Saturday – Ian McEwan – 2005

Posted by Steven on 28/5/2006, 16:39:53

The full text of the poem that Daisy recites to Baxter:

Dover Beach

by Matthew Arnold

1867

The sea is calm to-night.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; -on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanch’d land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Aegean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furl’d.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

Posted by Lale on 31/5/2006, 10:05:53

Well, I have a strange ailment, if you can call it that. When I see/read/hear about a particular disease or a rather graphic description of its cure, it is as if I am suffering from that disease or as if that particular procedure is being applied to me. This was more dominant when I was a child and it seems to have eased up as I grew older and as I experienced more health problems myself. But last night, reading the first 10 pages of Saturday was hell. I felt as if they were doing brain surgeries on me, one after another, and without anesthesia. I hope Ian Mc Ewan doesn’t plan on going on with these descriptions.

Lale

~

Posted by Steven on 31/5/2006, 11:29:09

: Saturday : Well, I have a strange ailment, … it is as if I am

: suffering from that disease or as if that particular

: procedure is being applied to me.

Lale, you aren’t the only one. In college I took a course on parasitology. By the end of the semester I was a seething mass of parasites, suffering from every bizarre disease known to mankind – in my mind, at least. But now it doesn’t bother me in the least to read about such things. I still don’t like watching film of surgery, though.

: I hope Ian Mc Ewan doesn’t plan on going on with these descriptions.

Not all the way through, but… Just remember that it’s all metaphor (which will make Saturday a fun book to discuss).

Steven

~

Posted by the bunyip on 5/6/2006, 12:42:50

Did they teach you about Toxoplasma gondii in that course? It forces male crabs to believe they’re female and start stocking up on resources for egg-laying.

There’s a cousin of that parasite inhabiting the brains of an estimated 60% of the European population [and one supposes its emigrants]. Do you suppose knowledge of this might moderate North American gay bashing a bit?

Parasites driving behaviour change is the opening metaphor of Daniel C. Dennett’s “Breaking the Spell”. This book cannot be recommended enough. Especially since it addresses the greatest fiction of all – “faith” and religion.

the bunyip

~

Posted by Lale on 2/6/2006, 11:40:22

On the front cover of my copy of Saturday, it says:

“Dazzling. … A profound and urgent novel” – The Observer (UK)

What does an “urgent novel” mean?

I have heard all sorts of adjectives for descriptions of wine and classical music recordings (a round wine, an evasive third movement), and now it seems the trend is penetrating into book reviews.

What were some of the most ridiculous comments you have heard in praise of a book?

Lale

~

Posted by Pierre on 2/6/2006, 16:02:01

The comment I hate the most is the one I can hear the most ofen about french novels : when a stupid self-appointed so-called “literary critic” says of a book “…and also it’s very well written.” INDEED!

~

Posted by Steven on 2/6/2006, 20:46:20

: What does an “urgent novel” mean?

Maybe “urgent” is one step higher than “compelling.”

~

Posted by the bunyip on 5/6/2006, 12:36:52

McEwan’s book is urgent for a number of reasons, not least in the question of the justification for The Shrub’s ill-conceived Crusade in Iraq. Henry and Daisy’s discussion about the morality of “regime change” should have been aired before the invasion and by more people.

It’s “urgent” because McEwan presented a realistic world view in this book. He did it through an educated individual who resisted dogma, no matter how well intended. The end reflections on “Baxter” are something to read and consider very carefully. The implications of Henry’s stance have wide application.

Perhaps, it’s also urgent to understand how a man of Henry’s calibre went through life without knowing who Matthew Arnold was. I started to find that implausible, but perhaps not. The “humanities” haven’t shed their disdain of the scientific scholar’s mind. The point could have been belaboured in this book, but McEwan dealt with it gracefully. He cannot receive enough plaudits for his effort.

the bunyip

~

Posted by the bunyip on 5/6/2006, 12:27:39

G’day, Dear Lale and other Friends,

Having just closed the final page of this book, i’m anxious to entice and share views of it with others. It won’t all come at once, this book is worthy of much discussion.

Just for openers, any fiction writer who encorporates Darwin’s exquiste finale to “Origin” – “There is a grandeur in this view of life” deserves close attention and respect. I had come to believe such a device in a novel outside of [ug!] “SciFi” was still long in the future.

There’s also a bit of self-revelation due here – except for the qualified professional status, Henry is ME.

For those interested, Barnes & Noble University is holding a readers’ symposium on this book starting today. With a bit of luck we may entice some new participants to Read Literature. New friends are always valuable, wot?

the bunyip

~

Posted by Lale on 6/6/2006, 10:07:39

: today. With a bit of luck we may entice some new

: participants to Read Literaturee. New friends are

: always valuable, wot?

Yes, that would be great. Please do tell them about us.

