The following is a compilation of discussions and reviews from the previous version of our website. We hope you enjoy these older deliberations. Just beware, there are spoilers in here.

Posted by Lale Eskicioglu, 23/03/2007

The kids have spoken and we should listen to them. When there are so many great works to choose from, why are we forcing this book on our children at schools? To turn them off reading and literature?

Our youth is telling us that they don’t like this book. It is very simple. Why can’t we get the message already? Let’s move onto other books. There are greater ones that are much more interesting and enlightening.

There is this common attitude: ‘Kids don’t like “heavy” books because they lack the education and experience to appreciate them.’ This is the wrong attitude. Kids know of this (our) prejudice, and they feel they have to list their credentials before they can criticize a book. Many students have written (on amazon and elsewhere) that they have read such and such classics and have enjoyed them, before they can say that they didn’t like The Scarlet Letter. They feel they have to tell us that they are good students and that they enjoy reading in general. Most of them say ‘I “got” the book, it is not that I didn’t “understand” it. I understood it and I hated it.’ All of these disclaimers are provided just so that we would take them seriously.

Or they feel they should maybe be modest and self-critical. Some students have declared their lack of intelligence just because they didn’t/couldn’t like this book. (“Maybe I’m dumb, I didn’t like it.”)

None of this should be necessary. Kids don’t like this book and they are not stupid. Let’s choose other books to teach in schools, there are so many good ones.

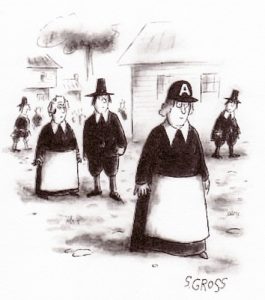

New Yorker cartoonist Sam Gross has a delightful obsession with The Scarlet Letter. Here are a few of his cartoons we could not help sharing:

#HowCanWeNotLoveTheNewYorker #SamGross

A+

Sam Gross

“Why can’t you be more like Hester Prynne? She’s getting straight A’s.”

Sam Gross

How we have tortured our children and wasted the precious time which could have been used to turning them on reading! There are hundreds of one-star and two-star reviews of this book at amazon.com. Here are some excerpts from those reviews:

» I don’t understand why Hester didn’t just pack up Pearl and her stuff, move to another town and tell everyone she was a widow. That would have saved everyone a lot of grief, especially young readers like me.

» This is probably the most painfully boring novel I’ve ever had to suffer through. The characters are annoying, and the plot is uninteresting and overdeveloped.

» The abridged version of this book should read:

“Sin is inevitable. So make the best of bad situations. And oh by the way… women are strong.”

» I teach high school English, and was required to teach this to my students. I don’t know who suffered more, me or them. … Some have labelled this book a tragedy; they are right only in the sense that it is tragically bad.

“Accountant.”

Christopher Weyant, 2002, The New Yorker

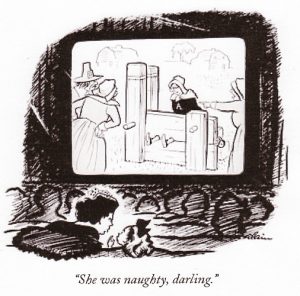

“She was naughty, darling.”

Alain Alain, 1945, The New Yorker

» There is no action, no humour, no joy, only the character study of the puritan society, and a “brave” woman.

» I read this for Honours English … I read all of Jane Austen’s novels by the time I was eleven, and in the summer that I was twelve I read Middlemarch and War and Peace, both of which I loved. That said, it is beyond me why – with so much great literature in the world – the schools think anyone should waste their time on THIS. 150 pages of shame, sin, guilt, evil, and the Scarlet Letter “burning like a red-hot iron.” It is preachy and repetitive the whole way through. Hester might be a decent character if she would stop clinging to her imagined sin, which she seems to enjoy thoroughly. … Also, Hawthorne has a strange obsession with the word ‘ignominy,’ which he uses 8 times in the first 26 pages, 5 times in the last 13 pages, and 4 times in between. It got to the point where, when I came across it, I would say, “Oh, here’s ignominy again.”

