Life: A User’s Manual – Georges Perec – 1978

#OULIPO #DavidBellos

The following is a compilation of discussions and reviews from the previous version of our website. We hope you enjoy these older deliberations. Just beware, there may be spoilers in here. To add your own review or remarks, please scroll down to the comment box. — ReadLit Team

Posted by Christopher on 23/7/2004, 10:49:33

“Quelle est la menthe qui est devenue tilleul? qui surmonte le chiffre 6 dessine artistiquement.”

Nice puzzle on p. 29. How is it translated in English?

The answer:

la menthe = amante

le chiffre 6 dessine artistiquement = beau 6 = Baucis

After their wishes Baucis and Philomene were wrapped eternally in a linden tree = tilleul.

No, I didn’t find the answer on my own!!! But, this book is a lot of fun,

~

Posted by Lale on 24/7/2004, 9:01:3

Qui boit en mangeant sa soupe

Quand il est mort il n’y voit goutte

Here is my attempt:

He who drinks while eating supper

Will not see anyone cry for him when he is dead

???

Or

Will not see a drop of alcohol when he is dead because he will go to hell ?

~

Posted by Pierre Pigot on 24/7/2004, 9:53:26

“N’y voir goutte” = to be blind, to see nothing.

I never heard this proverb.

~

Posted by Lale on 24/7/2004, 10:21:31

: “N’y voir goutte” = to be blind, to see nothing.

Hmmm. It doesn’t make a lot of sense. Anyone who is dead will be blind, sort of. Interesting. Maybe there is another puzzle in there.

By the way, in the English rendition (translated by David Bellos) “Qui boit en mangeant sa soupe/Quand il est mort il n’y voit goutte” is provided thus:

He that with his soup will drink

When he is dead shall see no wink

~

Posted by len. on 23/7/2004, 8:37:41

“Gerturde of Wyoming” reference can be found at:

VOICES FROM 19TH-CENTURY AMERICA

Because some texts are just too interesting to leave in the library

The site says:

“Gertrude of Wyoming,” by Thomas Campbell (1809)

While Campbell was a British poet, this work on an incident during the American Revolution was popular with early 19th-century American readers and can be difficult to find. A version published in the U. S. in 1865 is transcribed here: http://www.merrycoz.org/voices/GERTRUDE.xhtml

~

Posted by Lale on 23/7/2004, 9:23:26

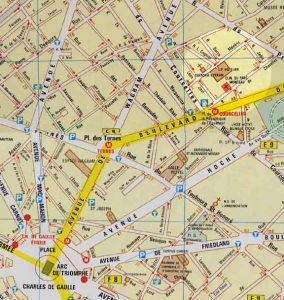

Rue Simon-Crubellier

To provide some context, I assembled this quickly from two different map pages that were of slightly different scales; hence there is some misalignment if you look too closely. But the highlighted area where the fictional street (Rue Simon-Crubellier) that the apartment building is located on is unaffected.

Posted by Lale on 28/7/2004, 8:53:40

This is one of the most popular of Turkish puzzle rings. It has four rings and it is one of the most difficult to make.

Before leaving for Trafalgar…

Posted by Pierre on 28/7/2004, 14:43:35

Dear booklovers from all over the world.

Next friday, I’ll leave rainy-windy France for the ever-sunny Spain of my mother’s mysterious ancestors. Of course I take a book with me : it’s always a cruel choice, because the book must be not too fat, but not too small, not too difficult but still interesting, and so on. Two years ago, it was “Anna Karenin” (wonderful, absolutely wonderful – a thousand stars writer, this Léon!). This year, it’s “Don Quixote”, which I’m going to read directly in Spanish. I bought it on the boulevard Saint-Michel at Gibert Jeune (I thought of you, Lale).

Hum.. Why was I saying that? Oh yes!

The consequence is that I won’t have the time to achieve my reading of Perec. I’m very happy to see that many of you love the book, and even try (avec une admirable persévérance) to read it in French – thus making disappear all my fears (“the book is too long”, “they probably don’t like this sort of story”, etc.) I chose it because I wanted to make you discover a new side of French literature, more recent, and maybe more complex than the sort you were used to.

Nevertheless, before vanishing, I have some questions to debate with for you :

– the descriptions : did you find them rich and with a marvelous precision, or did you find them a bit tiresome and monotonous? I have mixed feelings on this subject : I think that on the beginning it is a refreshing change, but through the reading it is sometimes a bit repetitive.

– the catalogues : Perec was fond of catalogues, neverending lists of things. Did you skipped them? (I confess I skipped the tools catalogue at the beginning of the novel).

– the stories : I loved them all! When I read one of the first (about the Holy Grail vase), I enjoyed it greatly, and I thought : “Well. Now, I don’t need to read the Da Vinci Code” [which is also a besteller in France, by the way…] – and every story following these one were enchanting in their rythm, variety, and even subtle humor.

– the “mainstream” story of Bartlebooth and his Great Project : I think it is the very structure of the book – close or far, all the inhabitants of the buildings are linked to the rich amateur painter and his aquarelle puzzles. A brillant idea.

In Spain, I’m going to Algeciras, just in front of Gibraltar. It is exactly two thousand years ago that the Gibraltar rock became a British colony, and also exactly a century that not so far from here Admiral Nelson defeated the French navy at Trafalgar… On va fêter ça!