Lale

~

Posted by Steven on 9/6/2006, 23:34:42

Saturday Wins James Tait Black Award

It was announced this week that Ian McEwan’s Saturday has won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Fiction. This is the UK’s oldest literary award and is presented by the University of Edinburgh Department of English Literature.

http://www.englit.ed.ac.uk/jtbinf.htm

http://www.awardannals.com/award/jtblack/novel/2005/

http://books.guardian.co.uk/news/articles/0,,1792232,00.html

Another award announced this week is the Orange Prize for Fiction, awarded for the best novel of the year written in English by a woman. The winner is Zadie Smith for On Beauty.

http://www.orangeprize.co.uk/

~

Posted by LadyPurple on 10/6/2006, 6:55:29

Thanks for posting this! And good news for McEwan and Saturday…

Being Saturday today I will be finishing it today – at least that is my intention and will post some thoughts tomorrow.

Those who can tear themselves away from the World Cup may join us…

Friederike

~

Posted by LadyPurple on 11/6/2006, 7:06:43

Finally, I finished Saturday… not that it was a struggle, just time distractions.

First off, I liked it a lot – I prefer it to Atonement which I thought was rather good but I had some issues with (touched on in my amazon review).

A Day in the Life of … Henry the Neurosurgeon fits McEwan’s style to a T. Intense is one word that comes to mind, an eye for detail in the description of place and people. The London he describes is very realistic, I can follow the walks, know the places… At the same time, he is somewhat distant in his reflections on life and events – except, maybe, for his feelings for his family, and above all, Rosalind.

The research that McEwan undertook to get the neuroscience right in a way that it seems absolutely in character must have been amazing. One wonders what prompted him to do that. Cases in his surroundings? Why else? His description of his mother deterioration made me uneasy as it reflected so closely what I am going through with mine.

The reflections on the discussions with Daisy and literature were interesting and, again, very much in character. His appreciation for his son’s music was more surprising.

The demonstration and the run up to the Iraq invasion was less prominent, I thought, than I expected from the reviews and discussions on the book. The burning plane took more of Henry’s mental space than the demo.

Baxter – another discussion point.

I am rambling along here – somebody else should so that we can have a discussion

Friederike

~

Posted by Steven on 11/6/2006, 10:09:04

Saturday was a very interesting novel with much food for thought. It makes an good parallel between how we recognize and deal with evil as individuals versus as a society. Another issue is the risk of incorrect first impressions at a time of high emotion.

I have one negative thing to say about the book, and I’ll get that out of the way first:

Henry Perowne is just too perfect to be convincing. He is a brilliant neurosurgeon, a versatile athlete (squash and marathon), a loving husband, a dutiful son, a benevolent and understanding father, a talented singer and musician and a great cook. He is fair, compassionate, heroic, humble, loving and decisive. His only “weakness” is his lack of appreciation for literature – a small window of opportunity for author and reader to retain a sense of self-worth in comparison to this paragon. But if such a near-perfect human being thinks invading Iraq is the humane thing to do, who are we to argue?

I did, none the less, appreciate the detailed and convincing treatment of Henry’s activities – from surgery to squash to blues to fish stew.

And there is much more in this book to talk about, but I have to go trim some shrubs before it gets too hot to set foot outside…

Steven

Posted by Lale on 11/6/2006, 10:43:08

: I have one negative thing to say about the book, and I’ll get that out of the way first:

: Henry Perowne is just too perfect to be convincing. He is a brilliant neurosurgeon, a versatile athlete

: (squash and marathon), a loving husband, a dutiful son, a benevolent and understanding father, a talented

: singer and musician and a great cook. He is fair, compassionate, heroic, humble, loving and decisive.

I am very relieved to see that you opened the door here Steven. Because I will enter through that door and take a few steps:

All Ian McEwan’s characters are near-perfect. In this book, the four main characters (even the fifth, the granddad) are all well-accomplished, successful, brilliant people; they can do no wrong. Theo, a high-school drop-out, jams with world’s most famous musicians and doesn’t have an attitude towards his parents, doesn’t drink alcohol, doesn’t smoke … Both children are perfectly loving, home kids. When Daisy finds her soul-mate, he too comes from a rich family and the newlyweds abode is immediately provided for.

Previously, I read Amsterdam, Black Dogs and Enduring Love. Characters are always from a highly elite uppercrust. They are composers, newspaper editors, writers, poets, artists, cabinet ministers, lawyers, neurosurgeons… They drink the best wine, listen to fine music, cook gourmet food. They never have any money problems. If one side-character (such as Grammaticus, the granddad) has a weakness or a slight obsession, it is still all very well since this character is fabulously rich to compensate for it.

