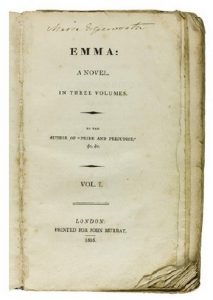

Emma – Jane Austen – 1815

Reviewed by: Gretchen Date: 6 January 2005

As with all of Jane Austen’s books, here are some lessons we could certainly learn even today.

Despite its romantic overtones, it teaches us the value of boundaries and the delusions that may occur because of vanity and social blindness.

Handsome rich Emma is the perfect English heiress who, in an effort to channel her energies, sets about matchmaking people and neighbors around her.

Her exasperated childhood friend Mr. Knightly warns her of the dangers in meddling, which will cause more harm than good by taking up with Harriet, a Boarder at a Girls school who the the natural daughter of an unknown gentleman.

Wrapped up in her visions of nobility and mission, she disregards the warning causing more heartache than help for her small friend.

Emma teaches us as people of power and influence that we have a social obligation to try to see the world the way those less fortunate do. We need the humility to crawl into their shoes and really see the world from their eyes.

Simply because we have good intentions to help, doesn’t mean we don’t have the responsibility to consider HOW we help. This is the true meaning of grace and nobility oblige that Emma learns in the end while falling in love herself along the way.

Many observations made by Mr. Knightly and Emma herself still hold true today which make this classic timeless.

~

Posted by Joffre on 12/10/2014, 19:45:54

While I did enjoy Emma very much, I also prefer P&P. I see this as the conflict between what we enjoy, which is highly personal, and what is greater, which I’ve always felt is impersonal. I’ve begun to understand what is greater as what has the most significance for the history of the novel. James Woods characterizes the history of the novel as the rise of detail and the development of free indirect style. While she might have picked up the device from Fanny Burney or Maria Edgeworth, Austen is considered the developer of free indirect style. John Mullan, in How Novels Work, calls it her most important contribution to the novel. In The Broken Estate, James Wood traces the development through her novels. It is almost non existent in Northanger Abbey and Sense and Sensibility. It is something like Shakespearean soliloquy in P&P. It comes earlier and more often in Mansfield Park. It is first used extensively in Emma.

I read Humphry Clinker a couple months ago and found it dull as hell.

~

Posted by Sterling on 12/10/2014, 23:02:01, in reply to “about Emma”

Well, I haven’t read Woods, so it isn’t really fair for me to launch a rebuttal. But if he really asserts that the development of the free indirect style is crucial to the development of the novel, then I don’t think much of him. Good God! What of all the wonderful novels written in the first person? If Austen was the first to use the FIS, then is the 18th century novel beneath consideration? What of the modernist styles that either go for extreme inwardness (Gass, for example) or pure surface (Robbe-Grillet)? What of the baroque stylings of the post-modernists that mock the traditional realist styles? I don’t believe that you can really speak of “progress” in art the way that you can with science and technology. If so, then a modern novel would be better than Austen, Dickens, or Joyce, just because it is newer. The idea that Emma is “greater” because it features more of the free indirect style strikes me as critic’s nonsense.

PS – I’m sorry to hear that you didn’t enjoy Humphry Clinker. Steven, Guillermo, and I enjoyed it very much when we read it September 2012.

~

Posted by Lale on 13/10/2014, 10:13:27, in reply to “Re: about Emma”

Sterling, while I agree with your general argument, I do think that the work that brings in some inspirational innovation needs to have a special place in history. It deserves acknowledgement for introducing a groundbreaking style which changes the way people write.

Most works that are considered “important” or “great” have brought in some original thought or style, the first “stream of consciousness” for instance. You also give good examples of this (Robbe-Grillet etc.); these examples confirm, as opposed to challenge, the greatness of a book which introduces a style that receives wide and long-lasting acceptance from readers, writers and critics.

In French, Albert Camus’ L’Étranger was the first book to use passé composé as opposed to passé simple. (Aujourd’hui, Maman est morte.) It deserves recognition for that.

I don’t think an innovation in art renders previous art work worthless. Even in science and technology, we continue to value and appreciate creations which have been surpassed by what came after them.

