Der Kleine Grenzverkehr / Der Kleine Mann – Erich Kästner

Der Kleine Grenzverkehr and Der Kleine Mann – Erich Kästner – 1949/1967

Reviewed by: Claus KREBS P.

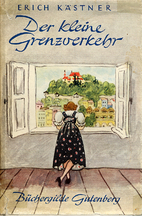

“Der kleine Grenzverkehr” (DkG) and “Der kleine Mann” (DkM) are two entirely different books. In fact, each pertains to a different genre: DkG is a beautiful and funny (as all Kästner books) little love story for adults, and DkM is a lovely and funny little story for children.

Most of Kästner’s books were written for children. However, he hated those silly children’s books like “Pinky and Ponky at the Zoo”. He said that children too know about the good and bad things in life (he had a somewhat difficult childhood himself), so he tried to present not an “ideal” or ridiculous world in his stories, but a world in which people overcome or at least deal with their problems by acting in accordance with high moral values and, most of all, by adopting a humorous approach to life. Humor was essential to Mr. Kästner (I bet he opposed the Nazi regime because of this aspect alone!). His books are full of tender and funny characters and dialogues (this makes them a bit of a challenge, as to adequately translate them).

DkM is, like I said before, a novel for children. DkM means “The little Man”. I read it many years ago, and do not remember the plot exactly, except for the following: It is about a little guy named Max (“Mäxchen”) Pichelsteiner, from the village Pichelstein, where everybody has the same surname, and where nobody grows higher than 30 cm (could be more or less, but they were VERY small). Max is an orphan, since his parents where blown by the wind from the top of the Eiffel tower, during a visit to Paris. He has good friends in the “normal” world, and he is in fact a celebrity (he performs as an outstanding acrobat) but he feels lonely all the same.

DkM is, like I said before, a novel for children. DkM means “The little Man”. I read it many years ago, and do not remember the plot exactly, except for the following: It is about a little guy named Max (“Mäxchen”) Pichelsteiner, from the village Pichelstein, where everybody has the same surname, and where nobody grows higher than 30 cm (could be more or less, but they were VERY small). Max is an orphan, since his parents where blown by the wind from the top of the Eiffel tower, during a visit to Paris. He has good friends in the “normal” world, and he is in fact a celebrity (he performs as an outstanding acrobat) but he feels lonely all the same.

I don’t remember much more than this. I know that there is a sequel to this book. It is called “Der kleine Mann und die kleine Miss”. I guess you do not need a translation to figure out what it is about… The little guy finally is not so lonely any more!

DkG is a love story for adults. I also read it as a child and liked it very much, but it is not really directed to children. “Grenze” means “country border” and “Verkehr” means “traffic”, so the literal translation of the book’s title would be “The little Border-Traffic”. However, it is not at all a story about smugglers! The title has the following explanation (I have the book, so I looked it up again, because it is a little complicated): The main character, Georg Rentmeister, is a German writer who lives in Berlin. It is July 1937 (the book was written back then). He is invited by an Austrian friend to assist to the Salzburg theater festival in August 1937. Hitler had not yet annexed Austria, so both countries still had different policies. Therefore, Austrian law only allowed Germans to travel to Austria with a maximum amount of 10 Marks in their pockets. If they wanted to take more money with them, they had to request a special permit. So Georg writes to the authorities and asks for this permit. The authorities take too long, August arrives, and Georg has to make a choice: either he does not travel at all, or he goes to Austria with only 10 DM in total, or -and this is what he finally chooses- he enters and exits Austria every day, with 10 DM, and sleeps every night at a hotel in the little German town Bad Reichenhall, very near to the border. Now you will understand the title!

DkG is a love story for adults. I also read it as a child and liked it very much, but it is not really directed to children. “Grenze” means “country border” and “Verkehr” means “traffic”, so the literal translation of the book’s title would be “The little Border-Traffic”. However, it is not at all a story about smugglers! The title has the following explanation (I have the book, so I looked it up again, because it is a little complicated): The main character, Georg Rentmeister, is a German writer who lives in Berlin. It is July 1937 (the book was written back then). He is invited by an Austrian friend to assist to the Salzburg theater festival in August 1937. Hitler had not yet annexed Austria, so both countries still had different policies. Therefore, Austrian law only allowed Germans to travel to Austria with a maximum amount of 10 Marks in their pockets. If they wanted to take more money with them, they had to request a special permit. So Georg writes to the authorities and asks for this permit. The authorities take too long, August arrives, and Georg has to make a choice: either he does not travel at all, or he goes to Austria with only 10 DM in total, or -and this is what he finally chooses- he enters and exits Austria every day, with 10 DM, and sleeps every night at a hotel in the little German town Bad Reichenhall, very near to the border. Now you will understand the title!

The book itself is presented in the form of Georg’s diary. It develops into something like a “Lustspiel”, a comedy based on the confusion of identities among the characters: Georg desperately falls in love with an Austrian girl who turns out to be not quite the person he thought she was…

The only “political” aspect of the novel is the mention of the aforesaid restrictions concerning foreign currency. Not a word of Hitler or Germany’s situation can be found in the novel. In fact, it is almost “irresponsibly” uncompromised. It is just a happy and beautiful story. I think that Mr. Kästner wrote it just to escape reality for a while, and to forget about his troubles with the Nazi regime (this, of course, does not affect the quality of the book – it is well written and very entertaining). Nevertheless, in the foreword to the 1948 new edition of the book, Mr. Kästner ironizes a little about the past, and says something like: “As I prepared this little book in 1937, Germany and Austria were considered separate states ‘forever’. When it was published, in 1938, both countries had been united ‘forever’. And the little book had to escape, in order not to be confiscated. Now that the new edition is ready, Germany and Austria are again separated ‘forever’. And the publisher, the author and the illustrator, who once all lived in Berlin, now live in London, Munich and Toronto…”