At every page something from high-society is described in detail: an antique coffee table, a Persian rug, a mercedes…

Henry Perowne sure knows how to drop the names of a lot of books/authors for someone who doesn’t read. He knows the subtleties between a Glenn Gould recording and an Angela Hewitt recording of the Goldberg variations.

It was tiresome, this continuous awe for the rich and the successful. Or maybe I have read too much Balzac to re-adapt to the “real world”.

Lale

~

Posted by LadyPurple on 11/6/2006, 11:48:20

We see the other characters mainly through Henry’s eyes. We don’t know much about them independently. Daisy is back, pregnant and her father didn’t know or guess… By the way, Giulio is a boyfriend not a husband – whether he ever will is a question mark as we only know, via Rosalind, that Daisy is madly in love…

I have only read Atonement and there you have the very stark social tension between the upper middle class family and the local boy from a labourer’s background. The tensions go through the book. In a way, as here with Henry and Baxter. By the way, the Perownes are well-off middle class – not really the rich set – wrong neighbourhood and wrong passtimes. Rosalind wouldn’t work her butt of as she obviously does, they would not have started out in a one-bedroom flat in Archway I can assure you. I lived around there. Anyway, I am probably not the best judge as for me so many aspects of the book are familiar to my own experiences.

more to come I hope – who are you betting on to win the game?

Friederike

~

Posted by LadyPurple on 11/6/2006, 11:35:56

Thanks for getting us going here, Steven.

Henry’s “near perfectness” did not really bother me that much – I know people like that in London (and elsewhere) – I would add that, despite this, Henry asks himself a lot of questions – regarding his performance – as a husband, father, squash player, son… regarding his wealth, which is not really his, etc. As he reflects on his life and place, he has doubts about a lot of things, debates with himself and wavers in almost everything except for his decisions in the operating theatre and at the end of the book. His position on the impending invasion of Iraq is also not clear cut. In his discussion with Daisy, McEwan is careful to note that both do not belong into the stereotype label of pro and con the war, that the media gave everybody at the time and – to a degree – still is.

As you say, there is a lot more to talk about in this book. I read about the comparisons to Mrs. Dalloway – did you read this Virginia Woolfe novel? Istarted it when I read The Hours but never really got into it. So I cannot comment. On the other hand, I would think that McEwan does not need a model for his novels to help him structure a story…

Friederike

Posted by the bunyip on 13/6/2006, 9:41:13

G’day, All,

As I’m in other discussion groups about this book, I’ve encountered this “too perfect” judgement elsewhere.

I can’t voice my dissent strongly enough. Not having read other McEwan’s my neurons aren’t tainted by his feelings about “the rich and the powerful”. There are good, skilled, comfortable, inquisitive, caring people out there. Why not write a book about one of them. Despicable as our species is, “Bleak House” doesn’t have to set our standards for reading.

The complaints about Henry verify why I don’t read much “litrachure”. The mythologies recylced through most fiction, which demand we sit in judgement of the characters, and hence, the rest of humanity, is a false foundation. McEwan has taken a first small [very!] step in correcting this chain that binds us. McEwan shows there is [as there must be] a place for the rational and reasonable. Calling Henry “perfect” is a misdirection. He has very human feelings, fears, hopes, experiences. That he happens to be mentally one step up from the Great Unwashed should not cause us to condemn him, nor McEwan from portraying him.

The main thing is that McEwan conjured Henry up precisely and flawlessly. Except for my lack of neurosurgical skills, there stands the bunyip in all his tarnished splendour. McEwan got it in one!

ta,

the bunyip

stephen

~

Posted by Ladypurple on 16/6/2006, 17:45:45

Hi Steven,

I wanted to go back to your message – I am wondering – we got stuck in arguing the negatives rather than the interesting aspects and the food for thought you mention. It would be good to hear more about that – thanks

Friederike

~

Posted by Lale on 12/6/2006, 10:19:10

More comments:

I liked the book but I didn’t think it was “great”. It is certainly forgettable, as far as I’m concerned.

The inordinate amount of detail bothered me. To extend the time between two plot elements, McEwan goes into excruciating detail:

“… he hears the solid clunk of her wardrobe door opening, the vast built-in wardrobe, one of a pair, with automatic lights and intricate interior of lacquered veneer and deep, scented recesses; later still, as she crosses and re-crosses the bedroom in her bare feet, the silky whisper of her petticoat, surely the black one with the raised tulip pattern he bought in Milan; …”

It is not only the extent of detail that irked me but also its pretentiousness. I know people who talk, in the style of McEwan, about their vast built-in wardrobes and their silk petticoats, purchased in Milan, with raised tulips; I find these people very boresome. Owning lovely things is OK. Describing them to friends is OK. It is just the insincerity of the style that bugs me.

