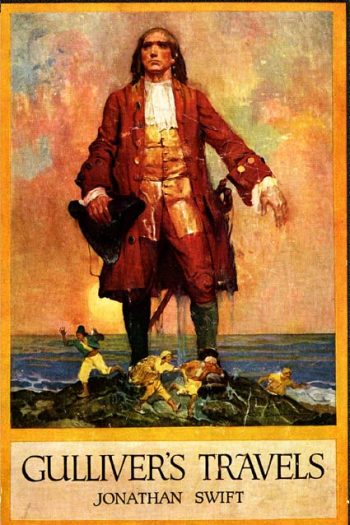

Gulliver’s Travels – Jonathan Swift – 1726

Reviewed by: Michael Sympson Date: 26 September 2001

Giants, midgets, cobwebs and the moons of Mars. Allow me to quote:

Giants, midgets, cobwebs and the moons of Mars. Allow me to quote:

“There are unquestionably people who won’t appreciate Swift’s style but there will also be people who don’t appreciate good food, good drink and healthy exercise–all you can do is leave them to their folly and continue apace. No English language writer has ever matched Swift’s chainsaw tongue. His misanthropic rage, vented in Gulliver’s Travels, hacks away at the tender, maggoty, easily severed parts of pretense and hypocritical morality.

“Nor does Swift anywhere ask for quarter, as he gives none. Those who don’t like his reading are free to continue in their superficiality or their ignorance, and his definition of satire–a looking glass in which people see every face but their own- remains the definitive statement of the art. Swift’s lessons on writing are also direct and easy to grasp: write simply. His acid wit eats through everything it touches: academia, politics, literature, modernism…it’s a bitter pill, especially if you are one of the few who sees your own face in the mirror.” Seth Davidson (who is this guy?)

I couldn’t have said it better. Swift’s novel is a marvel of the language and a universe of its own. And sometimes, this clearest of all English writers could be completely enigmatic. Or how are we to explain that Asaph Hall discovered the two sattelites of Mars in 1877, but we read a discription of the planet’s companions as early as 1727, the year when Richard Sympson, (yeah, yeah, the Sympsons) published Samuel Gulliver’s travel account. How could the author possibly know?

Well he knew of course Newton’s physics, it was the talk in polite society, and it was long known that the total mass indicated by Mars’ trajectory did not quite tally with observation. The introduction of better optical instruments finally solved the riddle. So Swift took the liberty of a very educated guess. And this coming from the same guy who so hilariously poked fun on the Royal Society of Sciences!

The University of Lagado is undoubtedly the heart of the book. Imaginative writing at its best. Swift is almost always intriguing. The exchange of material tokens to replace the spoken word is not an entirely implausible proposition for a theory of language. The random computer to establish literature from scratch is an ongoing project in our days. Reclaiming nutrient’s from stool would make a Captain Kirk proud. And what’s so special about artificial fibre with the properties of spiderwebs? (For nylons?) Done that, been there!

Dr. Johnson was a great man and a good man, but not entirely free of envy. So we have to take his comments on Swift and Sterne with a pinch of salt. Of course it is true, the idea to place the novel’s protagonist first among midgets and then giants with all its satirical potential and political needling is really easy to do, once the method had been discovered. Well, nobody was stopping you, Sir, to do likewise. Anyway, somebody is always the first, and the rest of us can only applaud. Let’s rise for a standing ovation.