Posted by len. on 28/7/2004, 17:40:52

Pierre asks:

>the descriptions

>the catalogues

>the stories

>the “mainstream” story of Bartlebooth and his Great Project

I love this book! Thank you ever so much for suggesting it.

There is a genre of book of the form “The Annotated …”, as in “The Annotated Alice”, “The Annotated Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea”, “The Annotated Wizard of Oz”, wherein the annotator footnotes every obscure and not so obscure detail of a book with explanatory material that reveals the things contemporary or local readers would know of that later or remote readers might miss.

This book cries out for an annotated edition.

Posted by Guillermo Maynez on 29/7/2004, 12:36:01

I also love this book so much and also thank Pierrre for suggesting it. It has enriched my French beyond months of classes.

The descriptions: wonderful in general, especially Mme. Moreau’s salle a manger, designed by Henry Fleury.

The catalogues: liked them, only I also skipped the tools one

The stories: fascinating, we’ll talk later about our favorite ones

The characters: intriguing.

As soon as I’m finished I’ll post several longer comments on this great book, one of the best we’ve read in our Book Club. Have a great vacation in Spain and try to check the site once in a while to follow our discussion about the book you recommended.

~

Posted by Lale on 4/8/2004, 10:08:21

I am reading this book mostly for the beauty of the descriptions and the weirdness of some of the events (trapeze artist living his life on the rope and then, when forced to come down, jumping to his death, for instance.)

All my life, for as long as I could remember, I have been fascinated by windows. In my childhood, when my parents took me out for a ride in the car or when we went out for a walk, I never spoke to anyone during the entire time of the trip. I just looked at the windows. It was/is not to see what is inside. Not complete voyeurism. I look at the windows to see

1. How the window itself and the window decorations presented the life inside, how much of the life inside they displayed, at what angle, at what percentage.

2. To get a glimpse of some of the life that is going on inside (as revealed by the certain angle available to me as I pass by) and to imagine the rest. (Partial voyeurism)

I never stare at a window. I just look at it as I pass by. I am known to bump into telephone poles while I walk, since my head is turned upwards to the higher windows of apartment buildings.

Windows provide me with so much imagination. The mere decoration of a window fascinates me. This one particular house in my town has a big, antique rocking horse at the window. It has been always been there. I think about the life in that house often. That wooden horse that decorates the window, what will happen to it when the owners pass away?

“La vie mode d’emploi,” provides me with a lot of window scenes. It is like I am passing by and I see the family Réol getting ready for dinner, the kid on the floor, playing.

It is amazing. So many windows. Some things revealed in great detail, some things hidden.

I love it.

Lale

~

Posted by Christopher on 5/8/2004, 12:05:28

Like Lale, I haven’t finished the book, and I probably wont. Rather than trying to solve the puzzle, I started admiring the individual pieces and skipping around on the over-sized chess board of Perec’s novel a little like a tourist without a road map. (The chess analogy is not entirely innocent – apparently Perec moves through the 10 x 10 grid of his apartment building like a bishop (ie. each chapter is removed diagonally in some way from the last, and there are two bishops) – I read this somewhere – don’t ask me to connect the dots!

I thought the lists were funny – and obsessively daring: I can’t imagine many authors would have the gall to list off an entire catalogue! The lists and the minute description all added to the supreme tension of this novel: the fine balancing act between the possibilities that the form and the content are at once both artificial and ultra-real. Throughout the novel Perec presents everything as if it were real, scientific, historic, actual – catalogues, bibliographies, family trees, etc. But in fact, even the bibliographies are false containing names of books that the author has invented. 11 rue Simon le Corbellier seems real enough, but of course, verification on the map shows that it doesn’t exist. Even the premise that we are looking into 99 windows seems realistic enough as a formal device, but it is only the concrete manifestation of a theoretical and mathematical model Perec wishes to exert upon his writing.

Apparently, there is a “book of constraints” that Perec used in composing this novel where he set out a very specific plan for each chapter where he could only write about certain things (reminiscent of the constraint of not using the letter “e” in La Disparition). I think that an annotated version would turn this novel into 4 times its length – but it would be an enlightening read. It’s really a fascinating book.

~

Posted by Rizwan on 5/8/2004, 16:51:51

I haven’t read the book, unfortunately. I just wanted to say, Lale, how much I enjoyed reading your little digression on windows–a bit of a window unto your soul, I think.

~

Posted by Guillermo Maynez on 5/8/2004, 15:43:34

Well, I have finished the book and I was left totally satisfied with the reading experience. I don’t care much for Perec’s games, schemes and clues, I simply enjoyed it straight through (and in French). The stories are unforgettable, the humanity that shines through is totally believable. Perec’s main message seems to be: life has infinite possibilities, we can never know how things will turn out, life is a box of wonders. The descriptions were sometimes exasperating, but essential to put us right there with real humans in real rooms. The catalogues were fascinating and I think I missed much of the hidden clues, quotes and references, but anyway I am a reader, not a researcher. Of course I would check out any annotated edition that may come to life, because I would like to know more about clues and messages, but for now I have taken it simply as a wonderful peek into other people’s lilves (which is much of what literature is about anyway).