Back to the quantity of detail:

The blue shorts are bleached by patches of sweat that won’t wash out. Over a grey T-shirt he puts on an old cashmere jumper with moth-holes across the chest. Over the shorts, a track-suit bottom, fastened with chandler’s cord at the waist. The white socks of prickly stretch towelling with yellow and pink bands at the top have something of the nursery about them. Unboxing them releases a homely aroma of the laundry.

Then, he moves on to the squash shoes. Please, be honest, do you really think a pair of socks deserve 31 words?

Do we really need the specifics of Henry Perowne’s urination (sitting vs standing)? Maybe, Ian McEwan worried that some of his readers would assume, unless explicitly spelled out, his character didn’t suffer from banal bodily functions of the mortal since he is made to be such a superhero. No, no, he needs to pee, just like every one else. Good to know. But couldn’t we at least do without “He rises and flushes his waste.”? And that, at the opening of a new paragraph! I think Ian McEwan is underestimating his readers. We couldn’t have imagined Henry Perowne not flushing his waste and risking it found by his lovely wife in her black silk Milanese petticoat with raised tulips.

I read Mrs. Dalloway which is not about plot but about inner thought. I also read Malcolm Lowry’s “Under the Volcano” which takes place in 12 hours. These books didn’t try to extend the story by minute and unnecessary detail.

With Saturday, as with all other Ian McEwan books I have read, I had the feeling that it would make a much better short story than a “novel”.

Lale

~

Posted by Lale on 12/6/2006, 11:03:38

Stephen the Bunyip: I am looking forward to more of your comments. Please forgive me for bad-mouthing this book. I know I am hung up on some stylistic issues, but they made the reading experience unpleasant for me, so I couldn’t hold them in.

Here is Stephen’s review from amazon (I only object to “action packed”, I didn’t think “action” was “packed”, I rather found the “action” dispersed; getting to the action was like playing scavenger hunt):

Action-packed! Romantic! Gripping! . . . and introspective? , June 9, 2006

Reviewer: Stephen A. Haines (Ottawa, Ontario Canada) – See all my reviews

(TOP 100 REVIEWER) (REAL NAME)

Taking us through one day of Henry Perowne’s life must, in less than 300 pages, necessarily result in an “action packed” story. Opening with Henry’s discovery of a fiery jet crossing the sky in the early hours, we follow his busy day of surgery, auto smash, family relations and musings on his life. McEwan’s story is intense. It could be no other way, given the complexity of Henry’s life. The author, however, keeps tight control over the narrative relieving the reader of “interpreting” events. This is far from “escapist” fiction, and the reader is kept attentive to meanings and values. McEwan contrives nothing and the reader will have few questions or worries about plausibility. A brilliant work about real people.

A serious professional, Henry’s “relaxation” is an intense squash game with his anesthetist. He’s approaching the big “five-oh”, time when any reflective man will look back on his achievements and disappointments. Henry seems to have few of the latter. His daughter is a poet about to be published. Naturally, with her living in Paris, he worries about her private life. Laced with erotica, her poetry seems to impart much. Perhaps more than Henry wants to hear. Having a daughter is an effective way to age a man. Daisy’s intelligent and deeply committed. On this Saturday, she’s committed to blocking the Bush-Blair crusade in Iraq. A great march will take place, and Daisy expects her father to participate. His demurral shocks her and McEwan provides a charged confrontation – the “generation gap” is still with us.

Whatever Henry might have wished about attending the march is circumvented by a light road accident. A car brushes his, and he faces a trio of London street toughs. Their leader, “Baxter”, is a complex character. His opening line to Henry is priceless. The author effectively summarises the thug’s character in a single sentence. Obviously educated, Baxter suffers from a genetic neurological disease, Huntington’s chorea. Spotting this immediately, Henry diagnoses the ailment, offering therapy. The exchange leads to a string of multi-level encounters between Henry and Baxter. Henry’s values are challenged in many ways by Baxter, whose own values must shift as they interact. The balance is exquisite as Henry and Baxter strive to maneuver each other through a spectrum of the two men’s shifting needs. McEwan maintains this equilibrium with adroit finesse. In the hands of a lesser writer, it would be merely a clash of wills or a formulaic “good versus evil” scenario. McEwan effectively avoids such simplistic insults to the reader, and we can only applaud him for his skills.

Although shunted to justifiably minor roles, the remainder of Henry’s family orbit about him, plainly visible. Each shines with their own level of brilliance. Henry’s father in law, John Grammaticus, is a poet, thus Daisy’s mentor. Theo, a teen-aged son, is caught up in blues music. In most fiction this would lead to friction, given the contrasting worlds, but father and son evince only mutual respect. Henry’s mother, suffers advanced dementia, residing in a home. The great luminary in Henry’s family is his wife Rosalind. A lawyer, she has her own professional realm. Henry loves her ardently. In yet another break with formula, Henry is given no amorous distractions neither among his hospital colleagues nor elsewhere. All the romance centres on Rosalind, with neither erosion nor regret. It’s to McEwan’s credit that he avoids this stereotype trap.