Lale

~

Posted by Sterling on 13/10/2014, 19:12:42, in reply to “Re: about Emma”

Well, okay, I don’t disagree with you, Lale. Stylistic innovation is indeed a big deal. Ulysses and The Sun Also Rises are stylistic milestones. I’m sure L’étranger is in French, as well. (Since I read only English, I’ll have to take your word for it. Hell of a good novel, though, even watered-down into English.)

I just find it difficult to credit Austen’s use of “free indirect style” as a major stylistic breakthrough. (And I rather think that Ms. Austen would be surprised, as well.) She is a wonderful stylist with great wit and precision. I think she has been very influential, but I doubt that other authors snatched up their copies of Emma and shouted, “My God! A free indirect sentence! Why didn’t I think of that? I believe I’ll use it in my next novel!” (I’ll leave that to the critics.)

~

Posted by Joffre on 13/10/2014, 20:10:53, in reply to “Re: about Emma”

I don’t think it’s about progress. It’s about influence. Before Austen there was not much use of free indirect style. David Lodge locates a few ‘brief, fragmentary examples in Edgeworth and Burney. After Austen it became so common we hardly notice it as new. After two hundred years, how could we notice it as new. Woods points out a passage in Mansfield Park where Austen moves from third person narration to first person soliloquy to free indirect style. He thinks this makes her a more radical novelist than even Flaubert.

Of course the 18th century is not beneathe consideration. Austen herself is using what she learned from Richardson, what was learned from Cervantes, etc. It is just that Austen made one of the most influential contributions like various writers before and after her.

And wouldn’t it rather mean that newer works could never be as great as the older books that made such important contributions.

It is great because it established a technique that has been so influential. That doesn’t necessarily mean there aren’t great novels that eschew the technique. The point is that Emma is Austen’s most influential book.

~

Posted by Sterling on 13/10/2014, 21:21:44, in reply to “Re: about Emma”

Okay, Joffre, I’ll let it go. I’m unconvinced that Austen was a “radical” novelist, stylistically or otherwise. (I think Flaubert was, although I’m hampered in my analysis of his style by my inability to read French well enough to appreciate style.) And I do agree that after two hundred years, it is difficult to recognize an innovation that has become thoroughly assimilated. (You have to compare The Sun Also Rises to a 19th or early 20th century novel to see how radical it is, since the journalistic style has become so ubiquitous in the modern mainstream novel that it seems unexceptional.) I just don’t really understand why it (free indirect style) is a big deal.

PS – Emma may be stylistically the most influential, but I would submit that a greater number of novels have been influenced by the content of the more beloved P&P.

~

Posted by Joffre on 14/10/2014, 20:13:08, in reply to “Re: about Emma”

You needn’t drop it. I’m not trying to silence you, though you may feel like it after this post, just to share some things that I found immensely interesting.

from The Cambridge Introduction to the Novel by John Mackay:

Free indirect discourse is probably the most common of novelistic techniques… a narrative strategy that lends itself brilliantly to ironic effects at the expense of a character…. Austen… pioneered free indirect discourse. The omnisciently narrated passage tells you… this passage of f.i.d. shows you.

The traditional prevalence of the coming-of-age narrative helps to explain the ubiquity of f.i.d. through the 19th century and beyond. This is a narrative strategy that is all about ignorance surmounted and knowledge difficultly attained.

…one of the 19th century forms that modernist writers of the 10s and 20s embraced and extended. Joyce’s PotAaaYM deploys third person narration, but always filtered through the consciousness of… Steven Dedalus.

from How Novels Work by John Mullan:

technique pioneered by Austen – odd as it may be to think of her as a technical innovator…. They (Fanny Burney and Maria Edgeworth) did not really discover its potential for combining both distanced observation of a character and a sense of how he or she sees the world. The technique, arguably her most important gift to later novelists is used most brilliantly in Emma. The technique has become so common we hardly notice it.

F.I.D. gets us immediately close to characters while keeping their deepest thoughts or fears unspoken. It is a means of concealment as much as disclosure. The use of f.i.d. to show how things are left unthought as well as unsaid is common. It is ironical that free indirect style is sometimes called free indirect speech when so often it allows unspoken assumptions to enter the narrative.

I’d like to quote a bunch of James Wood, but I feel this is already too much. I only wanted to give my explanation of why Emma is usually ranked first of Austen’s novels. Recall that it ranks considerably higher in Daniel Burt’s Novel 100. Even before I ever saw that list, I had read that Emma was Austen’s masterpiece. Yet P&P has been the “common reader’s” favorite. Critics make these lists and make them, I think, based on the historical import or the influence books have.