To start our discussion, I think it would be fun to know what everybody’s favorite stories were. Here are mine:

1. Of course the great saga of Bartlebooth and Smautf roaming around the world, painting acquarelles of seaports. I would love to take that trip but I am not a zillionaire (sigh). And the sequel, with the art critic whose life is ruined by his enterprise (and nice criticism of modern tourism)

2. The story of the guy who wouldn’t come down his trapeze (surrealistic)

3. The story of the incomprehended anthropologist (stupid white men)

4. The story of the beautiful Italian girl and the chemistry professor (sad)

5. The story of the Polish girl in love with the Tunisian (blame it on religious fanaticism)

6. The story of the two bicycle racers and the sister of one of them (marvelous)

7. The story of the chef who leaves his wife to be an actor (tragic)

8. The story of the Altamonts, the abortion and the resentful daughter (ugly)

9. The story of the Swedish diplomat whose baby and wife die and then he chases the murderer and kills her (Mme. de Beaumont’s daughter)

10. The story of M. Marcia the autodidact in art (great)

11. The story of the woman who made the devil appear (crazy)

12. The story of the European princess seized by pirates (romantic)

13. The story of the man who bought the Vase of Passion (legendary)

14. The story of the Reols and their fight for survival after buying an expensive bed (absurd)

15. The story of Mme. Moreau and her success in business (and her dining room).

~

Posted by Lale on 11/8/2004, 10:40:15

: 13. The story of the man who bought the Vase of Passion

This is my favourite story so far.

The book (using the term “book” loosely) I read just before Perec’s User Guide was the rubbish titled Da Vinci Code. It is one of those books that is entertaining but you can’t help being annoyed at the childish style, being insulted with the stupidity you are supposed to believe and thinking you are wasting your time. You feel a little guilty. It will, however, make a fun movie, an exciting action-mystery. I wouldn’t have felt guilty watching the movie because it’s only two hours whereas the investment that goes into the book is more like 12 hours.

Anyway. Right after reading that book, I read Perec’s short story about James Sherwood who becomes the victim of a very elaborate swindling scheme and pays one million dollars to buy what he is convinced to be the Holy Grail (also the topic of Da Vinci Code). Fantastic story. Fantastic writing.

~

Posted by len. on 11/8/2004, 11:18:25

Lale writes:

>Right after reading that book, I read Perec’s short story about James Sherwood who becomes the victim of a very elaborate swindling scheme and pays one million dollars to buy what he is convinced to be the Holy Grail (also the topic of Da Vinci Code). Fantastic story. Fantastic writing.

Which also would make an excellent movie!

~

Posted by Lale on 11/8/2004, 11:39:56

: story about James Sherwood who becomes the victim of a

: very elaborate swindling scheme and pays one million

: dollars to buy what he is convinced to be the Holy

: Grail (also the topic of Da Vinci Code). Fantastic

: story. Fantastic writing.

: Which would also make an excellent movie!

It would make a much nicer movie actually. The details of the whole con scheme could be turned into a smart and exciting script.

~

Posted by len. on 11/8/2004, 14:02:53

Lale replies:

Ok, let’s cast it.

What role does Johnny Depp play?

len.

~

Posted by Lale on 11/8/2004, 15:19:49

: Ok, let’s cast it.

: What role does Johnny Depp play?

In this particular movie, all our favourites will be the villains. Johnny Depp is Mandetta (sp?), the history student. Prof. Shaw will be Ed Norton. The other professor who shows up briefly at the end will be Sean Connery.

The victim, James Sherwood, well, that’s a tough one. How’bout John Travolta?

~

Posted by len. on 12/8/2004, 8:06:39

Lale suggests:

>The other professor who shows up briefly at the end will be Sean Connery.

You mean the bogus President of Harvard, Michael Stefensson? I was thinking Anthony Hopkins.

>The victim, James Sherwood, well, that’s a tough one. How’bout John Travolta?

I offer Gene Hackman.

Who plays the librarian, Jacob Van Deeckt? And the Italian workman, Longhi? And do we work Ursula Sobieski, who’s researching the story, into the film, as the narrator?

And who directs? I nominate Clint Eastwood.

~

Posted by Lale on 12/8/2004, 8:58:38

: You mean the bogus President of Harvard, Michael

: Stefensson? I was thinking Anthony Hopkins.

If we can’t get Sean Connery, we’ll settle with Anthony Hopkins.

: >The victim, James Sherwood, well, that’s a tough

: one. How’bout John Travolta?

: I offer Gene Hackman.

No good. Too old for the role. Sherwood is in his 50s.

Of course Sherwood (Travolta) will have the last laugh. We’ll see the swindlers in Argentina as they try to pass the fake 20 dolar bills.

: Who plays the librarian, Jacob Van Deeckt? And the

: Italian workman, Longhi? And do we work Ursula

: Sobieski, who’s researching the story, into the film,

: as the narrator?

I don’t know about the first two but since this is a Hollywood movie, Ursula (i.e. a girl, a beautiful author/researcher girl) will have to be in it. I guess the movie will start with her at 11 Rue Simon-Cubellier and end with her.

We have the whole script, now who is making the pitch to Hollywood?