Rather unexpectedly for fiction, Charles Darwin’s famous aphorism, “There is a grandeur to this view of life” appears. It’s a key statement in this story. Henry’s view of life is grand, and based on solid reasoning. His scientific background forces that approach, and leaves more emotional responses to issues beyond his ken. Daisy never comprehends why Henry won’t protest the crusade, but his knowledge exceeds hers and his values run deeper. Should he explain his position in better detail? Would she have accepted his argument? Growing up is hard to do, but watching it happen can be worse. Henry’s “view of life” reaches beyond Daisy’s, reinforcing the distress by her incomprehension.

With the many aspects of life this book offers, presented with vivid clarity and stirring insights, McEwan may well have launched a new “wave” in fiction. The reality underlying the story and its characters may provide an example for others to follow. They will, however, have to learn to work. McEwan spent two years learning what a neurosurgeon does. How many novelists will undertake, or endure, such an apprenticeship? This could have been a work of journalism. Instead, it’s a brilliant story for all to enjoy. [stephen a. haines – Ottawa, Canada]

Posted by the bunyip on 13/6/2006, 9:46:36

G’day, Lale,

: Here is Stephen’s review from amazon (I only object to

: “action packed”, I didn’t think “action” was “packed”,

It’s clear we need to get you to a chemist’s and obtain some “laughter” pills. I was being ironic with that title. That many events of such intensity in one day certainly seems “action-packed” to me.

Besides, I had to get away from the gazillion other mostly flat listings for it . . .

ta,

the bunyip

@

Posted by Lale on 13/6/2006, 10:14:11

: That many events of such intensity in one day certainly seems

: “action-packed” to me.

That is true, my dear Stephen, a lot did happen in one day.

Most of what happened (squash game, visiting the mother, attending Theo’s rehearsal) were already planned for that day. I thought, if you have a brush with death (or at least the possibility of a good trashing by a street gang), you would cancel some of your activities for the day. I found it unrealistic that he goes on with the squash game and then goes and visits the mother. She is in the same town, he could have easily left that for the following week. Ian McEwan trying a little too hard to make the day really “full”, I don’t mean just busy, but full with different aspects.

Lale

~

Posted by the bunyip on 14/6/2006, 6:53:11

It seems to me we can cut McEwan a bit of slack on time compression. It’s just a literary device. After all, if you’re going to write fiction, gimmicks are a dime a dozen. It’s only the truly implausible that are objectionable.

The real issue is how Henry deals with the succession of events. McEwan is depicting somebody who considers life, or at least his own, something to be kept in check. He may not “control” life, as some have argued, but Henry’s ability to cope is strong.

We could spend much time discussing how Henry achieved that, but i don’t know how fruitful that would be. For openers, I don’t know his family heritage, which would be a helpful foundation.

ta

the bunyip

~

Posted by Steven on 12/6/2006, 12:27:06

: Lale wrote:

: It is not only the extent of detail that irked me but

: also its pretentiousness.

I wasn’t especially bothered by the amount of detail – except when the squash match dragged on forever. Do you think the intent may have been to make the novel more realistic by giving it a pace and tone that matched real life rather than fast-forwarding between the good parts?

I found the pretentiousness more annoying, especially when coupled with Henry’s pristine character. At the end I was rooting for Baxter to take “Dr. Perfect” down a peg. Is there any chance McEwan expected a reader to react that way? Probably not, from what you say about his other books.

How much do you think McEwan was trying to create a direct parallel between Henry/Baxter conflict and that of the US+UK versus Iraq?

Steven

~

Posted by Lale on 12/6/2006, 13:59:36

: except when the squash match dragged on forever.

Oh God, yes, it did go on for ever. Now I know what is more boring than watching a squash game: Reading about it.

Lale

~

Posted by LadyPurple on 13/6/2006, 10:03:01

I agree that it went on for a bit too long and detailed. However, to paint a consistent picture of Henry, this level of detail was ‘de rigueur’ I think. We don’t have to like the character to accept that he is well drawn. I remember our discussion on The Conservationist – not a pleasant character but he was well drawn and consistent as such.

FK

~

Posted by LadyPurple on 13/6/2006, 9:59:14

I wanted to comment on your point re parallels…

: How much do you think McEwan was trying to create a

: direct parallel between Henry/Baxter conflict and that

: of the US+UK versus Iraq?

I would have never thought about that and I would doubt that McEwan had this in mind. For Henry Baxter was a potential patient and once he had diagnosed his condition, he could not see him in any other light which, potentially could have been deadly for him (Henry). To me the brewing Iraq conflict was more an ominous backdrop, an impending threat to the peace and quiet and positive emotions that Henry was feeling on that day – to his own surprise.

