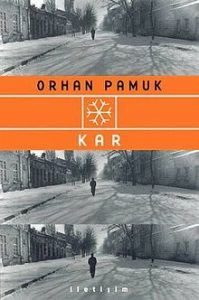

Snow – Orhan Pamuk – 2002