~

Posted by Lale on 12/8/2004, 9:09:15

: 3. The story of the incomprehended anthropologist

: (stupid white men)

Is this the one about the guy who went to Malay in search of a tribe who didn’t want him and kept running away from him deeper and deeper into the woods? That was a very good story. How did Perec come up with these things? He was a genius. Last night, to hubby, I declared User’s Manual one of the most amazing books I read in recent memory.

~

Posted by Lale on 14/8/2004, 19:51:49

: 9. The story of the Swedish diplomat whose baby and

: wife die and then he chases the murderer and kills her

: (Mme. de Beaumont’s daughter)

This guy was the maddest character I have ever come across in a book.

~

Posted by Lale on 10/8/2004, 8:45:04

: Friends: keep the apartment building stories coming,

: but I’m still waiting to know which stories you liked

: the most in Perec’s book.

I am still at the one fifth mark, so I can’t decide yet. There are still many stories to come I am sure. But I love the friendship between Winckler, Valene, Morellet and Smautf. I also love the general kindness and support most of the un-rich and un-famous residents show one another. You notice how they have a bond? Whereas the more accomplished, wealthy and famous you are the more you are removed from the neighbors.

The friendship in the apartment reminded me of the friendship in the ghetto in The Golem, between the main character and his drinking buddies.

~

La Vie… The 51st Chapter

Posted by len. on 16/8/2004, 7:49:27

I need some corroboration from our colleagues with the French edition.

In my (I believe to be excellent) English translation, all the chapters except the 51st are headed “Chapter xx”; the 51st chapter however, is headed “The 51st Chapter”. Chapter 51 contains a 179 item list, set in a fixed width (non-proportional, typewriter-like) font, with each line being exactly 60 characters in length, including punctuation. The 179 lines are grouped in three sets of 60, 60 and 59 lines (no MIT jokes, Lareina already got me on that).

These 179 lines are brief “snapshots” from the numerous stories scattered throughout “La Vie…”.

In the first group, starting with the last letter of the first line, the next to last letter of the 2nd line, the 3rd letter from the end of the 3rd line, the 4th letter from the end of the 4th line, etc., to the first letter of the 60th line, are all the letter “e”.

In the second group, the same descending right to left diagonal pattern is repeated with the letter “g”.

In the third group, one line short, the same diagonal pattern is repeated with the letter “o”.

And the first letter of Chapter 52 is, of course, “O”.

The snapshots are occasionally rendered is slightly odd or stilted English, in order to achieve this effect, but the clauses are all grammatically correct and recognizable as describing moments from elsewhere in the book.

What does the original French look like?

And would anybody care to hypothesize as to the meaning of this gesture?

Posted by Lale on 16/8/2004, 10:33:10

You are 60 pages ahead of me.

In the French edition, all the chapters are titled CHAPITRE XX, like in the English version. Chapter 51 is titled LE CHAPITRE LI, i.e. with the addition of “the” at the beginning. So, the chapter is definitely marked for difference.

: In the first group, starting with the last letter of

: the first line, the next to last letter of the 2nd

: line, the 3rd letter from the end of the 3rd line, the

: 4th letter from the end of the 4th line, etc., to the

: first letter of the 60th line, are all the letter “e”.

These seem to be all letter “a” in the French version:

Covadonga

Amsterdam

étage

de sable

un cahier

de jacquet

absents

à Bécaud (here we notice that a space counts as one character)

la bigamie

la campagne

à son roman

australienne

etc.

: In the second group, the same descending right to left

: diagonal pattern is repeated with the letter

: “g”.

In the second group, French version has “m”

quartre-vingt-huit m

de gomme

Fitz-James

sa chambre

tour du monde

etc.

: In the third group, one line short, the same diagonal

: pattern is repeated with the letter “o”.

In the third group it is the letter “e”.

nécrologique

Kléber

recteur

Pirandello

So we have A-M-E. If it is of indication of anything, “âme” means “soul”.

: And the first letter of Chapter 52 is, of course, “O”.

First letter of chapter 52 is “U”, so, nothing there. (“Une des pièce de l’appartement des Plassaert …”)

I would have never noticed this last letter (and then diagonally from there) business had you not mentioned it. How did you notice it? Are they highlighted in your version, like I did here?

: And would anybody care to hypothesize as to the meaning

: of this gesture?

I think Perec is just showing of his craft here. Remember the chess board thing Chrsitopher mentioned? Something like that I suppose. This is the guy who wrote an entire book without the letter “e”.

Lale

~

Posted by Christopher on 16/8/2004, 10:42:23

: In the first group, starting with the last letter of

: the first line, the next to last letter of the 2nd

: line, the 3rd letter from the end of the 3rd line, the

: 4th letter from the end of the 4th line, etc., to the

: first letter of the 60th line, are all the letter “e”.

In the French original, the same pattern exists but the letter is “a”

: In the second group, the same descending right to left

: diagonal pattern is repeated with the letter “g”.

In the French original the letter is “m”

: In the third group, one line short, the same diagonal

: pattern is repeated with the letter “o”.

In the French original the letter is “e”

: And the first letter of Chapter 52 is, of course, “O”.

In the French original the chapter starts with the letter “U”, so no relationship.

: And would anybody care to hypothesize as to the meaning

: of this gesture?