» A classic? Hardly. In it’s time this book may have ruffled feathers but these days it’s a struggle to get through. Hawthorne’s writing style is dreary and dreadful; if captivating readers was his aim, he failed miserably.

» Finally, why a whole chapter on a rose bush?

» I didn’t feel like I learned anything from reading this book, the characters are rather flat and the symbols are far too obvious and there is too many of them. It’s like Hawthorne had a contest with himself to see how many symbols he could cram in.

» This completely predictable novel seems more like a beginner’s attempt of writing a book rather than an American classic.

» Throughout this entire book, one part of my brain was in a state of wonder, trying to imagine how anyone could make a book about scandal, sin, adultery, public shame and cowardice so dull. To finish the book was a test of will, and was accomplished because I hate to leave things undone. – There are many fine, engaging, interesting novels, both of our age and of Hawthorne’s. I can’t imagine why one would want to slog through this one.

» In the words of Mr. Hawthorne himself, this book is ignominiously dull.

» It is a travesty that this novel is even classified with the classics. This is by far one of the most boring and pointless novels in existence. The plot dribbles on about sin and adultery with few arguments. The contrasting of light and dark, with shadows, light and colour is overdone and quite childish. Any third grade student can classify purity as light and sin as darkness. More over, there is over a hundred pages of belabouring the point, with no real conclusion.

» Well, I am 15 years old and my english teacher assigned this book for the class. I read only 6 of the chapters and then gave up.

» Buried beneath Hawthorne’s dull insignificant speeches on content that literally has nothing to do with the story, one may be able to find a moral. In saying this, I am referring of course to the 54 page introduction that is almost totally irrelevant to the entire story. He describes everyone that works in the custom house with him and what they wear and eat and do in their spare time, and then in the last 4 or so pages, he talks about the importance of the scarlet letter. What a waste of paper! With all of the trees that he killed writing his intro, you would think that it would actually serve a purpose.

» I’ve bought this book, underlined every hint of symbolism, found all evidence of romanticism, followed every quote involving thematic oppositions, and noted every example of Pearl’s rebellious nature and social alienation, but I cannot find one positive aspect of this novel that makes any of my hard work feel rewarding. The only way this novel could give me a warm feeling is if I place it in a furnace.

» Hawthorne should have stuck to writing non-fictional books about the Puritan settlers.

» Stop pretending this is such an amazing book.

» We had to read this thing for class in 11th grade. It is considered a classic, but I found it really boring and uninteresting.

» So sue me… I just don’t like Nathanial Hawthorne. I think the plot is brilliant, but I find his method of telling the story annoying.

» Yes, I am a 17-year old high school kid. But I can tell good books from the bad ones.

» I hate Hawthorne’s style of writing. It’s over-bloated and self-indulgent. I wish he’d just get to the point and stop blubbering on and on. The plot of the book seems like a modern melodramatic soap opera. All of the characters are one-dimensional. I’m not going to say the book is poorly written, but it’s written in a style that makes the book kind of boring and tedious to read. Overall, a disappointment.

» I’m a 13 year old kid and I just finished reading this book for an English class I am taking. Although it was a very interesting and provocative novel, I did not like it very much. I think it maybe that I’m still too young to thoroughly understand this piece of literature.

» I can’t believe this is still one of the most taught books in high schools across the U.S. With so many terrific classic novels out there by authors like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, why is there still such a focus on this rambling, over-wrought book?

» I’ve read worse. But it takes a lot of mental energy to wade through all the commas and figure out the point of each paragraph. It seems a lot longer than 240 pages. I wouldn’t have read it if I hadn’t been forced to by the school. And the introductory thing is torture.

» Maybe if a couple of generations completely ignore it, it will cease to be a so-called classic.