Friederike

~

Posted by the bunyip on 14/6/2006, 7:01:23

> “How much do you think McEwan was trying to create a direct parallel between Henry/Baxter conflict and that of the US+UK versus Iraq?”

Not in any manner whatsoever. After reading this I struggled manfully to find a parallel and there isn’t one. What do you see that leads you to that conclusion?

There’s a far closer parallel in McEwan’s reference to Henry reading [Janet Browne’s??] “new” biography of Charles Darwin. In the 1990’s we all endured “the Darwin Wars” in which Yank Stephen Jay Gould attempted to erode the image of Darwin with his idea of “evolution by jerks”. Gould was roundly refuted by Richard Dawkins leading to a TransAtlantic essay war.

The “Jay” character seems rather more subtle and farfetched an equivalent than i hope McEwan would stretch to, but you never know . . .

the bunyip

~

Posted by Steven on 14/6/2006, 10:33:12

: > “How much do you think McEwan was trying to

: create a direct parallel between Henry/Baxter conflict

: and that of the US+UK versus Iraq?”

:

: Not in any manner whatsoever. After reading this I

: struggled manfully to find a parallel and there isn’t

: one. What do you see that leads you to that conclusion?

Simply that the way Henry handles Baxter is a lesson in dealing with violent threats that could be applied to a conflict at any level.

Posted by Bunyip on 20/6/2006, 8:33:30

G’day, Steven,

> “Simply that the way Henry handles Baxter is a lesson in dealing with violent threats that could be applied to a conflict at any level.”

Right. If you say so. For myself, I think this is a bit of an overgeneralisation. In itself, squash isn’t a “violent” threat. It’s play is vigourous and there’s no end of stress in dealing with conditions. But there’s no hint of personal violence. In fact, these two wouldn’t be playing over such a long period if that entered the picture.

The real threat to Henry in the game isn’t Jay, it’s the calendar. If Henry fails to succeed, it’s a sign the calendar is winning and he must adjust to a change in status. He must constantly be on the lookout for signs of that erosion in all aspects of his life.

In itself, “violence” is a disruption in these challenges which Henry is able to address and contend with on a scheduled basis. That’s why Baxter’s entry in his life is so important – it’s wholly unexpected.

the bunyip

stephen

~

Posted by Steven on 21/6/2006, 16:12:14

: Right. If you say so. For myself, i think this is a

: bit of an overgeneralisation. In itself, squash isn’t

: a “violent” threat.

Stephen, I think there’s a missed point here. I wasn’t talking about squash game with Jay at all. I was speaking of how Henry responded to Baxter.

At their first encounter, Baxter uses violence and threatens more. Instead of responding with violence, Henry measures the risks and responds with intelligence and compassion. This defuses the situation.

That night at Henry’s house, Baxter crosses the line and threatens Henry’s family. Henry responds with violence, but just enough to secure his loved ones. His first priority is to protect his family, after that it is to treat Baxter, not to take revenge.

Apply this approach to international affairs, such as Iraq and you have the following credo: Respond to irrational violence with understanding, not retaliation. When the threat becomes intolerable, use violence, but only enough to remove the threat to our citizens, then aid in the other nation’s recovery in the hope of making them a friend.

Given the backdrop of the war protests, I think McEwan would expect and intend that we should draw this parallel.

Steven

~

Posted by the bunyip on 23/6/2006, 8:53:18

G’day, Steven,

One of the reasons I avoid fiction is the tendency for its readers to impart meaning. Since there are more meanings available than stories, it’s easy to end up in an arena weilding weapons made of vapour. I think your ideas are terrific, but I don’t think they apply to this novel.

I think it’s wholly artificial to equate personal relationships between two people with international affairs. The foundations for action are almost wholly different.

Henry’s relation with Baxter doesn’t compute to “Coalition” and Iraq. Henry’s task is personal survival, tinged with a professional pride in making a “street diagnosis”.

An aspect of this relationship is Henry’s total avoidance of “typing” Baxter in any manner. He doesn’t view him as a larrikin, confidence trickster [could the collision have been purposely initiated?] or even impart racial overtones [in another discussion board, somebody assumed Baxter was black because he was aggressive]. This is unusual both in a character and a writer. The “us and them” issue never occurs. In international relations, it’s fundamental.

In my view, McEwan’s trying to tell us that we carry around many preconceived notions about our fellow humans. Very few of these are based on a foundation of knowledge about our species. Henry’s dismissal of fiction, especially “magical realism”, is indicative. Novelists have been recycling long-standing myths for a long time. Breaking that spell will require a great deal of work. McEwan has offered the first nudge.

the bunyip

~

Posted by Lale on 12/6/2006, 14:11:52

: The research that McEwan undertook to get the

: neuroscience right in a way that it seems absolutely

: in character must have been amazing.