So the obsessive letters in Chapter 50 “ame” spell “soul”. Just like the English spells “ego.”

As for the third group being “one line short”: it seems pretty typical of the novel were everybody’s projects are never entirely completed.

~

Posted by Christopher on 16/8/2004, 10:45:28

Lale has beat me to it.

My E-G-O is crushed.

~

Posted by Lale on 16/8/2004, 10:48:02

So, why do you think he titled this chapter “Le Chapitre LI”?

(Just giving you a change to rebuild your E-G-O.)

Lale

~

Posted by len. on 16/8/2004, 11:24:35

Lale asks:

>I would have never noticed this last letter (and then diagonally from there) business had you not mentioned it. How did you notice it. Are they highlighted in your version, like I did here?

No highlighting. My curiosity was piqued by the change in font. Soon I realized that the lines were all the same length, as measured by number of characters, because they had the same physical length in the fixed width font.

Then, quite by accident, I noticed the subtle visual effect along the diagonal of the second group. This was due to the descender of the “g”; the effect is virtually invisible in the first and third groups (“e” and “o”). Examining the text more closely, I realized the diagonal was formed by the same letter.

I went back to the first and third groups, suspecting that the second group was not unique in this regard. I looked for things like vertical messages in columns of aligned characters. Eventually, I realized that the same diagonal scheme applied.

So, has anyone mapped out the path through the apartment layout that’s apparently implied by the chapter sequence?

Raskolnikov and Meursault meet in Hell

Posted by Lale on 20/8/2004, 14:16:28

Here is another pearl from Perec’s “La Vie”:

There are two people in the waiting room. One is an extremely thin old man, a retired teacher of French who still gives tuition by correspondence, and who whilst waiting his turn is correcting a pile of scripts with a pencil sharpened to a fine point. On the script he is about to examine, the essay title can be read:

In Hell, Raskolnikov (Crime and Punishment) meets Meursault (“The Outsider”).

Imagine a dialogue between the two.

~

Life A User’s Manual – Wrapping Up

Posted by Lale on 30/8/2004, 12:12:54

I finally finished the book. Gosh it was a big book. It was much harder to read than all the other big books because of thousands and thousands of names and characters. I had to do a lot of re-reading. By the time I reached “Louvet 2” I had already forgotten about “Louvet 1” so I had to go back and read it again.

Anyway, it is finished now. What a book! What fascinating stories! And so many of them! I don’t think it is possible to count all the mentions of all the characters but the significant ones are listed at the back of the book and they add up to 107 (106, excluding Mark Twain).

Just as a reminder, this was Guillermo’s list:

~ 1. Of course the great saga of Bartlebooth and Smautf roaming around the world, painting acquarelles of seaports. I would love to take that trip but I am not a zillionaire (sigh). And the sequel, with the art critic whose life is ruined by his enterprise (and nice criticism of modern tourism)

~ 2. The story of the guy who wouldn’t come down his trapeze (surrealistic)

~ 3. The story of the incomprehended anthropologist (stupid white men)

~ 4. The story of the beautiful Italian girl and the chemistry professor (sad)

~ 5. The story of the Polish girl in love with the Tunisian (blame it on religious fanaticism)

~ 6. The story of the two bicycle racers and the sister of one of them (marvelous)

~ 7. The story of the chef who leaves his wife to be an actor (tragic)

~ 8. The story of the Altamonts, the abortion and the resentful daughter (ugly)

~ 9. The story of the Swedish diplomat whose baby and wife die and then he chases the murderer and kills her (Mme. de Beaumont’s daughter)

~ 10. The story of M. Marcia the autodidact in art (great)

~ 11. The story of the woman who made the devil appear (crazy)

~ 12. The story of the European princess seized by pirates (romantic)

~ 13. The story of the man who bought the Vase of Passion (legendary)

~ 14. The story of the Reols and their fight for survival after buying an expensive bed (absurd)

~ 15. The story of Mme. Moreau and her success in business (and her dining room).

Of course the story of Bartlebooth and Smautf is the most fascinating one since it spans over 50 years, and one of the saddest ones. No matter how useless Bartlebooth’s project was, I wanted for him to finish it. I found it very heartbreaking that he couldn’t. After so many years of devotion.

I associated with many of the characters in the book because of their unsuccessful or useless or unfinished projects. I have such projects myself. (“La Seine et ses ponts”, as some of you know, is one).

I found these ones very original therefore very captivating:

~ 2. The story of the guy who wouldn’t come down his trapeze

~ 3. The story of the incomprehended anthropologist

These ones I truly loved:

~ 13. The story of the man who bought the Vase of Passion

~ 10. The story of M. Marcia the autodidact in art

~ One that is not mentioned by Guillermo: Cinoc whose name has corrupted from Kleinhof and who works for Larousse to erase obsolete words and names. Or as the list at the end of the book calls him “a word-snuffer”.

