Moby Dick – Herman Melville – 1851

“We’ll read one chapter each night, and this time we’re going to finish it. All right, here we go. ‘Call me Ishmael …'”

Perry Barlow – The New Yorker

#HowCanWeNotLoveTheNewYorker

Reviewed by: Michael Sympson Date: 3 October 2001

An American Trauma

Reading Moby Dick for the first time should make us realize that English is a real language, and not just a verbal substitute for flag-signals. I know how this must sound for an English speaker – no offence intended. People with a bilingual upbringing, with Russian, German, Spanish, French at the side, know what I mean. It is the gift the mono-lingual is taking for granted. Multilingual people probably can never grasp what it means to completely saturate your temperament and persona in the verbal magic of linguistic perceptions. But they may have traded it for a heightened awareness of the complexity of linguistic interfacing with our world and our ideas.

Even people who introduce themselves as professional writers sometimes complain of what they perceive as Melville’s cloying style, especially in the chapter on the Whale’s whiteness. But there is a lot more in it than “that, although white is frequently considered a good colour, in the case of Moby Dick, it is a bad one, because instead of being reminiscent of purity, it is reminiscent of spectrality on no less than seven and a half pages, including a 469 word sentence.” With all due respect, if cut and dry “message” is all there is to imaginative literature, than it would not be worth bothering about. Forget the lengthy reflections, forget about plot interest, the Anglo-Saxon reader’s favourite obsession, even leave the character cast alone, they are weirdos anyway, every single one of them – Moby Dick is not the kind of book where these things matter.

Instead focus on the intensity of a dream. Accept the exotic symbols of an alien world, as alien as the Planet “Shakespeare.” Accept the warped logic of a nightmare. Yet this is not likely how the product of an American high school education is to respond. Not before somebody points out the similarities between Melville and Kafka. For such reader, literature hasn’t moved an inch since the Vikings had landed at the shores of Newfoundland. But should you feel ready to commit yourselves to Rabelais, then you are ready for Melville, because you have reached the point where opinions are no longer taken seriously. Only the mentally adolescent is opinionated, and literally billions of adolescents crawl this plant’s surface, like lice on a bald midget. Opinions are cheap, everybody can share from his haversack.

However there are things even I rather not see in a book of this nature. Sensitivity, style, rhythm and visualizations are the meat of a poem, great ideas are hogwash. Moby Dick is a prose poem, not an investigative report on the whaling industry. But Melville does not always exactly know where he is going. We know from his letters and messages to Nathaniel Hawthorn, that at times this book had carried away the author. Automatic writing is not exactly my cup of tea, and I suspect, Melville’s absolutely stunning stylistic abilities, cover up a lot of this sort of thing, and I am troubled by Melville’s archaisms. It can be as irritating as in Kipling’s “Kim.” I just can’t see people talk like that, even people of that period. As a biblical flourish, this kind of rhetorics is just preposterous.

So what is going on here? An Einsteinian time dilation between (former) colonials and motherland? Or a case of Shakespearean intoxication? And yet who fails to be charmed by: “Twas rehearsed by thee and me a billion years before this ocean rolled;” (task: design at least two or three alternative and complete cosmologies to fit this sentence) or: “All wars are boyish and are fought by boys, the champions and enthusiasts of the state;” or the almost Virgilian “Charmed circle of everlasting December” that continues to “going through young life’s old routine again;” and notices that “… on the heel of all this … a cluster of dark nods replied” to “bisons with clouds of thunder on his scowling brow” – if that can leave you untouched, go shoot yourself.

If an entire universe can be captured between two book-covers, this is it. A fairy tale, cruel, heroic on the verge of the burlesque, full of hidden gateways to a different matrix in the configuration of things. The whale hunt and Ahab’s hunt for revenge are really the least interesting aspects in this book. But of course one has to know where to look, and I am afraid few are prepared for such examination of the unexpected. Melville was not the type of writer who speaks in bumper stickers nor did he spew fortune cookies (apparently the language of democracy these days.) This accomplishment he left to giggle-peppered sitcoms and squeal-fests with a sprinkle of – what’s the word? – “spirituality,” such as Oprah’s show.

Oh – and “Call me Ishmael” is the most perfect opening sentence of any novel. Nothing ever has surpassed it. Melville gave us the bible of symbolism, but when we try deciphering, we find ourselves confounded by tantalizing signals from deep space – sometimes garbled but always of an overwhelming beauty. This is the word BEFORE the beginning, and before it became flesh.

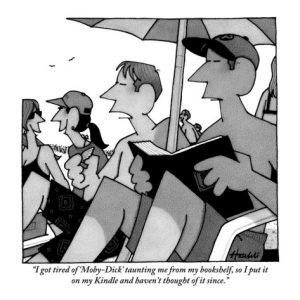

“I got tired of ‘Moby-Dick’ taunting me from my bookshelf, so I put it on my Kindle and haven’t thought of it since.”

William Haefeli – The New Yorker

#HowCanWeNotLoveTheNewYorker