» For those who still believe that this book is just too sophisticated for all of those dumb high schoolers, let me offer another example. In addition to The Scarlet Letter, my high school English classes also required us to read some other classic works of the English language, and none of these other classics brought about nearly as negative a response as the response brought about by this book. I remember that my classmates and I were by and large much more interested in the tragic story of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Heart of Darkness, Great Expectations, The Lord of the Flies, The Grapes of Wrath and The Great Gatsby were much better reads than The Scarlet Letter ever was. Were these lesser books, because they were more accessible and often faster paced?

~

Colm Tóibín, in his book The Master, assigns Henry James these thoughts with respect to The Scarlet Letter:

![]()

In the days after his father agreed that he could go to law school, Henry discovered Hawthorne. He knew his name, of course, as he knew Emerson and Thoreau, and he had glanced at some of his stories, paying him less attention than the two essayists because of a perceived level of dullness and bareness in the work he had read. They were simple moral tales about simple moral people, light and slight and tenderly trivial. Both Henry and Sargy Perry, with whom Henry discussed these matters, had agreed that literature at its most valuable and rich and intense was written in the countries which Napoleon had reigned over and attacked; literature lay in the places where Roman coins could be found in the soil. Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales reminded him and Perry of just that, tales which could have been told by their aunt about her aunt with all the social detail and sensuous landscape absent.

︙

Henry was thus surprised when Perry spoke with awe of The Scarlet Letter, which he had just finished reading. Perry insisted that Henry must read it immediately, and seemed disappointed a few days later when Henry still had not begun the book. Henry had, in fact, tried the opening pages and found them almost laughably ponderous, and then had been easily distracted by something else and left the novel aside. Now, trying once more, he believed that the semi-comic tone of the opening, with its talk of prisons and cemeteries and sweet moral blossoms, arose from the lack of a proper background, a varied social world. Hawthorne had replaced artistry with solemnity. This was, he thought, a Puritan virtue, of which Henry’s grandfather, he was told, had been in full possession. He did not mind, he told Perry, reading about Puritans, and he did not even mind having ancestors who embodied their virtues, but he did object somewhat to a book in which they and their virtues, if you could really call them that, had seeped into the tone, the very architecture of the work itself.

On Perry’s insistence, he kept the book close to him for several days as he busied himself with Mérimée’s stories, which he was attempting to translate, and a play by Alfred de Musset that had begun to fascinate him. Beside these, the lack of color in Hawthorne’s observations, the thinness of his characters and the slow, wooden tone in which he began did not entice Henry to spend more time with the book. He was thus thoroughly unprepared, when he embarked yet again upon its early pages, for what was to follow.

The book’s assault on his senses did not occur immediately, and even as its spell began to work on him he was unaware that he was being pulled in and held. He could not tell at what moment The Scarlet Letter started to glow and take on the same power as one of the novels by Balzac which he had been reading. At intervals, once he had supped with his family and the night wore on, he put the book down, amazed at how Hawthorne had not bothered himself with the daily, petty meanness of New England, the comic idiosyncrasies of speech or deportment or behaviour. Hawthorne had avoided whimsy; he had eschewed pettiness. He had even kept choice and chance at arm’s length and had gone instead for intensity, taking a single character, a single action, a single place, a single set of beliefs and a single development and surrounding them with a dark and symbolic forest, a great dense place of sin and temptation. Hawthorne had not observed life, Henry thought, as much as imagined it, found a set of symbols and images which would set life in motion. From the very sparseness of the material, from the narrowness and frigidity of the society itself, from the very sense of undeveloped relations and uniform, colourless belief, Hawthorne had taken advantage of what was missing in New England and pressed on with a gnarled and unrelenting vision to create a story that now gripped its reader all through that summer’s night.

![]()

I was all with Henry James (as he is imagined by Colm Toibin) when he thought Hawthorne’s work was

- dull, bare;

- light and slight and tenderly trivial;

- lacking of social detail and sensuous landscape;

- laughably ponderous; and

- his characters were thin, his observations had no colour, his tone was slow and wooden, etc.

When Toibin’s Henry James changed his mind after a while and began to place the book on the same “pulling” level of Balzac’s books, we started to differ. Unfortunately, The Scarlet Letter did not grip this reader as much as it gripped Henry James “all through that summer’s night.”