~ 14. The story of the Reols and their fight for survival after buying an expensive bed ~ This story was hilarious. The way poor Reol wants to get hold of an appointment with the head director and the way the director keeps making himself absent all the time. It reminded me Aziz Nesin’s stories (see “The Reference Card” under Turkish Literature)

I thought this story was very sad:

~ 8. The story of the Altamonts, the abortion and the resentful daughter

The letter Veronique (the daughter) finds was one of the most beautiful writings I’ve ever read. The father’s story (Cyril Altamont) was very heartbreaking. He tells it so beautifully. And ends it with:

“I have stopped wondering whether it is hate or love which gives us the strength to continue this life of lies, which provides the formidable energy that allows us to go on suffering, and hoping.”

This story is the story of sheer madness:

~ 9. The story of the Swedish diplomat whose baby and wife die and then he chases the murderer and kills her (Mme. de Beaumont’s daughter)

And I really enjoyed:

~ The Columbus/Vespucci story.

There are probably others that I can’t think of right now. There were so many. It is definitely a book to read over and over again. It is impossible to grasp all of it in just one run.

~

Life A User’s Manual – A few puzzles

Posted by Lale on 30/8/2004, 12:25:22

These are easy enough:

~ Prudence is 24 years of age. She is twice as old as her husband was when she was as old as her husband is. How old is her husband?

~ Write the number “120” using four eights.

~ Which is the odd item in the following list: French, short, polysyllabic, written, visible, printed, masculine, word, singular, American, odd?

This next one seems obscure and I am finding it tiring to consider it. It’s just something you see immediately or you never see, I suppose:

~ What comes after O T T F F S S E? (must be related to the meanings of the words since the sequence in French is different: U D T Q C S S H )

~

Posted by len. on 30/8/2004, 13:17:28

Lale asks:

>What comes after O T T F F S S E? (must be related to the meanings of the words since the sequence in French is different: U D T Q C S S H )

One – Un

Two – Deux

Three – Trois

…

Nine – Neuf

~

Posted by len. on 30/8/2004, 13:37:53

>Prudence is 24 years of age. She is twice as old as her husband was when she was as old as her husband is. How old is her husband?

18

>Write the number “120” using four eights.

8 * (8 + 8) – 8

~

Posted by len. on 30/8/2004, 13:12:50

Lale notes:

>One that is not mentioned by Guillermo: Cinoc whose name has corrupted from Kleinhof and who works for Larousse to erase obsolete words and names.

What I want to know is why the enumeration of possible pronunciations for Cinoc dismisses the “k” sound for the initial “c”.

~

Posted by Lale on 30/8/2004, 15:14:52

: What I want to know is why the enumeration of possible

: pronunciations for Cinoc dismisses the “k”

Because they are stuck on the “i” that follows the “c”. In French, there is no way you can pronounce a “c” like a “k” if it is followed by an “i”. The same with an “e”.

If the “c” was followed by an “o”, “u” or an “a”, then “k” pronunciation would have been possible.

~

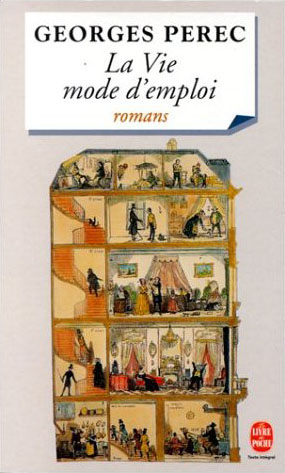

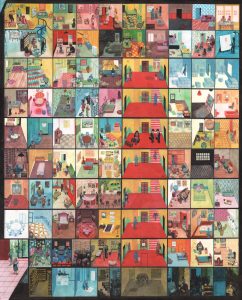

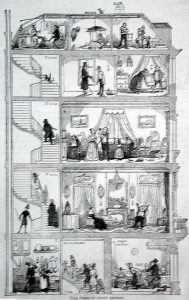

Do you know anything about the painting/gravure as seen on the cover of La Vie mode d’emploi published by Le Livre du Poche? At the back of the book, this information is provided:

Couverture: Lavielle, 5 étapes du monde parisien. Photo Hubert Josse.

That’s it. Nothing else. It doesn’t give the full name of the artist, Lavielle; and there are plenty of Lavielles on internet. I did find some gravurists named Lavielle but nothing that would lead me to 5 étapes du monde parisien. The back cover of Le Livre du Poche doesn’t say where the gravure/painting is, whether it is in a museum or in collection particulière. Nothing. Searches on Hubert Josse didn’t get me anywhere non plus. All I want is to be able to find where the original of this work is. Hopefully it is in a museum so I can go and see it. Maybe even buy a print of it. I did not leave any stone unturned on the internet and I came up with nothing. Can anyone help me on this one? Do you know the full name of the artist and/or where the original of this work might be displayed?

The only thing I could find on the internet was this:

Coupe d’un immeuble parisien du 19e s.

As you can see, the title of the work here seems to have a different version: 5 étages du monde parisien, i.e. étages and not étapes. Also, it seems to be from a book which talks about Azor et Babet which also failed to lead me to some place useful.

I would very much appreciate any pointers. If you know anything about Lavielle or 5 étapes du monde parisien, please write to readliterature.com

~

Posted by Eric 16/12/2004, 15:34:05

Hello:

I just finished reading life a user’s manual and readily admit that I did not “get” the majority of the clever-osities. In fact the only thing I noticed was that there was a play on words with Italo Calvino’s name in the chapter 51 list (English version).