~

Posted by Sterling on 14/10/2014, 20:30:25, in reply to “Re: about Emma”

Okay, Joffre, I still don’t really get what it is. Is it the same as a third person limited narrative mode? It kind of sounds like it. I mean it’s apparently like giving a person’s thoughts without actually saying, “she thought.” And that’s this huge breakthrough? (Maybe this is why I never liked Lit courses. I only like reading the stories. I want to ride in the car. I don’t want to tear down the engine.)

~

Posted by Joffre on 15/10/2014, 11:36:35, in reply to “Re: about Emma”

I won’t beat you with it.

What can I say? I wanted to be a literature teacher. I quit graduate school because instead of teaching me what was well done or badly done in authors, instead of evaluating their writing skills and studying their influence on others, we were talking about whether or not they were racist or sexist. I’ve read lots of books like Kundera’s Art of the Novel, Forster’s Aspects of the Novel, Wharton’s On the Writing of Fiction. I enjoyed them all. When I read James Wood’s How Fiction Works almost four years ago, I was blown away. I’d never heard of free indirect style myself, but the examples and explanations impressed the hell out of me, and not just the ones of f.i.s. The other two books I’ve quoted are similar; they provide different examples, some extra facts; but I think Wood is more convincing, more engaging. Like anyone, I suppose, he has his limitations. I know you’re a fan of post modern literature. Wood is not. He seems to regard it as something like the gothic, a path some writers have taken that really leads nowhere. And, like him or not, it must be admitted that the novel in general has not become Pynchonesque.

Woods has led me to lots of books both old and new. Some of them I haven’t read yet but have definite plans to read: Rameau’s Nephew, Sentimental Education, The Radetzky March, Loving, Sieze the Day, Cristie Malry’s Own Double Entry, The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, The Emigrants, Brick Lane, Too Loud a Solitude. Some of these I just got to faster because of Wood.

~

Posted by Sterling on 16/10/2014, 11:40:28, in reply to “Re: about Emma”

Joffre, I glad that you enjoy those critical works. I like the occasional critical essay myself, but usually I get bored when critical analysis becomes too, well, analytical. I may try the Wood book myself. You have convinced me that it sounds interesting.

I suppose that postmodernist fiction is a somewhat esoteric taste. I’m not surprised that many people do not care for it or respond to it. Based on the books you listed, Wood appears to have a taste for realism leavened with some old-school modernism. Nothing wrong with that. We all have our own taste. It sometimes annoys me, though, when people do not recognize that there can be work of great quality to which they personally do not respond. I just can’t get into Faulkner, for instance, but I don’t insist that Faulkner is an inferior writer. I just don’t care for him. It’s my loss. I don’t like Schumann much either, or chicken.

What I do resist is the idea that influential novels are somehow better. Some of my favorite novels (Tristram Shandy or Moby Dick, for example) are sui generis. They’re not really influential because they are fundamentally unique. Authors who make extreme stylistic choices, like Joyce, Stein, Burroughs, or, yes, Pynchon, wind up exerting a sort of indirect influence. Other writers take from them things that they understand or can use, but the influence is not necessarily obvious. Although a few have tried, no one seems to really be able to pull off Pynchon but Pynchon, but I would submit that he has indeed exerted an influence on the modern novel (as of course the gothic novel has as well.)

~

Posted by Sterling on 13/10/2014, 8:19:45, in reply to “about Emma”

Certainly I agree that there is a difference between what we enjoy and what is greater. For many casual readers, enjoyment is all. If you are only reading for entertainment, the latest thriller or romance or fantasy is likely to hit the spot. This is even true for someone who enjoys the classics, like all of us here at ReadLit. There are classics that I enjoy immensely (Tom Jones), classics that I respect deeply but cannot love (Middlemarch), and classics that I find unreadable (Is Stein’s The Making of Americans a classic?).

In my opinion, what makes one book greater than another is very difficult to define, but I know it has something to do with depth and universality. A remarkable style may be part of what makes a book great, but the hypothesis that the use of a particular stylistic device makes a novel “greater” is… well, let’s just say, I don’t think much of the idea.

~

https://janeausteninvermont.wordpress.com/2015/12/16/the-publishing-history-of-jane-austens-emma/

- Related:

- Book Reviews