Definitely tremendous research. In the acknowledgements he says that he had watched one surgeon “at work in the theatre over a period of two years”.

The details of Baxter’s operation were very tough to read for me, because of the mental problem I mentioned earlier. However, the absolute worst was the descriptions of the Huntington’s disease. While reading, I was displaying some of Baxter’s symptoms. It was awful.

Huntington’s is really a terrible disease, worse than Alzheimers, I came to conclude after reading this book. Because Alzheimers at least allows a long period of fulfilled life. Whereas Huntington’s can hit at a young age. Parkinson’s can also hit at an early age but Huntington’s, has a much wider spectrum of disturbing (for the patient and the society) effects.

Lale

~

Posted by the bunyip on 14/6/2006, 9:20:25

It’s been interesting watching the commentary on this book from various sources. Henry’s “perfection” and dealing with “threats” is one theme. There are others.

What is lacking is a closer look at two significant figures. Rosalind, supposedly a powerhouse solicitor in the office, seems pretty subdued at home [having a knife at her throat notwithstanding]. She seems to play a dual role in life, and i can’t help but wonder if McEwan is depicting her in her “natural” and “artificial” roles. There are valid grounds for this, but nobody seems to have twigged to them.

A good one-liner, particularly if it depicts a character has always appealed to me. One of my favourites is John LeCarre’s description of Hilda, to whom Anne Smiley would go for refuge: “Hilda was a divorced woman of some speed”.

McEwan introduces Baxter with his opening line about “I expect you’re sorry . . . “. To me, this statement transforms a street larrikin into a youth with education and feelings, trapped in a social milieu he can’t escape. The later acknowledgement of his Huntington’s and his obvious quest for therapy indicates he’s no clot, but no less trapped for that. He abandons his threat to the family at the first whiff of positive information about his condition.

Baxter would make a superb subject for a tragic novel. Wish I could write it.

the bunyip

~

Posted by Ladypurple on 16/6/2006, 17:47:46

I think Baxter deserves some additional reflection. Who is he and what does he represents in relation to Henry and, by extension, the rest of the family…

Friederike

~

Posted by Lale on 17/6/2006, 11:06:45

: I think Baxter deserves some additional reflection. Who

: is he and what does he represents in relation to Henry

: and, by extension, the rest of the family…

It was impossible not to pity Baxter, but he was also member of a street gang who did bad things. After the accident, Baxter punched Henry, nice and strong, without any preliminaries. Then, he proceeded to order a beating. Now, how Henry managed to got out of a bloody trashing (death was also a possibility) was something only Henry could do, any other person (a normal person, a less perfect person 🙂 )would have been in serious trouble. And that is not forgiveable. Your doom doesn’t give you a right to beat up or kill other people. And remember, this was all before Henry “humiliated” him instead of his peers. So it was uncalled for. Even if we accept the evening trespassing, holding people at knife-point and abasing Daisy were all acts that were provoked by the earlier encounter, we still cannot find any excuse for the first agression.

I understand the mood swings that come with the disease but I suspect other sufferers take to the streets and act like bikers’ gangs.

What I am trying to say is that Baxter had chosen the wrong path, no doubt influenced by his horrible predicament, but he was in the wrong nonetheless. He was the bad guy. We pity him but he is about to do horrible things to innocent people. Therefore, I did not share Henry’s afterthoughts on misusing his professional knowledge. Yet again, any other person would have been patting himself on the back for a smart escape, but of course our Henry would doubt his actions and ponder about ethics.

I think Henry was right to worry about having provoked Baxter and he was right to worry about a retribution, but he was a little artificial in worrying about the moral code. He didn’t do anything wrong. He just saved himself from a possible bloody death. Henry’s self-questioning that looked almost like if he was wondering he broke the Hippocratic Oath was just typical of all the things Henry does and says that make me dislike him.

Feelings of sadness and pity for Baxter are real. We felt them and Henry felt them. Also, Henry’s anger is perfectly acceptable: After providing the first aid and doing what a doctor can do for someone who is hurt, he thinks that he was so angry with this man that he didn’t even want to help him. That is human. It is normal to feel such anger towards a man who terrorizes your family and who threatens to kill your wife. Henry stabilizes the hurt man and provides first help and afterwards realizes that there was a moment when he didn’t want to do it.

Lale

~

Huntington’s: New Developments – Posted by Lale on 18/6/2006, 9:18:01

This is from yesterday’s Globe and Mail:

Huntington’s findings called ‘crucial step’

Posted by LadyPurple on 19/6/2006, 6:15:51

Thanks for posting the article. I saw it in the Globe as well. Interesting development from the discussion of Henry and Baxter…

Friederike

~

Posted by Ladypurple on 21/6/2006, 15:13:12

Hi all,

Do I take it that no more wisdom is to be exchanged regarding Henry, Baxter and other players in the day that was the brainman’s Saturday?