Certainly the book stands on its own, but I’m very interested in knowing about all the references and also understanding the OULIPO constraints adhered by Perec.

Do you guys know of ANY resource that sheds some light on the book? It would be much appreciated.

Eric

~

Posted by Lale on 16/12/2004, 15:49:27

Eric,

Most of us here read the book and we all loved it. But I doubt very much that we got even 50 percent of all the references and symbols.

OULIPO (OUvroir de LItterature POtentielle) must be mainly for the native French speakers. Even when it is accessible to us, non-francophones, I don’t find it particularly enriching or pleasurable. The idea is to put restrictions on your writing, such as an entire book without the letter “e”…

In “Life: A User’s manual”, there is a chapter in the middle that lists the beginings of the synopsis of all the other chapters with certain letters (a, m, e in French and e, g, o in English) forming a diagonal line. Yes, it is hard to do but what does it give to me, the reader? It is just the writer amusing himself, giving himself some challenges, solving puzzles. It is fun for him. OK, it may also entertain the reader for a second or so, but largely it doesn’t do much for the reader.

In any case, “Life – A User’s Manual” remains one of the best books I have ever read because of thousands of characters I met and thousands of little stories (each more original than the other) I read.

Lale

~

Posted by Eric on 16/12/2004, 16:52:56

I totally agree that even without insight into Perec’s tricks/references, there’s still a lot of amazing stories in the book and it’s a very worthwhile read. But I am definitely intrigued to learn more.

In an early synopsis (12?), he twice references Calvino – once with the phrase “bitter local vino” and again with something about the island of “…calvi, no…” (Sorry for the imprecise quotes – I don’t have the book in front of me).

What does that mean? Is there a story in the style of Calvino? Is there a story written by Calvino (a bit of a stretch, I know)? And are the other author names hidden in the other synopses?

I’m sure even this line of questionning is scratching a crystal on the snowflake at the tip of the iceberg. I would gladly read an annotated version of Life (which one of your book club members surmised would probably be 3x as long as the book itself).

~

Posted by Eric on 17/12/2004, 7:01:40

FYI – The calvino references are not in the 51st chapter but rather Chapter 59 (Hutting), painting number 8.

My bad.

~

Posted by Lale on 17/12/2004, 10:46:25

I think some of the references were made without a hidden meaning. In Georges Perec’s case, yes, most references had a deeper meaning, as we can generalize from the chess board movement from one apartment to another; or from the puzzle Christopher solved (or found the solution for), “Quelle est la menthe qui est devenue tilleul? qui surmonte le chiffre 6 dessine artistiquement.”:

la menthe = amante

le chiffre 6 dessine artistiquement = beau 6 = Baucis

After their wishes Baucis and Philomene were wrapped eternally in a linden tree = tilleul.

However, I do think authors do make insertions just for the sake of making the story more interesting, or making it sound more pretty, without hidden agendas. Not everything is associated with something else. Sometimes it is just plain name dropping. We (all readers) have this problem with Yann Martel’s “Life of Pi”. The book is full of symbols, yes, but as it turns out, readers are now finding symbols that were never intended by the writer. I guess once we realize that there are symbols we start looking for them every where.

As for Calvino, Perec and Calvino were contemporaries. Maybe there were some insider jokes amongst the artists of the day. We cannot possibly uncover everything. Some things were just in the creators’ minds.

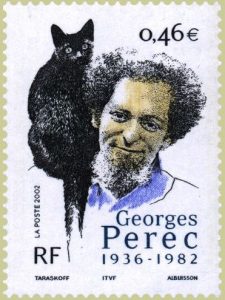

Here is an interesting excerpt from a Perec biography from the net (the original link no longer works, so I am posting from a saved text):

Perec made his debut as a novelist with Les Choses (1965, Things), which won the Prix Renaudot. In 1967 Perec joined the Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (OuLiPo), a group of writers and mathematicians founded by Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais. OuLiPo became Perec’s intellectual home. The group devoted to exploring the creative potentials of formal rules, and specialized in anagrams, palindromes, mathematical word games, and other puzzles. Under their influence Perec produced La Disparition (1969, A Void, translated by Gilbert Adair), a detective novel in which the central puzzle deals with the disappearance of the e from the alphabet. This artificial literary world doesn’t know she or he or sex, but manages to create an alternate view on reality. “Understand too much of this book and you die: Any full and final form of illumination is blinking at us, winking at us, just out of our sight, just out of our grasp. That’s the frolic in it — we never get there, which means that the fun never ends, not really, not unless we yearn too much for the secret of E.” (James R. Kincaid in The New York Times, March 12, 1995) La Disparition was followed by Les Reventes (1972), which was written without the vowels a, i, o, u, but contained e. Espèces d’espaces (1974) examined spaces around and outside us, from one’s bed to the universum. His starting point was how letters, words, and lines fill a blank sheet of paper, forming a kind of space: “before, there was nothing, or almost nothing; afterwards, there isn’t much, a few signs, but which are enough for there to be a top and a bottom, a beginning and an end, a right and a left, a recto and a verso.”

W ou le souvenir d’enfance (1975, W or the Memory of Childhood) is an exceptional Holocaust narrative, in which chapters of childhood memories alternate with chapters of a fictional story. “I have no memories of childhood,” Perec wrote. He compares his isolated memories with photograps, and imagines comforting scenes from his unfulfilled childhood: “As for me, I would have liked to help mother clear the dinner from kitchen table. There would have been a blue, small-checkered oilcloth on the table, and above it, a counterpoise lamp with a shade shaped almost like a plate, made of white porcelain or enamelled tin, and a pulley system with pear-shaped weights. Then I’d have fetched my satchel, got out my books and my writing pad and my wooden pencil-box. I’d have put them on the table and done my homework. That’s what happened in the books I read at school.” The fictional material consists of a story of a false identity and a dystopia set on an island called W, somewhere off Tierra del Fuego. Aryans have created on the island a totalitarian society. It based on a bizarre conception of sports, in which men are separated from women, children from their mothers, and losers receive grisly punishments. In the end the two complementary narratives unite when Perec refers to a book, which describes how sporting competition was developed in concentration camps into a vehicle of destruction.

Life: a user’s manual was awarded the prestigious Prix Médicis. It has over 100 interwoven stories which concern the inhabitants of a large Parisian apartment building situated at 11 rue Simon-Crubellier. The structure of the novel is governed by chessboard of ten squares by ten, knight’s moves, and algorithms. The building was inspired by a Saul Steinberg drawing of a New York apartment house with its façade removed. One of the characters is Percival Bartlebooth, an English millionaire, who decides to bring artistic and formal control of his life to its outermost limits: he would study watercolor painting with Serge Valene for ten years, then he would travel the world for 20 years and paint pictures of different ports. The watercolors are cut into jigsaw puzzles in Paris. The rest of his life-plan, 20 years, Bartlebooth reassembles the jigsaws, which finally are dipped into a detergent solution until nothing else is left but a blank paper. However, Bartlebooth dies before he has finished all 500 of his jigsaw puzzles.

~ ~ ~

Perec’s Life – A note from the translator, David Bellos

Let me first say how delighted I am to see all you keen readers delving into such a wonderful book – the six months I spent translating it were the most intensely enjoyable of my life.

The engraving you’re inquiring about began life in the 1830s as a drawing by a fairly famous artist of the time called Bertall, and the drawing was titled “Une Maison bourgeoise”. It has been re-used many times since in many ways, but maybe most notably as a jacket illustration (and as a kind of “explanation”) for Balzac’s novel Père Goriot, roughly contemporary to the original drawing, and, like Perec’s novel, set in an apartment house in central Paris and devoting a lot of space to descriptions of the different rooms. Note that in the 19C the “noble floor” is the first (sorry, that’s European – in US you say second) and that the paupers and artists live in the attic (penthouse).

It was Perec’s decision to re-use it for the paperback reprint of Life (the first edition, like most French “literature”, had no illustration, just a tombstone jacket). But it was in black and white. The colored (and slightlyl amended) version was done in 1980-81 for the German translation, and has been purloined by numerous other publishers since then (including the British, Turkish, Greek, and Brazilian editions).

Voilà

David Bellos

~ ~ ~

Still from David Bellos, a post script

Re: Perec, Life, Chapter 51, acrostic, French text

I regret to inform readers that the brilliant demonstration of the regularity of the first 60 lines of the “Compendium” is the fruit of a little delicate cheating by your amateur (but no doubt zealous and devoted) typesetter. Three of the lines of Perec’s French original do not quite fit. I leave the typist to own up to the improvement s/he made in copying the thing out.

The question will then arise: why mistakes? why these mistakes?

~ ~ ~

David Bellos

From Princeton Universities web site:

DAVID MICHAEL BELLOS (D.Phil, Oxford) is Professor and chair of Romance Languages and Literatures and Professor of Comparative Literature. He has taught at the universities of Oxford, Edinburgh, Southampton, and Manchester (England), where he served as head of the department (1985-1988) and as chair of the Graduate Studies Committee (1992-1996). He has published three books in the field of Balzac studies (Balzac Criticism in France, 1850-1900, Oxford, 1976; a critical study of La Cousine Bette, London, 1981; and an introduction to Old Goriot, Cambridge, 1987) as well as many articles on the history of fiction and the book market in 19th- century France. More recently he has concentrated on the modern French writer Georges Perec, first as his principal English translator (Life A User’s Manual, 1987, which won the French-American Foundation’s translation prize in 1988; W or the Memory of Childhood, 1988; Things, 1990; 53 Days, 1992) and then as the author of the first literary biography (Georges Perec. A Life in Words, Boston, 1993) which in French translation, was awarded the Prix Goncourt de la Biographie (1994). He is also the translator of novels by the distinguished Albanian writer, Ismail Kadare. His biographical study of the French filmmaker Jaques Tati appeared in Fall 1999 in the United Kingdom and is expected to appear in French translation in 2001. David Bellos holds the rank of Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Palmes Académiques.

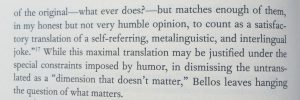

Criticism of David Bellos’s translation of Life / La Vie, by Emily Apter (Against World Literature: On the Politics of Untranslatability, Verso, 2013, Introduction, pages 18-20)

![]()

The related page (in which the German Lieder business card is found) in Life A User’s Manual is 270 in the Verba Mundi / Godine edition, 2009.