Any final thoughts? How many stars (hearts) for the book by those who have read it? I am between four and five. Still have to write a review…

Friederike

~

Posted by Lale on 21/6/2006, 15:25:10

: Do I take it that no more wisdom is to be exchanged

: regarding Henry, Baxter and other players in the day

: that was the brainman’s Saturday?

For people who liked Saturday, I highly recommend Amsterdam. In my opinion, it is Ian McEwan’s most original work.

: Any final thoughts? How many stars (hearts) for the

: book by those who have read it? I am between four and

: five. Still have to write a review…

I will give it three stars, can’t do more. I didn’t think it had enough substance to tie me to the book.

Lale

~

Posted by Steven on 22/6/2006, 9:36:07

I’ll go with three and a half stars. On the positive side, I found the book enjoyable, mostly interesting, and occasionally suspenseful. The neurosurgeon’s perspective on human behaviour was convincingly depicted. It was also worthwhile just to see how Henry reacted to and dealt with a wide range of crises and challenges during the day.

On the negative side, some episodes were overlong, and Henry and his family were too perfect to be convincing or evoke much sympathy. I felt no empathy for Henry’s concerns about his aging body or any of his family problems – it’s hard enough just to avoid feeling petty resentment that there should be someone so well off in the first place.

The half star is for McEwan’s setting the novel against the impending war in Iraq. This documents, in a literary sense, the way such events colour people’s lives even while we go on with our daily routines and manage our personal crises. His description of people and places overall was very strong, making it easy to visualize the characters and setting.

Though I don’t rank Saturday among my favourite books, I wouldn’t hesitate to read more of McEwan’s work.

Steven

~

Posted by Lale on 22/6/2006, 11:15:27

: and occasionally suspenseful.

Yes, I found it suspenseful too, and I liked that aspect of the book, but I also thought the suspense (and the curiosity) wasn’t sustained because there was too much description, unremarkable goings on Henry’s thoughts in between suspenseful happenings, and during them as well.

: The neurosurgeon’s

: perspective on human behaviour was convincingly depicted.

I agree. The part I liked the best was the representation of two parties after an accident. who will make the first move, who will gain the upperhand… Baxter offers cigarettes and that puts him in a better position than Henry. So, Henry gives his hand and says “Henry Perowne”.

The reluctance of Henry to get out of the car after the accident was probably what everyone feels in the same situation. It is done, it is over, your car is ruined forever (something has been taken from it, it will never be the same again) and you can’t believe it, you sit there thinking that maybe the time will go back a minute.

: Though I don’t rank Saturday among my favourite books,

: I wouldn’t hesitate to read more of McEwan’s work.

Start with “Amsterdam”. Suat highly recommends “A Child in Time”.

“Black Dogs” is pretty much like “Saturday”. Also set against the backdrop of a historic event (the fall of the Berlin Wall) and also consisting of perfect people with perfect lives. The only thing that is wrong with one of the characters is that she has 6 toes on each foot. (She has them surgically removed of course).

The other book I read was “Enduring Love”, very interesting topic but done overlong à la McEwan. The “very interesting topic” is some sort of an obsession/amorous delusion or les psychoses passionelles. The topic really interested me but I couldn’t bear with the repetitive and overdrawn style of the book. At the end of the book there was a “case study”. I thought this was a real mdeical case study. It summarized the entire book. I told my husband to just to read the 4-page case study instead of reading the whole book, he did, and afterwards we both knew as much about what had happened in the book. Later on I was told that this appendix (case study) was also fiction, written by McEwan himself (the psychological disorder is real, however).

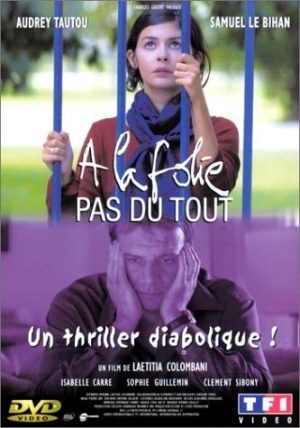

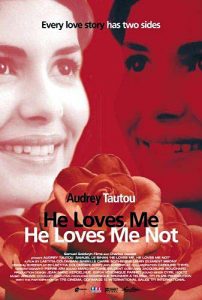

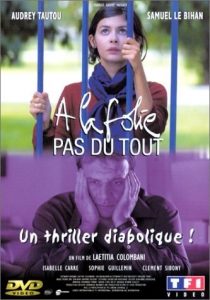

If the topic of Enduring Love interests any one here, I highly recommend a very smartly done Audrey Tautou movie on the same topic:

À la folie… pas du tout (2002)

… He Loves Me… He Loves Me Not (International: English title)